Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to retrospectively investigate the feasibility and safety of transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of postgastrectomy arterial bleeding.

Methods

Between January 2004 and July 2015, 13,246 patients underwent total or subtotal gastrectomy at our institution, and 24 patients (18 men; mean age 66.8 years; range 42–80 years) underwent transcatheter arterial embolization for postoperative arterial bleeding identified on angiography.

Results

Postgastrectomy arterial bleeding occurred after subtotal gastrectomy in 14 patients (58%) and after total gastrectomy in 10 patients (42%), after a mean of 17 days (range 1–57 days). It manifested itself as luminal bleeding in 10 patients and as abdominal bleeding in 14 patients. Technical success was achieved in all 24 patients (100%). The clinical success rate was 79% (19-24); there were three transcatheter-arterial-embolization–related major complications that resulted in death within 30 days (12%), one case of recurrent bleeding, and one case of persistent bleeding. The cause of death included infarctions in the spleen and/or remnant stomach (n = 2) and bowel perforation (n = 1). The commonest bleeding focus was the gastroduodenal artery (46%, 11 patients), followed by the splenic artery (29%, 7 patients). By surgery type, the gastroduodenal artery was the commonest site of bleeding in subtotal gastrectomy (64%, 9/14) and the splenic artery was commonest site of bleeding in total gastrectomy (50%, 5/10).

Conclusions

Transcatheter arterial embolization demonstrated high technical and clinical success rates with an acceptable complication rate in the management of postgastrectomy arterial bleeding. However, transcatheter arterial embolization may not be the best treatment option in patients who have undergone subtotal gastrectomy and bled from the splenic artery owing to the high risk of infarctions of the remnant stomach and the spleen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The postoperative complication rate of radical gastrectomy is reported to range from 9.8% to 24.5%, and has been decreasing with advances in surgical techniques and perioperative patient care [1–5]. The major complications include abdominal infection, hemorrhage, anastomosis or stump leakage, and pancreatitis. Of these, the incidence of postgastrectomy bleeding is reported to be 0.6–4% [1–5], and its clinical manifestations differ widely. In particular, arterial or pseudoaneurysmal bleeding after gastrectomy is a rare but rapidly progressing and potentially life-threatening event [6, 7].

The management of postgastrectomy bleeding includes medical treatments such as hydration and transfusion, endoscopic and radiologic procedures, and reoperation. In general, medical and endoscopic treatments are useful for luminal bleeding in hemodynamically stable patients, whereas radiologic treatment and reoperation are preferred in abdominal bleeding that is mostly accompanied by hemodynamic instability [6, 7].

In recent years, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) has emerged as an effective and safe diagnostic and treatment modality for postoperative ruptured or unruptured pseudoaneurysm of the visceral artery [8, 9]. In earlier studies, postoperative arterial bleeding after gastrectomy was successfully managed by means of TAE in some patients. However, owing to the rarity of postgastrectomy arterial bleeding (PAB), between 1 and 14 patients treated with TAE were included in the studies [1, 6, 7], and the efficacy and safety of TAE need to be documented in a larger patient cohort.

This study aimed to retrospectively investigate the feasibility and safety of TAE in the management of PAB.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board; informed consent was waived owing to its retrospective nature. The patient data used for this study were obtained from electronic medical records and the picture archiving and communication system. From January 2004 to July 2015, 13,246 patients underwent total gastrectomy (TG) or subtotal gastrectomy (STG) at our institution. Among them, 24 patients underwent TAE for PAB identified on angiography. The indications for TAE were as follows: (1) clinically suspicious intra-abdominal bleeding; (2) patients with postoperative bleeding who are not amenable to endoscopic treatment because of hemodynamic instability; (3) massive bleeding that is uncontrollable by endoscopic hemostasis; (4) massive bleeding that impedes the localization of the bleeding site; (5) endoscopic inaccessibility to the bleeding site because of surgical alteration; (6) recurrent bleeding after endoscopic hemostasis.

Postgastrectomy bleeding

We adopted the definition of postoperative bleeding from the study by Park et al. [6]. Postoperative bleeding was defined as a sudden drop in the hemoglobin level of more than 2 g/dL in 24 h, and the presence of signs of bleeding, which were divided into two categories: luminal bleeding and abdominal bleeding. Luminal bleeding was characterized by hematochezia, melena, hematemesis, or bleeding through the nasogastric tube. Abdominal bleeding was diagnosed when there was bleeding from the abdominal drain, or abdominal distention with radiologic findings. We classified the bleeding episode into two groups according to the onset: early for bleeding events that occurred between day 1 and day 6, and delayed for those that occurred from postoperative day 7.

Surgical procedures

All patients in this study underwent TG or STG in conjunction with D1 or higher lymph node dissection based on the recommendation of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Carcinoma [10]. TG with spleen-preserving lymphadenectomy and esophagojejunostomy was performed for proximal gastric cancer. Combined resection of the spleen or the distal part of the pancreas was considered for direct invasion or metastatic lymphadenopathy around the splenic hilum. For distal gastric cancer, STG with either Billroth I (gastroduodenostomy) or Billroth II (gastrojejunostomy) reconstruction was performed.

Embolization procedures

An endovascular procedure was performed by four experienced interventional radiologists. Before each procedure, computed tomography (CT) images and endoscopic findings, if available, were thoroughly reviewed to locate the source of bleeding. The right common femoral artery was punctured under ultrasound guidance, whenever possible. A 5-F vascular access sheath was inserted into the right common femoral artery. A 0.035-in. hydrophilic guide wire (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and a 5-F angiographic catheter (RH catheter or RHR catheter, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) were used in celiac artery and/or superior mesenteric artery (SMA) angiography.

If celiac or SMA angiography revealed extravasation of contrast media and/or a pseudoaneurysm, a microcatheter was coaxially advanced for further selective angiography and embolization. For embolization, various materials, including absorbable gelfoam sponge (SPONGOSTAN, Ferrosan Medical Devices, Søborg, Denmark), N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue (Histoacryl, B. Braun Melsungen, Melsungen, Germany), and microcoils (Tornado or Micronestor, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA; or Interlock, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) were used according to the severity of bleeding, hemodynamic status, anatomic accessibility, and surgeon preferences. As the NBCA glue tends to travel more distally with a lower ratio, it was mixed with Lipiodol (Andre Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France) at different ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:5, depending on the distance between the target vessel and the tip of the microcatheter and on the surgeon’s experience. Gelfoam sponge was manually cut into tiny pledgets. After embolization, repeated angiography with a 5-F catheter was performed to ensure that the offending arteries were completely occluded (Fig. 1).

A 57-year-old female patient developed a sudden onset of hematochezia and hemodynamic instability 17 days after subtotal gastrectomy. Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) scans showing a fluid collection with multiple air densities (arrow), suggestive of leakage from the duodenal stump, and b a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) from the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) stump. c Celiac angiogram demonstrating a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) from the GDA stump. d The GDA stump was cannulated with a 2.2-F microcatheter, and embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue was performed. e Completion angiogram showing the completely occluded bleeding focus. f One-month follow-up contrast-enhanced CT scan showing the resolution of the fluid collection and glue casting of the GDA stump from the previous transcatheter arterial embolization

Definitions and analysis

Coagulopathy was defined as an international normalized ratio of more than 1.5 or a platelet count of less than 80,000/µL [11–13]. The angiographic findings were classified as (1) active bleeding or (2) pseudoaneurysm. On angiography, active bleeding was defined as visible extravasation of the contrast medium, and pseudoaneurysm was defined as abnormal localized collection of the contrast medium in and around the hematoma. Technical success was based on the immediate angiographic findings, and was defined as the complete exclusion of the bleeding artery. Clinical success was defined as the absence of the following for 30 days after the initial embolization: recurrent bleeding, persistent hemorrhage resulting in death within 30 days, or embolization-related complications. Complications were classified as either major or minor according to the guidelines of the Society of Interventional Radiology Standards of Practice Committee. Patient survival was defined from the time between the TAE and a patient’s death or the last available follow-up examination. To evaluate the efficacy of TAE for PAB, comparisons between the mean hemoglobin levels during the 3 days before and after the procedure were performed. The mean hemoglobin level before and after TAE was compared by use of the paired t test, and the clinical failure rate for the offending artery was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Overall results

During the period from January 2004 to July 2015, 24 patients underwent TAE for PAB. These patients comprised 18 men and 6 women with a mean age of 66.8 years (range 42–80 years). The patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. PAB occurred after STG in 14 patients and after TG in 10 patients, after a mean of 17 days (range 1–57 days). There were 10 cases of luminal bleeding and 14 cases of abdominal bleeding. At the time of bleeding, the mean hemoglobin level was 8.1 ± 1.9 g/dL, and the mean hemoglobin level change from before to during the bleeding episode was 3.8 ± 2.1 g/dL. The mean hemoglobin level 3 days after TAE was 9.7 ± 1.6 g/dL. The change in the mean hemoglobin level measured before and after embolization was significant (p < 0.05). Combined organ resection was performed in three patients (12%). The embolic materials used for TAE included NBCA glue (n = 12), microcoils (n = 6), a combination of microcoils and NBCA glue (n = 4), and Gelfoam slurry (n = 2).

Technical and clinical outcomes

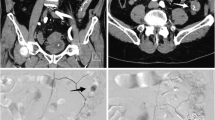

Technical success was achieved in all 24 patients (100%). The clinical success rate was 79% (19 of 24 patients), with three TAE-related major complications that resulted in death within 30 days (12%), one case of recurrent bleeding from the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) that required repeated TAE, and one case of persistent bleeding from the splenic artery after TAE that required surgical splenectomy. Of the three major complications, infarctions of the remnant stomach and spleen occurred after TAE for bleeding from the splenic artery in two patients who underwent STG (Fig. 2). Both of these patients underwent aggressive conservative treatment but died of septic shock. In the remaining patient, the infarction and perforation occurred after the TAE for bleeding from the middle colic artery. Despite subtotal colectomy and ileostomy creation, the patient died of sepsis. The clinical failure rate of TAE for the splenic artery origin was significantly higher than that of the non-splenic artery origin (p = 0.014). The clinical courses of the 24 patients who underwent TAE for PAB are summarized in Fig. 3.

An 80-year-old male patient developed a sudden onset of hematemesis and bleeding through the nasogastric tube 9 days after subtotal gastrectomy. a Celiac angiogram showing active contrast medium extravasation (arrow) from the splenic artery. b The bleeding focus was embolized by use of microcoils and N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue. c, d Follow-up computed tomography scans showing fluid collection (arrow) along the pancreas, and extensive infarctions of the remnant stomach (S) and the spleen (SP). This patient died of sepsis

Offending arteries by surgery type (STG vs TG)

The detailed distribution of arterial bleeding foci is summarized in Table 2. The most commonly affected artery was the GDA (46%, 11 patients), followed by the splenic artery (29%, 7 patients), the middle colic artery (8.3%, 2 patients), the inferior phrenic artery (8.3%, 2 patients), the left gastric artery (4%, 1 patient), the left hepatic artery (4%, 1 patient), and the jejunal artery (4%, 1 patient). In one patient, both the splenic artery and the left hepatic artery were the bleeding foci. By surgery type, the GDA was the commonest site of bleeding in STG (n = 9) and the splenic artery was the commonest site of bleeding in TG (n = 5).

Clinical presentation of postgastrectomy bleeding

PAB was characterized by an acute-onset, hemodynamic instability, and massive bleeding, and its clinical manifestations are summarized in Table 3. In two patients (8%), bleeding occurred in the early period after gastrectomy and presented as abdominal bleeding: abdominal distention (n = 1) and sudden drop in blood pressure with positive CT findings for bleeding (n = 1). Four patients (17%) developed bleeding in the late period (2–6 days after surgery; mean 3.8 days; range 2–5 days) and it manifested itself as abdominal bleeding: bleeding from the drainage tube (n = 2) and abdominal distention (n = 2).

Eighteen of the 24 patients (75%) experienced bleeding in the delayed period (after the seventh day from surgery; mean 21 days; range 7–57 days). Bleeding manifested itself as luminal bleeding (n = 11) and abdominal bleeding (n = 7); hematochezia, melena, hematemesis, or bleeding from the nasogastric tube (n = 11); bleeding from the drainage tube and CT findings suggestive of bleeding (n = 7). Anastomosis leakage (n = 7), duodenal stump leakage (n = 5), and abdominal abscess (n = 3) were also observed.

Before TAE, three-phase dynamic CT scans were performed in 18 patients (75%). CT revealed hemoperitoneum in all 18 patients, and direct CT findings of bleeding were present in 16 patients: active contrast medium extravasation (n = 10) and pseudoaneurysm (n = 7).

Discussion

Postgastrectomy bleeding is a rare but life-threatening complication, and arterial bleeding is particularly important because it entails a high mortality [6, 7]. To manage postgastrectomy bleeding, diverse treatment modalities have been used. Most PAB cases present as sudden massive bleeding with hemodynamic instability in the delayed period, and reoperation on the offending artery could be technically challenging, with a high mortality rate, owing to the anatomic inaccessibility caused by adhesion and poor localization of the bleeding source. Endoscopic hemostasis is considered as the treatment of choice for luminal bleeding, but there are some limitations such as poor localization of the bleeding site due to massive bleeding and not being able to reach the bleeding site because of surgical alteration. Owing to advances in procedural techniques and embolic materials, TAE has gained popularity as an effective, stand-alone treatment modality for diverse arterial bleeding [14–17]. In a similar vein, we assume that TAE can serve as the mainstay treatment for postoperative arterial bleeding. This study demonstrates that TAE is a safe and effective treatment option for PAB. In the present study, the technical and clinical success rates were 100% and 79% respectively. There were three major TAE-related complications that resulted in death within 30 days. Recurrent and persistent bleeding episodes after TAE were reported in two patients.

Of the 24 PABs, 8% occurred in the early period, and it is assumed that the bleeding was due to direct injury to the perigastric arteries and insufficient hemostasis during surgical manipulation. However, most PABs (92%) occurred in the late or delayed period, and it was notable that coexisting postoperative complications, including leakage from the anastomosis or duodenal stump and abdominal abscess, were present in 75% of those patients. This seems to be in agreement with the observation of delayed presentation of arterial pseudoaneurysmal bleeding in patients following radical gastrectomy [1, 6, 7]. The longer interval between surgery and arterial bleeding might involve the following mechanisms: (1) the adventitia of vessels, often removed en bloc with perigastric lymph nodes, a process called “vascular skeletonization,” may render the vessels more vulnerable; (2) exposure of the perigastric arteries to the enteric, pancreatic, and/or biliary juices from anastomotic or stump leakage. Therefore, drainage of anastomotic leakage, bile, or pancreatic juice after gastrectomy is important in preventing pseudoaneurysm formation.

Overall, the GDA was the commonest focus of bleeding in this study. Our results differ from those of the study by Park et al. [6], probably because of our inclusion of only patients treated by TAE (i.e., a defined subset of patients with postoperative hemorrhage). A further possible explanation stems from the association of leakage from the anastomosis or duodenal stump and abdominal abscess in our late-presenting cohort of cases. By surgery type, the GDA was the commonest source of bleeding in STG and the splenic artery was the commonest source of bleeding in TG. In STG, a gastroduodenostomy or gastrojejunostomy is created, and the GDA is ligated and left as a stump. Inadvertent surgical ligation or exposure of the GDA stump to the erosive fluid from anastomosis or duodenal stump leakage could explain the high incidence of the GDA as a bleeding site. In TG, the splenic artery was the commonest bleeding focus. At our institution, D1 plus β or D2 dissection is routinely performed in TG. Lymph node dissection (11p and 11d nodal stations according to the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Carcinoma [10]) along the splenic artery can cause thermal or mechanical damage to the splenic artery because those lymph nodes lie deep behind the pancreas. Furthermore, exposure to the intra-abdominal abscess or leakage adjacent to the splenic artery could be another reason.

Death following TAE occurred in three patients (12.5%), and sepsis was the cause in all cases. Two patients had undergone STG, and had splenic artery bleeding. In one patient, following complete embolization of the splenic artery, there was infarction of both the remnant stomach and the spleen, causing sepsis and death within 30 days. In the second patient, only splenic infarction was documented, but sepsis also occurred. Of course, with STG, perfusion of the remnant stomach through the short gastric arteries is vital, and complete embolization of the main splenic trunk can significantly compromise blood supply. This theory is further supported by a case reported by Hajime et al. [18] in which gastric remnant necrosis occurred in a patient who underwent STG. Therefore, TAE may not be the best option for patients who have undergone STG and bled from the splenic artery. Instead, if technically feasible, the placement of a stent graft in the splenic artery would not only treat bleeding but would also salvage the spleen and/or the remnant stomach. If TAE is inevitably required in such patients, further resection of the remnant stomach and the spleen should also be considered immediately after the procedure to avoid infarction-related sepsis.

In this study, 18 patients underwent pre-TAE CT scans, and positive CT findings of bleeding were seen in 16 patients (89%). This suggests that when postoperative arterial bleeding after radical gastrectomy is suspected, CT can be used to confirm the bleeding and to locate the bleeding site. In particular, if the patient had undergone STG and bleeding from the splenic artery was detected on CT, TAE should be avoided and another treatment modality, such as stent graft placement or repeated laparotomy, should be considered.

In the third patient, the middle colic artery was compromised even though the embolization was performed in a super-selective fashion. In this case, we believe the NBCA glue regurgitated behind the tip of the microcatheter, leading to embolization of a broader area than planned, with infarction and perforation of the transverse colon. Subsequent subtotal colectomy failed to save the patient, who died of sepsis. Although fatal complications were observed after embolization with NBCA glue in this series, TAE by use of glue with or without other embolic materials for gastrointestinal bleeding has recently been advocated by several investigators [15, 19, 20]. Although the use of NBCA glue as an embolic material requires sufficient training for the interventional radiologist, to minimize the potential complications, this material offers some theoretical advantages as a primary embolic agent for PAB. Whereas microcoils are deployed proximally to the tip of a catheter, NBCA glue can travel more distally than the tip of the microcatheter and can make possible the embolization of a bleeding artery distal to the point that a microcatheter cannot reach because of the small luminal caliber, tortuosity, or spasm of the artery to be occluded. Another advantage is that NBCA glue can polymerize even in coagulopathic conditions. In this series, most patients had intra-abdominal infection or leakage, and seven patients (30%) had coagulopathy. This was probably because intra-abdominal infection would quickly consume coagulation factors, making those patients coagulopathic [21]. Therefore, NBCA glue is presumed to be more effective for TAE in patients with PAB.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective design, the small number of patients, and the lack of a control group. However, because PAB is a rare and emergent condition, it is difficult to collect enough cases at a single center and perform a prospective, comparative study with a control group treated with other treatment modalities.

In conclusion, TAE demonstrated 100% technical success and acceptable 30-day mortality (12.5%) in the high-risk setting of septic patients with PAB. However, TAE in patients following STG who bleed from the splenic artery risks infarction of the remnant stomach and spleen. Sequential surgical resection and reconstruction may be required in this setting.

References

Jeong O, Park YK, Ryu SY, Kim DY, Kim HK, Jeong MR. Predisposing factors and management of postoperative bleeding after radical gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Surg Today. 2011;41(3):363–8. doi:10.1007/s00595-010-4284-2.

Kim MC, Kim W, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Ryu SY, Song KY, et al. Risk factors associated with complication following laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale korean multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2692–700. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-0075-z.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245(1):68–72. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000225364.03133.f8.

Kodera Y, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Sano T, Nashimoto A, Kurita A. Identification of risk factors for the development of complications following extended and superextended lymphadenectomies for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92(9):1103–9. doi:10.1002/bjs.4979.

Ryu KW, Kim YW, Lee JH, Nam BH, Kook MC, Choi IJ, et al. Surgical complications and the risk factors of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(6):1625–31. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-9845-x.

Park JY, Kim YW, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Lee JH, Ryu KW, et al. Unique patterns and proper management of postgastrectomy bleeding in patients with gastric cancer. Surgery. 2014;155(6):1023–9. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.01.014.

Song W, Yuan Y, Peng J, Chen J, Han F, Cai S, et al. The delayed massive hemorrhage after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer: characteristics, management opinions and risk factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(10):1299–306. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.020.

Lee JH, Hwang DW, Lee SY, Hwang JW, Song DK, Gwon DI, et al. Clinical features and management of pseudoaneurysmal bleeding after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am Surg. 2012;78(3):309–17.

Tsai CC, Chiu KC, Mo LR, Jao YT, Lin YW, Yang TM, et al. Transcatheter arterial coil embolization of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms after hepatobiliary and pancreatic interventions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(73):41–6.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma—2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1(1):10–24. doi:10.1007/s101209800016.

O’Connor SD, Taylor AJ, Williams EC, Winter TC. Coagulation concepts update. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(6):1656–64. doi:10.2214/ajr.08.2191.

Patel IJ, Davidson JC, Nikolic B, Salazar GM, Schwartzberg MS, Walker TG, et al. Consensus guidelines for periprocedural management of coagulation status and hemostasis risk in percutaneous image-guided interventions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(6):727–36. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2012.02.012.

Shander A, Goodnough LT. Update on transfusion medicine. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(9 Pt 2):57s–68s. doi:10.1592/phco.27.9part2.57S.

Hur S, Jae HJ, Lee M, Kim HC, Chung JW. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a single-center experience with 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(1):10–9. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2013.09.012.

Koo HJ, Shin JH, Kim HJ, Kim J, Yoon HK, Ko GY, et al. Clinical outcome of transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for control of acute gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(3):662–8. doi:10.2214/ajr.14.12683.

Park HJ, Shin JH, Han KC, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Sung KB. Transcatheter arterial embolization of angiographically visible and occult renal capsular artery hemorrhage in 28 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(7):973–80. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2016.03.024.

Zhou CG, Shi HB, Liu S, Yang ZQ, Zhao LB, Xia JG, et al. Transarterial embolization for massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage following abdominal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(40):6869–75. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6869.

Hajime I, Akihito E, Hiroharu N, Masataka H, Hiroki M, Junzo Y. Gastric remnant necrosis following splenic infarction after distal gastrectomy in a gastric cancer patient. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(7):583–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.03.034.

Huang YS, Chang CC, Liou JM, Jaw FS, Liu KL. Transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in hemodynamically unstable patients: results and predictors of clinical outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(12):1850–7. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.08.005.

Loffroy R. Which acrylic glue should be used for transcatheter arterial embolization of acute gastrointestinal tract bleeding? Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(4):W465. doi:10.2214/ajr.15.14874.

Ren J, Zhao Y, Yuan Y, Han G, Li W, Huang Q, et al. Complement depletion deteriorates clinical outcomes of severe abdominal sepsis: a conspirator of infection and coagulopathy in crime? PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047095.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Additional information

K. Han and B. M. Ahmed contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, K., Ahmed, B.M., Kim, MD. et al. Clinical outcome of transarterial embolization for postgastrectomy arterial bleeding. Gastric Cancer 20, 887–894 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0700-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0700-2