Abstract

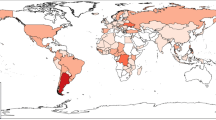

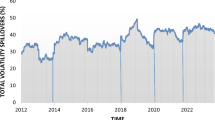

This paper examines whether the pricing of risk is important for macroeconomic activity at the country level. We design a risk-adjusted yield spread and test its predictive content for economic activity on the periphery and the centre of Europe over the 1990–2012 period. This risk-adjusted bond yield spread is defined in a cross-country context and referred to as the GZ-type spread. Increases in the yield on corporate bonds issued in the countries on the periphery relative to the riskless yield (calculated using German zero-coupon term structure data) reflect increases in the risk premium that the financial market imposes on borrowers. The risk premium rises in all countries during European-wide recessions of the recent past, particularly those associated with the Global Financial and the Sovereign Debt Crisis. Our findings indicate further that this GZ-type spread acts as a reliable signal for imminent and near-term economic activity in countries where financial markets were shaken to their foundations during the Crisis period. For Germany, the GZ-spread has predictive content for industrial production but not for the unemployment rate. For GDP its predictive ability is confined to the EMU period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Wall Street Journal, “Bonds with Banks Fraying,” April 10 (2012).

Ibid.

Financial Times, “European Company Borrowing Costs Rise,” November 30, (2010). The article reports that “the last bond issue from a company domiciled in Spain, Portugal or Ireland came from Iberdrola, the Spanish utility, on October 6th.” Thus no corporate bond placement was effected in almost 2 months.

Financial Times, “Loan Rates Point to Eurozone Fractures,” September 3, (2012). The rates quoted are the average rate on loans to non-financial corporations, 1–5 years, up to €1 million in value.

Ibid.

Ideally, we would have included Greece in our examination. Unfortunately, data constraints made this impossible. Germany is chosen to be the centre on account of it having the largest economy in Europe and its triple A credit rating.

On this see Committee on the Global Financial System, CGFS Papers, No 43, (2011). This report covers events only up to 2010. Neri and Ropele (2014) investigate the link between tensions in sovereign debt markets and credit conditions in the Euro area, particularly the banking sector of individual countries during the Sovereign Debt Crisis.

There has been a long-standing interest in the predictive ability of various financial indicators for economic activity and inflation. Among the most frequently used proxies for monetary conditions are the yield spread on long-term and short-term government bonds (Bernanke 1990; Harvey 1988; Estrella and Hardouvelis 1991; and others) and the risk spread, defined as the difference between the yield on short-term commercial paper and the yield on Treasury Bills of the same maturity (Friedman and Kuttner 1992; Emery 1996). Moersch (1996) finds that money market spreads predict output better than other spreads along the yield curve. Various US bond yield spreads (long-term, high yield) figure prominently in Gertler and Lown (1999), Mody and Taylor (2004) and King et al (2007). De Bondt (2004) analyses bond yield spreads in Europe. More recent contributions such as Mueller (2009) also examine corporate bond yield spreads defined along rating categories in the context of a macro-finance term structure model of the type proposed by Ang et al. (2006). A comprehensive survey of the literature on the role of asset prices in forecasting economic activity is by Stock and Watson (2003).

Bleaney et al. (2012) compose country-specific GZ-spreads in the spirit of Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012) for a number of European countries. Their analysis of the predictive content of credit spreads differs from ours in three important respects. They are: construction of the GZ-spread, countries included in the study, and estimation method. According to the findings of their panel data study, the GZ-spread is a reliable predictor of future economic activity in Europe.

The extraction of the excess bond premium requires firm-specific data which the authors do not have. It would no doubt be interesting to ascertain whether, as in Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012), the excess bond premium accounts for most of the forecasting success of the GZ-spread.

Since this spread is calculated in a cross-country context, the measured spread consists of a combination of two components. One measures corporate credit risk while the other reflects peripheral country risk.

Our study focuses squarely on the bond market and its participants. Access to the bond market is typically restricted to large and fairly well known companies. Smaller and lesser known companies are forced to rely on bank loans to finance their working capital needs. As larger firms have greater flexibility in sourcing finance on the open market or from banks than smaller firms, the latter suffer disproportionately more from a tightening of monetary policy or during times of financial turmoil. One could thus plausibly argue that a bond market credit spread is a conservative indicator of general financial market conditions.

The maturity profile of corporate bonds included in the sample corresponds broadly to that reported by the European Central Bank in its February 2012 Bulletin. Over the 1999–2007 period the average maturity of corporate bonds was shortest in Germany at 4.7 years and highest in Ireland at 8.8 years.

Strictly speaking, January 1, 1999 marks the beginning of the third stage of the Economic and Monetary Union. On this date the Euro officially replaced the Ecu as the official currency of the union. For the first three years the Euro served only as a unit of account. Euro coins and banknotes were not introduced until January 1, 2002.

For Germany one also observes a steep increase in the GZ-spread in 1998 around the time of the Russian Default.

The first recession preceded Black Wednesday in September 1992 when the European Exchange Rate Mechanism came under attack. The second recession was triggered off by the Global Financial Crisis while the third came upon the heels of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis.

The estimated coefficient on the relative inflation differential is reported only if it is statistically significant.

The sample period for quarterly observations of real GDP in Ireland begins only in 1997.

The results reported in Table 7 for the 1998:2–2011:12 period in Ireland are very similar to those obtained for the slightly shorter EMU period. Hence the latter are not reported.

For Portugal, the standard errors of the coefficient estimates on the first differences of GZ and GZ*DUM are highly inflated due to severe multicollinearity. The correlation coefficient for the two regressors is 0.95. A similar problem, though less serious, applies to the standard errors estimated for Germany. The correlation coefficient for GZ and GZ*DUM is 0.80 for Germany.

Downgrades of sovereigns typically lead to downgrades of banks or non-financial corporations as the rating of a sovereign acts as a ceiling for the rating of the latter. See the CGFS Paper No. 43, 2011 for a detailed account of the effect of sovereign credit risk on bank funding conditions.

For Ireland data on corporate borrowing has been published by the ECB only since 2010. Italy’s corporate bond market is relatively more developed and more important as a source of corporate borrowing than Spain’s or Portugal’s. In 2009, new corporate borrowing in Italy amounted to approx. €15 billion while in Spain and Portugal it was <€4 billion. In 2011 issuance of new corporate bonds plunged to €6.9 billion in Italy, €1 billion in Spain, and €1.5 billion in Portugal.

In 2012 the situation in the corporate bond markets in Italy, Portugal, and Spain began to ease. Corporate borrowing increased substantially in all three countries but its effect on economic activity cannot be investigated as the sample period ends in 2012.

References

Ang A, Piazzesi M, Wei M (2006) What does the yield curve tell us about GDP growth? J Econom 131:359–403

Bernanke BS (1990) On the predictive power of interest rates and interest rate spreads. N Engl Econ Rev 51–68

Bernanke B, Gertler M (1995) Inside the black-box—the credit channel of monetary-policy transmission. J Econ Persp 9:27–48

Bernanke B, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1996) The financial accelerator and the flight to quality. Rev Econ Stat 78:1–15

Bernanke B, Gertler M, Gilchrist S (1999) The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. Handbook of macroeconomics, vol 1C. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1341–1393

Bleaney M, Mizen P, Veleanu P (2012) Credit spreads as predictors of economic activity in eight European economies. University of Nottingham, Mimeo

Committee on the Global Financial System (2011) The impact of sovereign credit risk on bank funding conditions. In: CFGS Papers, No 43. Bank for International Settlements

De Marco F (2015) Bank lending and the sovereign debt crisis, mimeo

De Bondt G (2004) The balance sheet channel of monetary policy: first empirical evidence for the euro area corporate bond market. Int J Fin Econ 9:219–228

Emery KM (1996) The information content of the paper-bill spread. J Econ Bus 48:1–10

Estrella A, Hardouvelis G (1991) The term structure as a predictor of real economic activity. J Fin 46:555–576

Financial Times European Company Borrowing Costs Rise. November 30, 2010

Financial Times Loan Rates Point to Eurozone Fractures. September 3, 2012

Friedman B, Kuttner K (1992) Money, income, prices, and interest rates. Am Econ Rev 82:472–492

Gertler M, Lown CS (1999) The information in the high-yield bond spread for the business cycle: evidence and some implications. Oxf Rev Econ Pol 15:132–150

Gilchrist S, Zakrajšek E (2012) Credit spreads and business cycle fluctuations. Am Econ Rev 102:1692–1720

Harvey CR (1988) The real term structure and consumption growth. J Fin Econ 22:305–322

Hubbard G (1995) Is there a “credit channel” for monetary policy. Review 77:63–77

Kaya O, Meyer T (2013) Corporate bond issuance in Europe. EU Monitor, Deutsche Bank Research, January 31st

King TB, Levin AT, Perli R (2007) Financial market perceptions of recession risks. Fin and Econ Disc Series 2007-57, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Mody A, Taylor MP (2004) Financial predictors of real activity and the financial accelerator. Econ Lett 82:167–172

Moersch M (1996) Predicting output with a money market spread. J Econ Bus 2:185–200

Mueller P (2009) Credit spreads and real activity. London School of Economics, Mimeo

Neri S, Ropele T (2014) The macroeconomic effects of the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area. Mimeo

Stock JH, Watson MW (2003) Forecasting output and inflation: the role of asset prices. J Econ Lit 41:788–829

Wall Street Journal Bonds with Banks Fraying. April 10, 2012

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions. We also wish to thank Richard Froyen, Alexander Jung, Philip Meguire, Mathias Moersch and seminar participants at the University of Antwerp and Freie Universitaet Berlin for feedback and constructive comments. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors alone and should not be interpreted as the views of NZ Treasury.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guender, A., Tolan, B. The predictive ability of a risk-adjusted yield spread for economic activity in Europe. Empirica 44, 1–27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-015-9309-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-015-9309-z