Abstract

Objective

Residents of Puerto Rico are disproportionately exposed to social and environmental stressors (e.g., Hurricane María and the 2020 sequence of tremors) known to be associated with psychological distress. Shift-and-persist (SP), or the ability to adapt the self to stressors while preserving focus on the future, has been linked with lower psychological distress, but no study has evaluated this in Puerto Rico. This study examined the association between SP and psychological distress (including that from natural disasters) in a sample of young adults in Puerto Rico.

Methods

Data from the Puerto Rico-OUTLOOK study (18–29 y) were used. Participants (n = 1497) completed assessments between September 2020 and September 2022. SP was measured with the Chen scale and categorized into quartiles (SPQ1–SPQ4). Psychological distress included symptoms of depression (CESD-10), anxiety (STAI-10), post-traumatic stress disorder (Civilian Abbreviated Scale PTSD checklist), and ataque de nervios (an idiom of distress used by Latinx groups). Outcomes were dichotomized according to clinical cutoffs when available, otherwise used sample-based cutoffs. Two additional items assessed the perceived mental health impact of Hurricane María and the 2020 sequence of tremors (categorized as no/little impact vs. some/a lot). Adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated.

Results

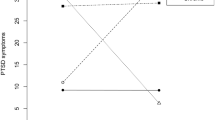

The most commonly reported psychological distress outcome was PTSD (77%). In adjusted models, compared to SP Q1, persons in SP Q2–Q4 were less likely to have elevated symptoms of depression (PR Q2 = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.72–0.85; PR Q3 = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.58–0.73; and PR Q4 = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.35–0.48), PTSD (PR Q2 = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.87–0.98; PR Q3 = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.80–0.93; and PR Q4 = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.70–0.83), anxiety (PR Q2 = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.31–0.48; PR Q3 = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.20–0.37; and PR Q4 = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.07–0.17) and experiences of ataque de nervios (PR Q2 = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.76–0.94; PR Q3 = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.70–0.90; and PR Q4 = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.60–0.78). Compared to persons in SP Q1, persons in SP Q3–Q4 were less likely to report adverse mental health impacts from Hurricane María (PR Q3 = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.55–0.79; and PR Q4 = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.44–0.65) and the 2020 sequence of tremors (PR Q3 = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.61–0.98; and PR Q4 = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.59–0.94).

Conclusion

SP was associated with lower psychological distress. Studies are needed to confirm our findings and evaluate potential mechanisms of action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request to CMP or MCR.

References

MHA. Mental Health in America. Available from: https://mhanational.org/issues/mental-health-america-printed-reports. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Abrams Z (2019) Puerto Rico, two years after María. Monit Psychol 50(8):28

Robles F (2020) Months after Puerto Rico earthquakes, thousands are still living outside. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/us/puerto-rico-earthquakes-fema.html. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Cordero-Guzman H (2016) Poverty in Puerto Rico. Available from: https://centropr.hunter.cuny.edu/events-news/events/seminar-series/poverty-puerto-rico. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Oliveira N (2019) Governor’s refusal to resign drives massive strike, protests in Puerto Rico. Available from: https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ny-governor-refusal-resign-drives-massive-protests-puerto-rico-20190722-eeciqocef5berhzskqrg22kogi-story.html. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Santos-Burgoa C et al (2018) Ascertainment of the estimated excess mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico. Milken Institute School of Public Health. Available from: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_global_facpubs/288/. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Macias RL et al (2021) Después de la tormenta: collective trauma following Hurricane María in a northeastern Puerto Rican community in the United States. J Community Psychol 49(1):118–132

Welton M et al (2020) Impact of hurricanes Irma and María on Puerto Rico maternal and child health research programs. Matern Child Health J 24(1):22–29

Un isla a oscuras, in El Nuevo Dia. Available from: https://huracanmaria.elnuevodia.com/2017/mapas/electricidad/. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Guarnaccia PJ et al (2010) Ataque de nervios as a marker of social and psychiatric vulnerability: results from the NLAAS. Int J Soc Psychiatry 56(3):298–309

ASSMCA. Need assessment study of mental health and substance use disorders and service utilization among the adult population of Puerto Rico. Final Report. Available from: https://assmca.pr.gov/BibliotecaVirtual/Estudios/Need%20Assessment%20Study%20of%20Mental%20Health%20and%20Substance%20of%20Puerto%20Rico%202016.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Guarnaccia PJ (1993) Ataques de nervios in Puerto Rico: culture-bound syndrome or popular illness? Med Anthropol 15(2):157–170

López-Cepero A et al (2022) Association between adverse experiences during Hurricane María and mental and emotional distress among adults in Puerto Rico. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57(12):2423–2432

Liu C et al (2020) Rupture process of the 7 January 2020, M W 6.4 Puerto Rico earthquake. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087718

Acevedo N, Lilley S, Gamboa S (2020) Sad, worried, inconsolable’: earthquakes trigger anxiety in Puerto Rico, post-Hurricane María. Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/sad-worried-inconsolable-earthquake-triggers-anxiety-puerto-rico-post-hurricane-n1112441. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Chokroverty L (2020) 66.4 The early aftermath of earthquakes in puerto rico: enlisting the community in mental health recovery. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 59(10):S101

Leppold C et al (2022) Public health implications of multiple disaster exposures. Lancet Public Health 7(3):e274–e286

Garfin DR et al (2022) Association between repeated exposure to hurricanes and mental health in a representative sample of Florida residents. JAMA Netw Open 5(6):e2217251

Sansom GT et al (2022) Compounding impacts of hazard exposures on mental health in Houston. TX Natural Hazards 111(3):2809–2818

Chen E, Miller GE (2012) “Shift-and-persist” strategies: why low socioeconomic status isn’t always bad for health. Perspect Psychol Sci: J Assoc Psychol Sci 7(2):135–158

Chen L et al (2019) Diurnal cortisol in a sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged chinese children: evidence for the shift-and-persist hypothesis. Psychosom Med 81(2):200–208

Chen E et al (2012) Protective factors for adults from low-childhood socioeconomic circumstances: the benefits of shift-and-persist for allostatic load. Psychosom Med 74(2):178–186

Christophe NK et al (2019) Coping and culture: the protective effects of shift-&-persist and ethnic-racial identity on depressive symptoms in Latinx Youth. J Youth Adolesc 48(8):1592–1604

Chen E, McLean KC, Miller GE (2015) Shift-and-persist strategies: associations with socioeconomic status and the regulation of inflammation among adolescents and their parents. Psychosom Med 77(4):371–382

Kallem S et al (2013) Shift-and-persist: a protective factor for elevated BMI among low-socioeconomic-status children. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md,) 21(9):1759–1763

Stein GL et al (2022) Shift and persist in Mexican American youth: a longitudinal test of depressive symptoms. J Res Adolesc 32(4):1433–1451

Christophe NK, Stein GL (2022) Shift-&-persist and discrimination predicting depression across the life course: an accelerated longitudinal design using MIDUSI-III. Dev Psychopathol 34(4):1544–1559

Christophe NK et al (2021) Culturally informed shift-&-persist: a higher-order factor model and prospective associations with discrimination and depressive symptoms. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 27(4):638–648

Christophe NK, Martin Romero MY, Stein GL (2022) Examining the promotive versus the protective impact of culturally informed shift-&-persist coping in the context of discrimination, anxiety, and health behaviors. J Community Psychol 50(7):2829–2844

Best R, Strough J, de Bruin WB (2023) Age differences in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: March 2020–June 2021. Front Psychol 14:1101353

McIntosh J (2017) Evaluating psychological distress data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1551

Cameron-Maldonado S et al (2023) Age-related differences in anxiety and depression diagnosis among adults in puerto rico during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(11):5922

NIH RePORTER: PR-OUTLOOK: PR Young Adults’ Stress, Contextual, Behavioral & Cardiometabolic Risk. 2021; Available from: https://reporter.nih.gov/search/386ttoh8akWs2RnfA_6SXg/project-details/9824318. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Andresen EM et al (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 10(2):77–84

Spielberger CD (2010) State-trait anxiety inventory. In: Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943

Bromberger JT, Matthews KA (1996) A longitudinal study of the effects of pessimism, trait anxiety, and life stress on depressive symptoms in middle-aged women. Psychol Aging 11(2):207–213

Lang AJ, Stein MB (2005) An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav Res Ther 43(5):585–594

Lang AJ et al (2012) Abbreviated PTSD checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 34(4):332–338

Pearce M et al (2022) Association between physical activity and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat 79(6):550–559

Pavey TG, Burton NW, Brown WJ (2015) Prospective relationships between physical activity and optimism in young and mid-aged women. J Phys Act Health 12(7):915–923

Johnson-Kozlow M et al (2007) Validation of the WHI brief physical activity questionnaire among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Am J Health Behav 31:193–202

Meyer AM et al (2009) Test-retest reliability of the women’s health initiative physical activity questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41(3):530–538

Varma P et al (2021) Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a global cross-sectional survey. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 109:110236

Preocupa deterioro en la salud mental de los jóvenes. Available from: https://www.fundacionintellectus.com/en/preocupa-deterioro-en-la-salud-mental-de-los-jovenes/. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

Orengo-Aguayo R et al (2019) Disaster exposure and mental health among Puerto Rican youths after Hurricane María. JAMA Netw Open 2(4):e192619–e192619

Kessler RC et al (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20(4):359–364

Lee S, Nakashima KI (2019) Do shift-and-persist strategies predict the mental health of low-socioeconomic status individuals? Japan J Exp Soc Psychol 59:107

Lee S, Shimizu H, Nakashima KI (2022) Shift-and-persist strategy: tendencies and effect on japanese parents and children’s mental health. Japan Psychol Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12421. Accessed 10 Dec 2023

United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts: Puerto Rico. [cited 2021; Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR.

Riepenhausen A et al (2022) Positive cognitive reappraisal in stress resilience, mental health, and well-being: a comprehensive systematic review. Emot Rev 14(4):310–331

Griggs S (2017) Hope and mental health in young adult college students: an integrative review. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 55(2):28–35

Acknowledgements

Dr. López-Cepero is funded by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health of the NIH under Award Number 8K12AR084234. Puerto Rico-OUTLOOK is funded by NIH-NHLBI under award number 5R01HL149119-04.

Funding

This article is funded by NIH BIRCWH, 8K12AR084234, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 5R01HL149119-04, 5R01HL149119-04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the scientific aspects of this manuscript. ALC: designed statistical analysis and conceptual model, conducted statistical analyses, data interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. TS, SS, and TL: helped to design the conceptual model, contributed to data interpretation, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. NM: conducted literature review and drafted the introduction of the manuscript. CP and MCR: acquired the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

López-Cepero, A.A., Spruill, T., Suglia, S.F. et al. Shift-and-persist strategies as a potential protective factor against symptoms of psychological distress among young adults in Puerto Rico. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02601-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02601-1