Abstract

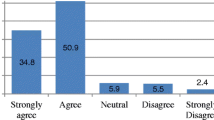

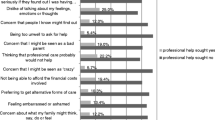

Objective To measure stigma associated with four types of postpartum depression therapies and to estimate the association between stigma and the acceptance of these therapies for black and white postpartum mothers. Methods Using data from two postpartum depression randomized trials, this study included 481 black and white women who gave birth in a large urban hospital and answered a series of questions at 6-months postpartum. Survey items included socio demographic and clinical factors, attitudes about postpartum depression therapies and stigma. The associations between race, stigma, and treatment acceptability were examined using bivariate and multivariate analyses. Results Black postpartum mothers were less likely than whites to accept prescription medication (64 vs. 81%, p = 0.0001) and mental health counseling (87 vs. 93%, p = 0.001) and more likely to accept spiritual counseling (70 vs. 52%, p = 0.0002). Women who endorsed stigma about receipt of postpartum depression therapies versus those who did not were less likely to accept prescription medication, mental health and spiritual counseling for postpartum depression. Overall black mothers were less likely to report stigma associated with postpartum depression therapies. In adjusted models, black women versus white women remained less likely to accept prescription medication for postpartum depression (OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.24–0.72) and stigma did not explain this difference. Conclusions Although treatment stigma is associated with lower postpartum depression treatment acceptance, stigma does not explain the lower levels of postpartum depression treatment acceptance among black women. More research is needed to understand treatment barriers for postpartum depression, especially among black women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abrams, L. S., Dornig, K., & Curran, L. (2009). Barriers to service use for postpartum depression symptoms among low-income ethnic minority mothers in the United States. Qualitative health research, 19(4), 535–551.

Amankwaa, L. C. (2003). Postpartum depression among African–American women. Issues Mental Health Nursing., 24(3), 297–316.

Blank, M. B., Mahmood, M., Fox, J. C., & Guterbock, T. (2002). Alternative mental health services: the role of the black church in the South. American Journal of public health, 92(10), 1668–1672.

Boyd RC, Le HN, Somberg R. Review of screening instruments for postpartum depression. Archives Womens Mental Health. 2005;8(3):141–153.

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., et al. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27.

Cooper, L. A., Gonzales, J. J., Gallo, J. J., et al. (2003). The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care, 41(4), 479–489.

Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA.(2014) The Impact of Mental Illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science Public Interest. 15(2):37–70.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150, 782–786.

Dennis, C. L., & Chung-Lee, L. (2006). Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.), 33(4), 323–331.

Edwards E, Timmons S. (2005) A qualitative study of stigma among women suffering postnatal illness. Journal of Mental Health. 14(5):471–481.

Gaynes, B. N., Gavin, N., Meltzer-Brody, S., et al. (2005) Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 119:1–8.

Givens JL, Katz IR, Bellamy S, Holmes WC.(2007) Stigma and the acceptability of depression treatments among african americans and whites. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 22(9):1292–1297.

Gjerdingen, D. K., & Yawn, B. P. (2007). Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. Journal of American Board of Family Medicine. 20(3), 280–288.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Goodman, S. H., Dimidjian, S., & Williams, K. G. (2013). Pregnant African American women’s attitudes toward perinatal depression prevention. Cultural diversity & ethnic minority psychology, 19(1), 50–57.

Hanusa, B. H., Scholle, S. H., Haskett, R. F., Spadaro, K., & Wisner, K. L. (2008). Screening for depression in the postpartum period: A comparison of three instruments. Journal of women’s health (2002), 17(4), 585–596.

Howell, E. A., Balbierz, A., Wang, J., Parides, M., Zlotnick, C., & Leventhal, H. (2012). Reducing postpartum depressive symptoms among black and Latina mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology, 119(5), 942–949.

Howell, E. A., Bodnar-Deren, S., Balbierz, A., et al. (2014). An intervention to reduce postpartum depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 17(1), 57–63.

Howell, E. A., Bodnar-Deren, S., Balbierz, A., Parides, M., & Bickell, N. (2014). An intervention to extend breastfeeding among black and Latina mothers after delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 239(3), e231–e235.

Howell, E. A., Mora, P., & Leventhal, H. (2006). Correlates of early postpartum depressive symptoms. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10(2), 149–157.

Josefsson, A., Angelsioo, L., Berg, G., et al. (2002). Obstetric, somatic, and demographic risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstetrics and gynecology, 99(2), 223–228.

Kurz B. (2005) Depression and Mental-Health Service Utilization Among Women in WIC. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 14(3–4):81–102.

Mark, T. L., Palmer, L. A., Russo, P. A., & Vasey, J. (2003). Examination of treatment pattern differences by race. Mental Health Services Research, 5(4), 241–250.

Melfi, C. A., Croghan, T. W., & Hanna, M. P. (1999). Access to treatment for depression in a Medicaid population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 10(2), 201–215.

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., Sampson, N. A., et al. (2011). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National comorbidity survey replication. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1751–1761.

Nonacs, R., & Cohen, L. S. (1998). Postpartum mood disorders: Diagnosis and treatment guidelines. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 2), 34–40.

O’Hara, M. W., & McCabe, J. E. (2013). Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 379–407.

O’Mahen, H. A., & Flynn, H. A. (2008). Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 17(8), 1301–1309.

Services USDoHaH. Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity - a supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. 2001; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44243/. Accessed October 7, 2015.

Shivakumar, G., Brandon, A. R., Johnson, N. L., & Freeman, M. P. (2014). Screening to treatment: Obstacles and predictors in perinatal depression (STOP-PPD) in the dallas healthy start program. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 17(6), 575–578.

Smith, M. V., Shao, L., Howell, H., Wang, H., Poschman, K., & Yonkers, K. A. (2009). Success of mental health referral among pregnant and postpartum women with psychiatric distress. General Hospital Psychiatry. 31(2), 155–162.

Song, D., Sands, R. G., & Wong, Y. L. (2004). Utilization of mental health services by low-income pregnant and postpartum women on medical assistance. Women and Health, 39(1), 1–24.

Zlotnick, C., Johnson, S. L., Miller, I. W., Pearlstein, T., & Howard, M. (2001). Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. The American journal of psychiatry, 158(4), 638–640.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (5R01MH77683-2) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (5P60MD000270-10) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01312883 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00951717.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no financial relationships with the sponsoring organization or any conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bodnar-Deren, S., Benn, E.K.T., Balbierz, A. et al. Stigma and Postpartum Depression Treatment Acceptability Among Black and White Women in the First Six-Months Postpartum. Matern Child Health J 21, 1457–1468 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2263-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2263-6