Abstract

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common adult-onset neurological disorders which produce motor and non-motor symptoms. To date, there are no gold standard pathological hallmarks of ET, and despite a strong genetic contribution toward ET development, only a few pathogenic mutations have been identified. Recently, a pathogenic FUS-Q290X mutation has been reported in a large ET-affected family; however, the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying FUS-linked ET is unknown. Here, we generated transgenic Drosophila expressing hFUS-WT and hFUS-Q290X and targeted their expression in different tissues. We found that the targeted expression of hFUS-Q290X in the dopaminergic and the serotonergic neurons did not cause obvious neuronal degeneration, but it resulted in motor dysfunction which was accompanied by impairment in the GABAergic pathway. The involvement of the GABAergic pathway was supported by rescue of motor symptoms with gabapentin. Interestingly, we observed gender specific downregulation of GABA-R and NMDA-R expression and reduction in serotonin level. Overexpression of hFUS-Q290X also caused an increase in longevity and this was accompanied by downregulation of the IIS/TOR signalling pathway. Our in vivo studies of the hFUS-Q290X mutation in Drosophila link motor dysfunction to impairment in the GABAergic pathway. Our findings would facilitate further efforts in unravelling the pathophysiology of ET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common adult-onset, age-progressive neurological disorders, affecting about 0.9 % of world population (Louis and Ferreira 2010). Despite its high prevalence, the exact pathophysiology of ET remains to be elucidated. ET is a heterogeneous disorder involving both motor (such as tremor) and non-motor (such as cognitive, psychiatric, dementia and sensory) symptoms (Chandran and Pal 2012). Unlike in neurodegenerative condition such as PD where there is a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons (Benazzouz et al. 2014), no obvious neuronal loss has been reproducibly observed for ET. Neuropathological evidence suggests abnormalities in the GABAergic Purkinje cells of the cerebellum and their surrounding neuronal populations which likely lead to defects in the cerebellar cortical circuits and output (Louis 2016). Higher mortality rates have been reported in the cases of late-onset ET (Louis et al. 2007), but increased longevity has also been associated with early onset ET and observed in ET patients and their relatives (Jankovic et al. 1995).

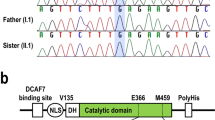

Gene seems to play a major role on the development of ET (Jimenez-Jimenez et al. 2013), although the exact cause and effect relationship is unclear. This is due to limited discoveries of pathogenic ET gene mutations and lack of in vivo ET models. Pathogenic risk variants have been reported for TENM4 (teneurin transmembrane protein 4), and studies of this gene in zebra fish suggested its role on oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination of CNS axons (Hor et al. 2015). A pathogenic mutation (Q290X) has also been recently identified for the FUS/TLS (fused in sarcoma/translated in liposarcoma) gene through exome sequencing in a large ET family from Quebec (Merner et al. 2012). FUS is an RNA/DNA binding protein, and it is involved in the regulation of transcription, RNA splicing, and translational control (Prasad et al. 1994; Belly et al. 2005). Q290X is a nonsense mutation caused by a single-base-pair substitution which results in the truncation of the FUS protein at amino acid 290 in its nuclear export signal motif (Merner et al. 2012). Mutations in other domains of the FUS protein are known to cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (Vance et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2011).

Here, we performed targeted expression analysis (Brand and Perrimon 1993) of hFUS-Q290X in Drosophila and characterised its phenotype. In addition, we examined the involvement of the GABAergic system, the serotonergic system, and the IIS/TOR signalling pathway, and conducted therapeutic challenges.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains and generation of transgenic flies

Flies were raised on standard corn meal containing food and genetic crosses were performed at 25 °C. GAL4 lines (GMR-GAL4, ple-GAL4, Ddc-GAL4 and OK371-GAL4) and RNAi lines to dFUS (stock numbers 32990 and 34839) used were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre (BDSC). For generation of the wild-type transformation construct, wild-type hFUS cDNA was excised from the pCMV-FUS plasmid DNA (from Origene) using restriction enzymes XhoI and XbaI and subcloned into the XhoI and XbaI digested pUAST-attB transformation vector. The Q290X mutation was generated using the Quick-Change II Site-Directed Mutagensis Kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s instructions, with the pUAST-attB-wild-type hFUS as the DNA template. All plasmid constructs which had been subcloned into the transformation vector were verified by sequencing before sent for transgenesis at Best Gene Inc. To avoid possible contribution of second site mutation which might have arisen during transgenesis, the transgenic lines were backcrossed into yw (from Bloomington) for six generations.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from head homogenates of approximately 30–50 flies of the respective genotypes. Adult flies were exposed to liquid nitrogen followed by shaking to separate the heads from the bodies. Heads were collected and homogenised in M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific) in the presence of protease inhibitor (Roche). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific). 50–150 µg of total proteins of each samples were denatured by heating to 95 °C and loaded on SDS–PAGE gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose paper, blocked with 1 × PBST + 5 % non-fat milk and incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. This was followed by incubation in secondary antibody. Protein expression was detected by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-FUS (from Bethyl Labs, cat. #A300-302A, 1:1000 dilution), rabbit anti-N-terminal hFUS (LSC, unpublished result, 1:1000), mouse anti-serotonin (Thermo Scientific, 1:40 dilution), and mouse anti-tubulin (Sigma, 1:10,000 dilution). Secondary antibodies used were HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse/rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., 1:4000 dilution).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain fixation and antibody staining were carried out according to the standard protocol. Briefly, adult brains were dissected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) then fixed with 4 % formaldehyde followed by a few washes in PBT (PBS + 0.1 % Triton X-100). After blocking with 3 % BSA (in PBT), brain samples were incubated in primary antibody (rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase, Sigma, 1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C with rotation. After removal of primary antibodies, samples were washed with PBT followed by incubation in secondary antibody (Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:500). After washes, samples were incubated with Vectashield and analysed by Carl Zeiss Upright Confocal Microscope.

Light microscopy of adult eyes and wings

For adult eye microscopy, heads were removed and glued to masking tapes, and then, photos were captured by a digital camera through eye piece of a scanning microscope (Olympus). Photography of wing phenotypes was carried out similarly by placing flies on CO2 gas pad on their backs.

Longevity and climbing assays

Flies were crossed at 25 °C on standard corn meal containing food, and at day 1 post-eclosion, males and females were separated. Adult flies were aged at 25 °C. Life span was scored at a density of 20 flies per vials. Flies were transferred to fresh vials thrice a week, followed by scoring of dead flies at every transfer. Dead flies were confirmed under microscope to assure that they had stopped moving completely. Locomotion was analysed using negative geotaxis assay where approximately 20 flies were left to acclimatise to 20-cm height in 1 min. The percentage of flies that climbed passed the 20-cm height was recorded. For drug treatment, female flies were aged to 10 days, then exposed to drug and subjected to negative geotaxis assay. Gabapentin (Sigma–Aldrich) was mixed in the food at the concentration of 0.1 mg/ml according to the published literature (Reynolds et al. 2004).

RT-qPCR

For qPCR, approximately 150–200 fly heads were homogenised on ice. Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Conversion to cDNA was done using High-Capacity Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems), with 1 µg each of RNA template. qPCR was carried out using GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) with the 7500 Fast Real Time System (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences used to detect Drosophila melanogaster mRNA expressions were as follows: GABA A -R (Fwd: 5′-GCGAAATTCAGTTCGTGCGT-3′, Rev: 5′-ACAACGATCAGTCCAGAGGG-3′), GABA B -R (Fwd: 5′-CAACGACAGCGAGTGTGAG-3′, Rev: 5′-GATGGGTGCGGAATAGAGTG-3′), NMDA-R1 (Fwd: 5′-GTGGAGCTCTCCAACATGTATC-3′, Rev: 5′-AATCCCAGATGAAGGCCATAAG-3′), NMDA-R2 (Fwd: 5′-TCCTACAGCGAGTACGTCTAA-3′, Rev: 5′-CTTTCGCTATCTCGTCCCTAAC-3′), 4E-BP (Fwd: 5′-TCAGCTAAGATGTCCGCTTC-3′, Rev: 5′-AGATAAGTTTGGTGCCTCCA-3′ and atub84b (Fwd: 5′-GATCGTGTCCTCGATTACCGC-3′, Rev: 5′-GGGAAGTGAATACGTGGGTAGG-3′). Primer sequences used to detect expression of hFUS from transgenes were Fwd: 5′-ACGGACACTTCAGGCTATGG-3′ and Rev: 5′-TACCGTAACTTCCCGAGGTG-3′. Calculation of relative gene expression from RT-qPCR experiments was performed using the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Statistical analysis

For all experiments, data from at least two to three biological replicates were obtained. For each biological replicate, three rounds of technical replicates were conducted. In this case, biological replicates involved samples obtained from separate batches of genetic crosses which were conducted repeatedly. Technical replicates involved samples from same batches of genetic crosses. Negative geotaxis assay was analysed by Pearson Chi-square (df = 1) on data obtained from three biological replicates. RT-qPCR analysis of FUS mRNA levels was tested using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons on data obtained from two biological replicates. RT-qPCR analysis of GABA-R, NMDA-R, and 4E-BP expression levels was tested using one sample Student’s t test (95 % confidence interval) on data obtained from three biological replicates. Protein band quantification on Western Blot (quantified using Image J program) was tested using one sample Student’s t test (95 % confidence interval) on data obtained from three and five biological replicates (for Western Blot results of FUS protein and for Serotonin levels, respectively). Longevity assay was analysed using Kaplan–Meier analysis with Cox regression (95 % confidence interval) on data obtained from five biological replicates. Software used to perform statistical analysis was IBM-SPSS Statistical 21. Significant differences were defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Phenotypic characterization of hFUS-Q290X in Drosophila

To characterise the phenotypes associated with hFUS-Q290X mutation, we generated transgenic Drosophila carrying hFUS and targeted their expression in different tissues with the versatile binary GAL4/UAS system (Brand and Perrimon 1993). The effects of overexpression of hFUS-WT and hFUS-Q290X were analysed. As the hFUS-Q290X mutation has been previously shown to be degraded by the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway, we checked mRNA expression of hFUS-WT and hFUS-Q290X transgenes using RT-qPCR and found high levels of expression after 15 days of ageing (Fig. 1a). This was further confirmed by intact and similar expression levels of both the full length hFUS-WT and the truncated hFUS-Q290X proteins (shown on Western Blots, Fig. 1b). Overexpression of hFUS-WT in the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems resulted in the wing-folded phenotype which could be partially rescued by reducing the endogenous dFUS expression (Fig. 1c), suggesting conservation of genes and pathways between Drosophila and human.

Expression from the hFUS transgenes and the ability of knock down of endogenous dFUS to rescue wing defect caused by ectopic expression of hFUS-WT. a RT-qPCR showing mRNA expression from transgenic lines carrying UAS-hFUS-WT and UAS-hFUS-Q290X (after 15 days of aging), driven by Ddc-GAL4. The relative expression levels of the two transgenes are shown. Note that both transgenic lines have similar expression levels. Statistics used is one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons. b Western Blot analysis showing protein expression of full-length hFUS-WT (around 75 kDa) and truncated hFUS-Q290X (around 45 kDa) (left and right columns, respectively) under the control of GMR-GAL4. Note that although both protein extracts were run on the same gel, the blot were divided into two halves to be incubated with two different sources of the anti-FUS antibodies. This is due to the inability of both antibodies to cross react with the full length and the truncated hFUS. Note that the commercial antibody used to detect the full length protein does not detect the endogeneous dFUS in the control lane (left panel) as it recognises an epitope which maps to a region between residues 1 and 50 of hFUS, which is absent in dFUS (Stolow and Haynes 1995). The antibody used to detect the truncated hFUS protein was generated using a peptide at residues 130–140 of hFUS. Note that there is one strong band detected at the position expected for the truncated FUS protein. Currently, the presence of the lighter bands in the control lane (right panel) is still unclear, but those are likely to be unspecific signals. c Rescue of wing folded phenotype by knock down of endogenous dFUS. Ectopic expression of hFUS-WT with Ddc-GAL4 results in wing folded phenotype (middle panel). This phenotype can be partially rescued by knocking down of endogenous dFUS expression (right panel), with either RNAi lines 32990 or 34839. Note that as compared with the control wings (left panel), rescued wings lack shiny appearance of the wild-type wing

Next, we wanted to analyze motor function in flies expressing these transgenes. Although, currently, we do not have an assay to measure tremor, we analysed locomotion using negative geotaxis (climbing) assay. As targeting expression of other neurodegenerative mutants in the dopaminergic and the serotonergic neurons using Ddc-GAL4 has previously implicated those genes in motility (Angeles et al. 2014), we drove our transgenes with this driver. Overexpression of hFUS-Q290X resulted in progressive locomotor impairment (Fig. 2a, shown separately for females and males), suggesting a dominant-negative mode of action of the Q290X mutation. The observed locomotor impairment was not accompanied by obvious neuronal degeneration as shown by intact DA neurons when hFUS-Q290X was expressed with Ddc-GAL4 (Fig. 2b, c). Since the presence of degeneration in the visual system can be reflected by external rough eye morphology, we expressed hFUS-Q290X in the visual system with GMR-GAL4 and found wild-type eye morphology (Fig. 2d), suggesting absence of obvious degeneration. Impairments in climbing ability and degeneration were observed in flies overexpressing hFUS-WT (Fig. 2a–d), consistent with the previous reports (Chen et al. 2011; Mitchell et al. 2013).

Targeted-expression of hFUS-Q290X results in movement impairment in the absence of neuronal degeneration. a Negative geotaxis assays (of females and males) reflecting locomotor ability of flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X and hFUS-WT under the control of Ddc-GAL4. Control flies are Ddc-GAL4/+. Note that flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X begins to show climbing impairment after 10 days of aging and this deteriorates rapidly after 30 and 40 days of aging. Overexpression of hFUS-WT starts to cause strong climbing impairment after 10 days of aging. Data shown are from three separate rounds of experiments (n = 3). Statistics used is Pearson Chi-square (p value ≤ 0.001 to indicate highly significance as denoted by **). b Quantification of DA neuronal clusters in the adult brain samples aged to 60 days (for hFUS-Q290X and Control) and to 40 days (for hFUS-WT). The quantification of DA neuron numbers in flies overexpressing hFUS-WT could only be carried out for samples aged till 40 days, because these flies did not survive to 60 days. Note that while reduction in neuronal numbers is significantly present in certain DA clusters of flies overexpressing hFUS-WT, there is no significant difference in the number of neurons between the control flies and the flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X. Statistics used is one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons (p value ≤0.001 to indicate highly significance as denoted by **; p value ≤0.05 to indicate significance as denoted by *). c Representative pictures showing DA neurons in the adult brain. The genotypes are: Ddc-GAL4/+ (control, left column); Ddc-GAL4/UAS-hFUS-WT (middle column); and Ddc-GAL4/UAS -hFUS-Q290X (right column). With the exception of the Ddc-GAL4/UAS-hFUS-WT samples which have been aged to 40 days, both the Ddc-GAL4/+ and the Ddc-GAL4/UAS-hFUS-Q290X samples have been aged to 60 days. Overexpression of hFUS-WT results in reduction of DA neurons; however, the number of DA neurons remains normal in flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X. The main clusters of DA neurons examined are PAL (paired anterior lateral), PPM1, 2, 3 (paired posterior medial clusters 1, 2, and 3), PPL1, 2 (paired posterior lateral clusters 1 and 2). d Comparison of external structures of the adult ommatidia. Note that while overexpression of UAS-hFUS-WT (middle panel) results in mild rough eye, overexpression of hFUS-Q290X (right panel) causes no sign of degeneration as reflected by wild-type ommatidia similar to that seen in the control (GMR-GAL4/+, left panel)

To demonstrate that the observed phenotypes in flies overexpressing hFUS- Q290X were not due to toxicity as reported when hFUS-WT was overexpressed (Machamer et al. 2014), we drove expression of both transgenes with OK371-GAL4. We found that while overexpression of hFUS-WT resulted in pupal lethality, flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X were viable to the adult stage without obvious abnormalities (data not shown).

Expression of hFUS-Q290X results in impairement of the GABAergic system

To determine the involvement of the GABAergic system in our overexpression study, we performed RT-qPCR analysis to check mRNA expression levels of the two major types of GABA-R in Drosophila, the ligand-gated ion channel-type GABA A -R and the metabotropic GABA B -R (Lei et al. 2013). As the GABAergic transmission has been shown to be regulated by N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation (Xue et al. 2011), we also analysed mRNA expression level of the two major NMDA-R subunits (NMDA-R1 and NMDA-R2). Interestingly, not only that overexpression of hFUS-Q290X caused a decrease in the mRNA expression levels of these receptors (after aging to 15 days), but there also seemed to be gender specific differential downregulation of these receptor subunits (Fig. 3a, b). While GABA A -R was significantly downregulated in males, GABA B -R was significantly downregulated in females (Fig. 3a). Similarly, while NMDA-R1 was preferentially downregulated in females, NMDA-R2 was preferentially downregulated in males (Fig. 3b). It is interesting to note that although overexpression of hFUS-WT caused a strong locomotion phenotype, it did not significantly affect the expression levels of these receptors (Fig. 3a, b). This suggests that the observed locomotion phenotypes in flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X and hFUS-WT were differentially regulated at the molecular level.

Expression of hFUS-Q290X causes impairment in the GABAergic system. a, b The mRNA expression levels of GABA-R and NMDA-R in flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X and hFUS-WT under the control of Ddc-GAL4. Control flies are carrying one copy of Ddc-GAL4 alone. All flies have been aged for 15 days before mRNA extraction. Results are normalised against the controls. Note that while GABA A -R is downregulated in the males, GABA B -R is downregulated in the females. Similarly, while NMDA-R1 is preferentially downregulated in the females, NMDA-R2 is preferentially downregulated in the males. The levels of GABA-Rs and NMDA-Rs are not significantly affected in flies overexpressing hFUS-WT. Statistical significance of RT-qPCR results is calculated using Student’s t test (p < 0.01, as denoted by **). c Rescue of climbing defect of female flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X under the control of Ddc-GAL4. The ability of gabapentin to rescue the climbing defect is monitored for flies which have undergone 20 and 30 days of aging. Note that treatment with gabapentin is able to rescue the climbing ability of flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X to very similar degree as those observed in the control flies. Statistical analysis was performed using Pearson Chi-square (with p values of 0.008 and 0.009 as denoted by ** for 20 days and 30 days of aging, respectively)

To further demonstrate that the impaired GABAergic system contributed to the decline in locomotion, we performed rescue experiment with gabapentin. Gabapentin was initially synthesised to mimic GABA and able to increase GABA biosynthesis and non-synaptic GABA neurotransmission (Kwan et al. 2001), and it is currently used in the clinic as one of the treatment options for ET (Deuschl et al. 2011). We found that gabapentin was able to rescue the locomotion phenotype caused by overexpression of hFUS-Q290X (Fig. 3c).

Expression of hFUS-Q290X results in life span extension, downregulation of the insulin/insulin-like growth factor signalling (IIS) pathway and increase in serotonin expression

Next, we monitored longevity in our transgenic flies and found that while flies overexpressing hFUS-WT had short life span (yellow in Fig. 4a–d), flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X lived significantly longer. The increase in life span was observed when hFUS-Q290X was overexpressed in the dopaminergic neurons (green in Fig. 4a, b) and in both the dopaminergic and the serotonergic neurons (green in Fig. 4c, d). As the insulin/insulin-like growth factor-like signalling (IIS) pathway has been implicated in the regulation of life span (Jia et al. 2004), we analysed the expression of one of the members (4E-BP) in this pathway. Our results showed that while 4E-BP mRNA levels were not significantly different in young (5 days old) control flies and flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X, its mRNA level was significantly increased in aged flies (40 days) (Fig. 4e), indicating downregulation of the IIS signalling pathway.

Expression of hFUS-Q290X causes increased longevity and downregulation of the IIS signalling pathway. a–d Survival curves (females and males shown separately) comparing longevity of control flies (blue in a and b, ple-GAL4/+ or c and d, Ddc-GAL4/+) vs. flies overexpressing one copy of UAS-hFUS-Q290X (green) or UAS-hFUS–WT (yellow). Note that while overexpression of hFUS–WT by either driver results in drastic mortality rate (p value ≤0.001), expression of hFUS-Q290X (a p value = 0.004; b, p value ≤0.001; c p value = 0.015; d p value ≤0.001) causes a significant increase in life span as compared with those of controls. The effect on life span becomes clearer when flies reached 50–70 days of age. Statistics are performed using Kaplan–Meier analysis with Cox regression. e RT-qPCR results comparing mRNA levels of 4E-BP in control flies vs. flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X under the control of Ddc-GAL4 before aging (5 days post eclosion) and after aging (40 days post eclosion). Results are normalised against the controls. Note the increase in 4E-BP mRNA expression level after 40 days of aging. Statistical significance of RT-qPCR results is calculated using Student’s t test (p = 0.008). f Western Blotting comparing serotonin level in control flies vs. flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X under the control of Ddc-GAL4, which has been aged to 15 days. Note the increase in serotonin level in flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X as compared with the control. Band quantification is carried out using Image J program, and statistical significance is performed using Student’s t test (p ≤ 0.001). In all panels, controls are flies carrying one copy of Ddc-GAL4 alone

Serotonin has been known for its roles in controlling the GABAergic (Saitow et al. 2009) and the insulin (Luo et al. 2012) pathways. Using Western Blot analysis, we determined the level of serotonin and found that overexpression of hFUS-Q290X with Ddc-GAL4 resulted in significant increase in the serotonin level in female flies (aged 15 days, Fig. 4f). Interestingly, the antibody that we used did not detect the presence of serotonin in male flies of same age. A likely explanation for this is that the antibody we used only recognised gender specific form of serotonin. Further experiments with different antibodies to test for gender specificity of serotonin changes would be helpful.

Discussions

In this study, we found that despite previous report showing that the hFUS-Q290X truncation mutation was degraded by the NMD pathway, we could get stable expression of this transcript when expressed in Drosophila. It is likely that in ET patients the NMD pathway does not fully suppress the residual and possibly deleterious dominant-negative effect of molecules harbouring premature termination codons (PTCs) such as hFUS-Q290X and, hence, resulting in disease characteristics. The ability to express the truncated FUS protein enabled us to study its dominant-negative effect in Drosophila and revealed some insights on ET disease pathogenesis.

Our results show that flies overexpressing hFUS-Q290X had locomotion impairment in the absence of obvious degeneration. The locomotion impairment was accompanied by downregulation of neurotransmitter expression and the ability of rescue by gabapentin. These suggest that the hFUS gene may not be required for the specification or the maintenance of neurons but may be important at the level of neurotransmission. It is important to note that decreased levels of GABA-R had been observed in postmortem samples from ET individuals (Paris-Robidas et al. 2012). The observed gender specific effects on downregulation of the GABA-R and NMDA-R subunits expression also suggest the possible presence of sexual dimorphism in ET disease mechanisms. Sexual dimorphism occurs in both human (Morrow 2015) and Drosophila. In Drosophila, the sex difference in ethanol sedation has been linked to the expression of a gene that regulates splicing of fruitless (fru) (Devineni and Heberlein 2012). Male specific FruM isoforms exist which regulate sex-specific neural circuits responsible for regulating courtship behaviour (Von Philipsborn et al. 2014). Due to the high conservation of genes and genetic pathways in both human and flies, it is possible that levels of serotonin, GABA-R and NMDA-R showed gender specific differences in our experimental paradigm. It will be interesting to evaluate gender specific differences in clinical drug studies as this can provide an explanation for inefficient drug therapy or adverse effects which may be caused by overactivation of certain pathways in some individuals.

Increased longevity has been associated with cases of early onset ET. However, the opposite was noted in patients having late onset ET, possibly complicated by other comorbidities. It is to be noted that the hFUS-Q290X mutation was identified in patients having early onset ET, and our data show that overexpression of hFUS-Q290X resulted in prolonged life span which was accompanied by downregulation of the IIS/TOR signalling pathway. One of the downstream molecules in the IIS/TOR pathway is Forkhead bOX-containing protein, subfamily O (FOXO) (Kahn 2015), and a direct target of FOXO is 4E-BP. Interestingly, FOXO3A genotype has also been strongly associated with longevity in human (Willcox et al. 2008).

Since serotonin is known for its role in controlling the GABAergic and the insulin pathways, it is likely that upstream of all the observed phenotypes in our overexpression analysis is caused by impairment in the serotonergic pathways. Our observation of a possible role of serotonin on the control of locomotion is corroborated by studies linking increased extracellular serotonin level to impaired larval locomotion through application of drugs that block serotonin transporter (Dasari et al. 2007). Further studies will be required to decipher how the GABA receptors, and the different serotonin receptors or combinations of receptors interact and regulate the resultant receptor signalling in FUS-linked ET.

In summary, we demonstrated that Drosophila expressing hFUS-Q290X could recapitulate certain characteristics found in ET patients such as increased motor dysfunction with age, absence of obvious neuronal loss and possibly longer life span. These phenotypes were accompanied by gender specific reduction in the expression of GABA-R and NMDA-R subunits, rescue of the motor dysfunction with gabapentin, downregulation of the IIS/TOR signalling pathway and increase in serotonin level. Hence, our studies of hFUS-Q290X in in vivo Drosophila model have shed some mechanistic insights on ET pathogenesis. Further phenotypic characterization and evaluation of the involved molecular mechanisms may lead to improvement of clinical diagnosis and therapy for ET.

References

Angeles DC, Ho P, Chua LL, Wang C, Yap YW, Ng C, Zhou ZD, Lim KL, Wszolek ZK, Wang HY, Tan EK (2014) Thiol peroxidases ameliorate LRRK2 mutant-induced mitochondrial and dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet 23:3157–3165

Belly A, Moreau-Gachelin F, Sadoul R, Goldberg Y (2005) Delocalization of the multifunctional RNA splicing factor TLS/FUS in hippocampal neurones: exclusion from the nucleus and accumulation in dendritic granules and spine heads. Neurosci Lett 379:152–157

Benazzouz A, Mamad O, Abedi P, Bouali-Benazzouz R, Chetrit J (2014) Involvement of dopamine loss in extrastriatal basal ganglia nuclei in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 6:87

Brand AH, Perrimon N (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118:401–415

Chandran V, Pal PK (2012) Essential tremor: beyond the motor features. Park Rel Disord 18:407–413

Chen Y, Yang M, Deng J, Chen X, Ye Y, Zhu L, Liu J, Ye H, Shen Y, Li Y, Rao EJ, Fushimi K et al (2011) Expression of human FUS protein in Drosophila leads to progressive neurodegeneration. Protein Cell 2:477–486

Dasari S, Viele K, Turner AC, Cooper RL (2007) Influence of PCPA and MDMA (ecstasy) on physiology, development and behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Eur J Neurosci 26:424–438

Deuschl G, Raethjen J, Hellriegel H, Elble R (2011) Treatment of patients with essential tremor. Lancet Neurol 10:148–161

Devineni AV, Heberlein U (2012) Acute ethanol responses in Drosophila are sexually dimorphic. PNAS 109:21087–21092

Hor H, Francescatto L, Bartesaghi L, Ortega-Cubero S, Kousi M, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Gironell A, Clarimon J, Drechsel O, Agundez JA, Kenzelmann Broz D et al (2015) Missense mutations in TENM4, a regulator of axon guidance and central myelination, cause essential tremor. Hum Mol Genet 24:5677–5686

Jankovic J, Beach J, Schwartz K, Contant C (1995) Tremor and longevity in relatives of patients with Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor and control subjects. Neurology 45:645–648

Jia K, Chen D, Riddle DL (2004) The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C elegans larval development, metabolism and life span. Development 131:3897–3906

Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, Garcia-Martin E, Lorenzo- Betancor O, Pastor P, Agundez JA (2013) Update on genetics of essential tremor. Acta Neurol Scand 128:359–371

Kahn AJ (2015) FOXO3 and related transcription factors in development, aging and exceptional longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70:421–425

Kwan P, Sills GJ, Brodie MJ (2001) The mechanisms of action of commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Pharmacol Ther 90:21–34

Lei Z, Chen K, Li H, Liu H, Guo A (2013) The GABA system regulates the sparse coding of odors in the mushroom bodies of Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 436:35–40

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408

Louis ED (2016) Linking essential tremor to the cerebellum: neuropathological evidence. Cerebellum 15:235–242

Louis ED, Ferreira JJ (2010) How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov Disord 25:534–541

Louis ED, Benito-Leon J, Ottman R, Bermejo-Pareja F (2007) A population-based study of mortality in essential tremor. Neurology 69:1982–1989

Luo J, Becnel J, Nichols CD, Nassel DR (2012) Insulin-producing cells in the brain of adult Drosophila are regulated by the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci 69:471–484

Machamer JB, Collins SE, Lloyd TE (2014) The ALS gene FUS regulates synaptic transmission at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Hum Mol Genet 23:3810–3822

Merner ND, Girard SL, Catoire H, Bourassa CV, Belzil VV, Riviere JB, Hince P, Levert A, Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Noreau A, Diab S et al (2012) Exome sequencing identifies FUS mutations as a cause of essential tremor. Am J Hum Genet 91:313–319

Mitchell JC, McGoldrick P, Vance C, Hortobagyi T, Sreedharan J, Rogelj B, Tudor EL, Smith BN, Klasen C et al (2013) Overexpression of human wild-type FUS causes progressive motor neuron degeneration in an age- and dose-dependent fashion. Acta Neuropathol 125:273–288

Morrow EH (2015) The evolution of sex differences in disease. Biol Sex Differ 6:5

Paris-Robidas S, Brochu E, Sintes M, Emond V, Bousquet M, Vandal M, Pilote M, Tremblay C, Di Paolo T, Rajput AH, Rajput A, Calon F (2012) Defective dentate nucleus GABA receptors in essential tremor. Brain 135:105–116

Prasad DD, Ouchida M, Lee L, Rao VN, Reddy ES (1994) TLS/FUS fusion domain of TLS/FUS-erg chimeric protein resulting from the t(16;21) chromosomal translocation in human myeloid leukemia functions as a transcriptional activation domain. Oncogene 9:3717–3729

Reynolds ER, Stauffer EA, Feeney L, Rojahn E, Jacobs B, McKeever C (2004) Treatment with the antiepileptic drugs phenytoin and gabapentin ameliorates seizure and paralysis of Drosophila bang-sensitive mutants. J Neurobiol 58:503–513

Saitow F, Murano M, Suzuki H (2009) Modulatory effects of serotonin on GABAergic synaptic transmission and membrane properties in the deep cerebellar nuclei. J Neurophysiol 101:1361–1374

Stolow DT, Haynes SR (1995) Cabeza, a Drosophila gene encoding a novel RNA binding protein, shares homology with EWS and TLS, two genes involved in human sarcoma formation. Nucleic Acids Res 23:835–843

Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesalingam J, William KL et al (2009) Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 323:1208–1211

Von Philipsborn AC, Jorchel S, Tirian L, Demir E, Morita T, Stern DL, Dickson BJ (2014) Cellular and behavioural functions of fruitless isoforms in Drosophila courtship. Curr Biol 24:242–251

Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, Chen R, Grove JS, Yano K, Masaki KH, Willcox DC, Rodriguez B, Curb JD (2008) FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:13987–13992

Xue JG, Masuoka T, Gong XD, Chen KS, Yanagawa Y, Law SK, Konishi S (2011) NMDA receptor activation enhances inhibitory GABAergic transmission onto hippocampal pyramidal neurons via presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms. J Neurophysiol 105:2897–2906

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre for the different GAL4 and RNAi strains and Dr. Li Huihua from Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School for advice on statistical analysis. This work was supported by National Medical Research Council (TCR Programme and STAR Investigator Award).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tio, M., Wen, R., Lim, Y.L. et al. FUS-linked essential tremor associated with motor dysfunction in Drosophila . Hum Genet 135, 1223–1232 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-016-1709-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-016-1709-z