Abstract

Many studies have been conducted to identify potentially useful behavioural markers of harmful behaviour using online gambling data sourced from operators. However, less is known about how such markers could be used to identify higher risk products. The study examined whether certain categories and subcategories of product are more strongly associated with behavioural markers of harm than others. Analyses were based on 6 months of data (N = 100,000 individual gamblers) drawn from the population of UK users of an online gambling website in 2022. Measures included individual-level expenditure data across multiple forms of gambling and a series of literature-informed behavioural markers of harm including declined deposits, easing/removing responsible gambling settings, within-session repeat deposits (or ‘top-ups’), bonus-seeking behaviour and gambling at unusual hours. Negative binomial models examined how well the number of active days playing different products predicted behavioural markers of harm. All markers apart from easing/removing responsible gambling settings appeared to covary with the number of active days engaging in specific product types, most notably slots, in-playing betting and some most forms of combination bets on sports. These findings highlight the potential value of using measurable markers to differentiate the risk and potential harm associated with different online products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As a result of limitations in self-report methodologies (Blaszczynski, et al., 2006), an increasing number of studies are utilizing objective data sourced from gambling operators to gain insights into the characteristics of gambling behaviour and its impacts. Although studies of this nature have been conducted using land-based gambling (e.g. Forrest and McHale, 2022), the majority of these studies have focused on online gambling. The advantages of this approach are that researchers gain access to very large datasets with accurate, often time-stamped participation data that can provide insights into the behavioural profile of online gamblers (e.g. Braverman et al., 2013; Dragicevic et al., 2011; Gainsbury and Russell, 2015; Nelson et al., 2022); evidence of higher risk behaviours or harm (e.g. McAuliffe et al., 2022; Xuan and Shaffer, 2009); and whether safer gambling strategies have a measurable impact upon customer behaviour (e.g. Auer & Griffiths, 2022a, b; Auer et al., 2014). Examples of important behavioural variables which have been captured using online methodologies include the following: how often people play (days or sessions); the nature and breadth of product engagement; expenditure by days or sessions; bet sizes; and how often people deposit or withdraw money from their betting account. Studies have also used longitudinal measures to track changes over time such as whether people appear to engage in forms of chasing behaviour (Auer & Griffiths, 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Xuan and Shaffer, 2009), or if interventions introduced at a point in time have subsequent impacts on behaviour (e.g. Auer et al., 2020).

A number of important insights relating to individual player risk have arisen from this research. Profile and clustering studies show that the vast majority of online gamblers spend relatively low amounts and generally lose, but that it is possible to identify higher risk clusters (often 3–5%) who gamble very frequently (e.g. almost daily), have multiple sessions per day and who bet larger amounts (McAuliffe et al., 2022; Perrot et al., 2018). Many of these people spend well above what are considered safe limits established in land-based gambling studies (Brosowski et al., 2020). Studies relating to player risk show that it may be possible to use operator-sourced data to infer evidence of gambling-related harm using proxy measures. Studies have, for example, investigated the predictors of voluntary self-exclusion (e.g. Catania & Griffiths, 2021; Challet-Bouju et al., 2020; Ukhov et al., 2021), account closure (Braverman & Shaffer, 2012; Xuan and Shaffer, 2009) or responsible gambling interventions (Gray et al., 2012). Important behavioural markers found to predict potential harm or higher risk profiles include measures 0of how often and how much people lose (Dragicevic et al., 2015); the breadth of involvement with different gambling products (LaPlante et al., 2014); and how often people make repeated deposits or top-up their balances during sessions (McAuliffe et al., 2022). Meanwhile, in studies examining the impact of various safer gambling strategies (e.g. messaging, voluntary or mandatory limits), it has been shown that online methodologies can be used to show moderations in behaviour (e.g. gambling expenditure, deposits, session length) (e.g. Auer & Griffiths, 2013, 2015, 2016; Auer et al., 2014). In some of the stronger research designs, objective data has been combined with independent self-report measures of problem or disordered gambling to validate various behavioural markers of harm (e.g. Auer & Griffiths, 2022e; LaPlante et al., 2014; Luquiens et al., 2019; Perrot et al., 2018; Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2017). Broadly, such work has generally confirmed that objective measures capturing the intensity of gambling behaviour, and behavioural markers which could be indicative of risky or harmful patterns of play, tend to be significantly associated with self-reported higher risk gambling.

A question which has, however, received somewhat less attention in this body of research is whether objective behavioural data can be used to identify variations in the risk associated with different gambling products. This is an important question because understanding product risk is a central interest to gambling regulators who have to make decisions about the approval of new products and game features, or what safer gambling standards should be applied to different products. At present, insights generally have to be drawn from theory or by using tools such as Gamgard (Gamguard.com) or ASTERIG (Blanco et al., 2013) that score products on a range of structural dimensions: e.g. event frequency, accessibility, bet types, maximum prizes and continuity. However, as Delfabbro and Parke (2021) have pointed out, these protocols were validated largely on land-based gambling products and often struggle to differentiate product risk within narrow product ranges or contexts. For example, regulators may find that online games may be scored as higher risk because all are available in the home, involve immediate payout of wins and incorporate sounds and graphics. For these reasons, integrating new insights by using behavioural markers of harm using objective behavioural data could further strengthen the empirical risk assessment of gambling products.

Several existing studies using online operator data have presented findings which provide some insights into the issue of online product risk. Auer and Griffiths (2022c), for example, studied the data from 43,721 European online gamblers and presented models that examined how well objective indicators of the structural characteristics of products (e.g. event frequency, return-to-player) predicted outcomes such as theoretical loss and the number of bets per session. Products with shorter event frequencies (which would include slot games) were associated with more bets per session and larger theoretical losses. Another study by Dragicevic et al. (2011) based on 128,788 customers on a European gambling website found that slots and roulette appeared to be most favoured by the highest risk cluster. Other studies suggest that bets placed during sporting events (i.e. ‘in-play betting’) appear to be higher risk than betting prior to events (i.e. pre-event betting) (Gray et al., 2012; LaPlante et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2022). These findings are generally consistent with studies of land-based gambling. Slots are generally considered high-risk products because of their rapid event frequency which is thought to increase the likelihood of chasing losses, impulsive decision-making and increase the cost of play per hour (Delfabbro et al., 2020; Dixon et al., 2017; Dowling et al., 2005; Griffiths, 1993; Parke et al., 2016). In-play betting, also characterised by shorter event frequencies, can involve betting on discrete, often momentary features of a sport or event, and these are referred to as ‘action bets’ or ‘micro-bets’. Betting in-play could also pose greater risk because it offers a greater variety of bet choices and odds, which may be more attractive to higher risk players (Hing et al., 2017; Russell et al., 2019) and provides continuous opportunities to bet while events unfold (e.g. switching to betting on the other team if they score the first goal) which could provide ideal conditions for chasing losses (Parke & Parke, 2019). Russell et al. (2019) found that, in land-based gambling, micro-bets were predominantly chosen by problem gamblers. These findings, taken together, suggest that there may some potential for differentiation of risk between different subcategories of the same product using these dimensions.

The Present Study

In this paper, we examine whether previously identified behavioural markers of harm can be used to gain insights into the relative riskiness of different gambling products. By conducting these analyses, we sought achieve two aims. The first was to examine the potential of behavioural markers of harm to profile concentrations of risky behaviour within product categories. The second was to investigate and validate the small emerging literature relating to variations in online product risk. Based on this foundational work as well as a number of land-based product risk studies, it was possible to propose several hypotheses about which products are likely to have a stronger association with behavioural markers of harm, specifically products which (a) have shorter event frequencies and (b) provide continuous opportunities to bet (and facilitate impulsive decision-making or loss-chasing) and (c) have higher availability (can be played any time). Such characteristics would imply stronger associations between markers of harm and products like online slots, in-play betting, micro-betting and online simulated versions of casino table games with shorter event frequencies and minimal breaks in play. Our results extend previous studies of online product risk (e.g. Brosowski et al., 2020) by including a wider range of products (including slots) and using a single operator. In addition, unlike the study by Auer and Griffiths (2022c) which focused principally on the volume of gambling (e.g. number of bets or theoretical loss), we examined range of behavioural markers such as declined deposits, bonus-seeking behaviour and top-ups which may be more indicative of chasing or financial depletion than how much people are gambling.

Method

Data Sources

The analyses presented in this paper are based on anonymized data provided by the online gambling website Unibet for the first 6 months of 2022 (January to June). Participants were 100,000 people in the UK who had spent money on at least one online gambling product in the specified period. The dataset therefore was in short-form with unique gambling customers in rows and participation variables and other key variables in the columns.

(a) Product Categories

The total number of active days (i.e. number of days on which at least one bet was placed) in 6-month observation period was available for all categories of product. These data made it possible to capture binary participation (i.e. at least one day or participation in a given product in the 6 months) or how often (a frequency or count) of how many days the person was active during the period (min 1 up to maximum of 182).

Wagering categories usually refer to both racing and sports. Given the data available, we were able to subcategorize these based on dimensions relating to the timing of the bet (i.e. ‘pre-event’ or ‘in-play’) and the configuration of different selections and outcomes included in the bet. A bet can be configured to include the outcome of one selection (i.e. ‘single’ bets), or two or more selections (i.e. ‘multiple’ and ‘combination’ bets). A multiple bet involves one stake and requires all selections to be successful for the bet to win. The structural implications of these requirements typically mean larger prizes, lower stakes and a lower win probability. Importantly, the prize-to-stake ratios increase, and the win probabilities decrease, with each additional selection added to a multiple bet. Also, the combination of multiple selections into one bet means that the margins for each selection are also combined, thus providing an overall larger margin for the operator and lower return to the player (Newall & Cortis, 2021; Newall et al., 2021). In contrast, combination bets combine different permutations of bet selections, with each additional variation requiring an additional stake, and are paid in all-in-one transaction. Combination bets tend to offer a much lower prize-to-stake ratio but a higher win probability.

Additionally, to understand how availability and gambling at unusual hours affects sports betting, we were also interested in distinguishing between sports bets based on popularity. For example, anecdotal evidence had suggested that late-night sports betting was possible provided there was a willingness to bet on less established sports (e.g. Russian table tennis) when more established sports (e.g. soccer) were not available. To do this, we devised a new betting product category referred to as ‘less established sports’. This was achieved by grouping all bets on sports and events falling outside of top 10 most popular.Footnote 1 Finally, we were able to subcategorize horse and dog racing products into single bets or multiple bets.

Data were also available on non-wagering products including casino table games, poker, bingo and slots. Six subcategories of table casino games were created: roulette (live or software), blackjack (live or software) and a combined category (live or software) of other table games (e.g. baccarat, stud poker, sic bo). In the ‘software’ versions, the game experience is simulated and there is no dealer, and in the ‘live’ versions, the games are streamed live, face-to-face with a real dealer. Finally, multi-player poker gamesFootnote 2 were subcategorized into cash poker or tournament poker. In tournament poker, players pay an entry fee and money is paid according to where players finish in the tournament (i.e. when they run out of chips). In contrast, in cash poker, there is no fixed point of entry or exit, a player can join or quit the table at any time and can win or lose money on a hand-by-hand basis. The full range of product variations is presented in Table 1. Options for subcategorizing slots and bingo were too numerous and complex to be included for this analysis but should be considered for future research.

(b) Total Net Expenditure

This was the total amount spent by gamblers after considering wins and losses. This information was available for each of the product categories and subcategories outlined above.

(c) Behavioural Markers of Harm

The dataset included (for each individual) how often they had made deposits; had deposits rejected because their account had no funds; had deposits declined by the payment provider or bankFootnote 3; number of visits to bonus page when no bonus was availableFootnote 4; removing or easing responsible gambling (RG) settings (e.g. increasing spend limit, removal of restrictions altogether); number of hours spent online with open gambling sessions at times chosen by under 5% of customers in the same time zone (unusual hours); and how many repeat deposits (i.e. ‘top-ups’) are made during gambling sessions. These were measured as frequencies across the 6 months (a count variable).

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v.28. Spearman correlations were used to examine the ordinal association between the frequency of gambling based on the total active days for each product category and subcategory and the frequency of the markers of harm. The association between product any category/subcategory and the markers of harm was then modelled using a series of negative binomial regressions after confirming that Poisson regression was not appropriate due to over-dispersion in the outcome measures. The dependent measures in these models were the frequencies with which the harm indictors occurred over the 6 months, whereas the independent measures were product participation (number of days active in each product up to a maximum of 182 days). For example, a score of 5 on declined deposits meant that a person had 5 declines in 6 months whereas a 5 for roulette (live) meant that a person had spent money on this game on 5 days. An initial linear regression was run using multi-collinearity diagnostics to identify variables which had high variance inflation factors (4 or higher). Models were built in stages. All variables with Spearman correlations 0.20 or greater were initially considered for the models. Variables with correlations lower than this were then entered sequentially, but it was soon evident that no variables with Spearman correlations below 0.15 would be significant or have any further impact on the models. In essence, the aim was to produce parsimonious models that were stable such that no further changes or additions influenced the set of predictors included and which led to no significant change in model fit (Akaike’s and Bayesian information criteria).

Results

(a) Gambling Participation

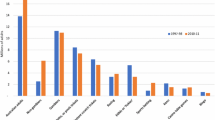

Table 1 summarizes the participation rates and expenditure associated with each of the product categories. The most popular products in terms of overall participation were slots (50%), single bets on racing (42%), single pre-event bets on sports (31%), single in-play bets on sports (19%) and combination pre-event bets on sports (18%). Only a minority of customers placed bets as multiples (2–4%); however, 12% had placed a bet on a less-established sports. Except for roulette (15.7%), participation in table casino games and poker and bingo products was generally much lower. Participation was higher in live versions of roulette and blackjack relative to the software versions. The weekly conversion rate shows the ratio of weekly to overall participation and is an indicator of whether certain products are more likely to be played with greater regularity (i.e. weekly). This appears to most common for poker, slots and some forms of sports betting. The highest conversion rate, by some margin, was for poker, with around 18% of customers playing on at least a weekly basis. Slots, in particular, stand out from other products by having the highest overall and weekly participation rate suggesting slots are the source of the highest absolute number of regular gamblers. Two expenditure estimates are provided: net revenue includes wins, whereas net losses only consider the distribution of values where a loss has occurred. Both show that losses tended to be highest for slots and combination bets on racing, but the figures for other products are more difficult to rank.

(b) Gambling Frequency and Risk Indicators

The prevalence of the six behavioural markers of harm over the 6 months we considered was generally low in the sample, although some individuals had many instances of the behaviour: bonus page visits without a bonus being available (M = 3.19, SD = 11.44, range 0 to 1056); gambling at unusual hours (M = 2.76 h, SD = 11.75, range 0 to 573); removing or easing RG settings (M = 0.13, SD = 1.05, range 0 to 72); top-ups during sessions (M = 2.35, SD = 11.41, range = 0 to 624); declined deposits (no funds) (M = 0.78, SD = 7.75, range 0 to 750); and decline deposits (payment provider) (M = 4.88, SD = 17.64, range 0 to 764). The median value was 0 for all indicators except declined deposit (payment provider) for which it was 1.0.

Table 2 shows the relationship (Spearman correlations) between the frequency of potential markers of harm and the number of active days people played different products. Bonus page visits were most strongly associated with participation in slots, live roulette and other live table games. Gambling at unusual times was also associated with these three products, and with some forms of sports betting (less-established sports, combination bets and single in-play bets). Topping-up during sessions (a potential indictor of chasing) was most strongly associated with slots, combination bets on sports and racing, single bets (in-play only) and live versions of blackjack and roulette. Removing or easing RG settings generally did not prove useful in differentiating the products. Declined deposits (payment provider) also generated similar results as the other markers: slots and live table games (excluding blackjack) emerged as most strongly related. Similarly, when we examined what is one of the most definitive indicators, declined deposits (no available funds), we found that the same activities emerged most strongly: slots, live roulette, other live table games and in-play combination bets on sports.

To further test the validity of these findings, it was important to examine whether these products emerged when controlling for other types of participation. A series of negative binomial regressions were used to ascertain which products were the strongest predictors of the markers of harm while controlling for participation in other products (Table 3). Incidence ratios signify the increase in the incidence of the marker of harm in each subpopulation of players (by product) associated with each additional day of participation. In other words, the dependent measures in each block are the frequency or incidence of the harm indicators whereas the independent measures are the number of days active in each product. The incidence ratios indicate the percentage increase in the frequency of the harm indictors occurring within 6 months based on a one day increase in days active on each product. For example, 1.04 means that for each one additional day active, the frequency of the respective harm indicator increases by 4%. As can be seen, the incidence ratios values are generally small and only slightly above 1, but would indicate how 20 or 30 day increments in these variables over a 6 month period could have a meaningful effect on the incidence of markers of harm. Table 3 shows that slots emerged as a significant predictor for all 5 of the markers, live roulette and combination bets on sports for 4 of them and other live table games for 3 of them. All other activities appeared only once and principally for the topping-up marker. These results suggest that increasing engagement in most products is associated with an increased incidence of topping up, whereas only very specific products appear to be associated with the emergence of other behavioural markers of harm.

(c) Do Behavioural Markers of Harm Indicate Greater Risk for Certain Product Types?

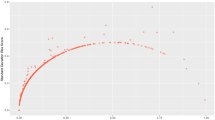

A simple empirically based way to examine this question is to examine the average magnitude of the correlations presented in Table 2 for each of the gambling products (averaging across the columns). Figure 1 shows that the mean correlation (excluding the ‘removal or easing of RG settings’ marker which yielded no significantly meaningful correlations) was noticeably higher for slots (a medium effect size, 0.34). The next small cluster of products were the live table games (except blackjack) and combination bets on sports (whether pre-event or in-play). All other activities had generally weak associations with the markers of harm, with most of the correlations being under 0.1 and therefore explaining less than 1% of the variance in the incidence of markers of harm. By comparison, the amount of variance explained by the number of days active on slots was over 11 times higher and 4 times higher for the next 3 ranked products.

Products listed in order by mean Spearman correlation with various markers of harm in Table 2

Discussion

Overview

In this paper, we examined whether behavioural markers of harm varied depending on the numbers of days players were actively engaging in different gambling products. The analysis was intended to confirm the utility of the behavioural markers of harm as ways to identify products with a potentially higher risk profile, but also strengthen the relatively small evidence base relating to variations in the riskiness of different online products. The results showed that there were consistently larger associations between various behavioural markers of harm and the number of active days on specific gambling activities. Specifically, short event frequencies (e.g. slots and in-play betting), betting on different permutations of more than one bet selection in a single transaction (i.e. combination bets) and, contrary to our expectations, engaging in live rather than simulated table games play were the three structural configurations of products which appeared more strongly associated with patterns of riskier play. This risk was inferred through evidence of behavioural markers of harm identified in previous research. These included a higher frequency of bonus seeking, topping-up balances with repeat deposits, gambling at statistically unusual hours and declined deposits because of a lack of funds or because of suspicious depositing behaviour. These findings suggest that behavioural markers empirically supported in other studies (e.g. Auer & Griffiths, 2022c; Brosowski et al., 2020; McAuliffe et al., 2022) as indications of potential individual risk may also have value in the assessment of product risk profiles. In effect, it may be possible to use behavioural markers as a method to profile which product types (either existing or proposed for the market) have the potential to encourage riskier behaviours as the level of engagement increases.

Insights into Product Risk

The results confirm and build upon a small emerging literature relating to the appraisal of the relative riskiness associated with different gambling products. For example, Auer and Griffiths (2022c) found that products with a shorter event frequency (most notably online slots) tended to be associated with a higher frequency of bets per session and a higher theoretical loss. Slots also emerged as a more popular activity in higher risk gambling clusters identified by Dragicevic et al. (2011) and in a major multi-operator study in the UK by Forrest and McHale (2022) who observed that around 60% of total revenue appeared to be derived from slot games. The high risks associated with slot games in online environments is borne out by a broader literature derived from land-based studies (e.g. Brosowski et al., 2020; Delfabbro & Parke, 2021; Delfabbro et al., 2020; Dowling et al., 2005). Slot games have a very short event frequency (the interval between wager and outcome) which is often less than three seconds. The capacity to play quickly and continuously is thought to facilitate higher rates of expenditure per unit time (Auer & Griffiths, 2022c), encourage chasing (Parke et al., 2016) and contribute to a greater likelihood of impaired control and cognitive immersion into the activity (Dixon et al., 2017). In effect, people are more likely to lose track of time and expenditure when they play this type of game. In this study, it is important to note that the potential risks of slots may not necessarily be borne out just by inspecting average expenditure. Online slot games appear to be the most popular online activity in the UK by participation rates. The entry price of these activities is generally low and, as Forrest and McHale (2022) and this study also observed, the majority of people spent relatively low amounts and session length can often be short. In fact, as we show here, people may often spend more money on sports and other casino activities in single sessions. The issue with slots, however, is that slot play is more likely to transition from overall participation to regular participation than some other activities (a higher conversion rate). Slots also appear to emerge more commonly in higher risk clusters of players because this product appears more likely to encourage higher levels of engagement amongst a percentage of higher risk individuals.

The observation that greater engagement in in-play sports betting emerged as being more strongly associated with risk indicators bears out the findings of several online tracking studies (e.g. Gainsbury et al., 2020; Gray et al., 2012; Hing et al., 2017; LaPlante et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2022). Betting in-play may facilitate more impulsive or reactive gambling behaviour in comparison to betting prior to events. In-play betting is more dynamic, could involve spur-of-the-moment decisions about the progress of the betting event (e.g. who will score the next goal) and introduces micro-betting opportunities with very short event frequencies. Previous research by Hing et al. (2019) and Russell et al. (2019) found that impulsive betting on micro-events, often driven by promotions, was the primary concern arising from their research, with most micro-betting being undertaken by people classified as problem gamblers by the PGSI. These findings are also consistent with research proposing that micro-betting can facilitate loss chasing, a key feature of disordered gambling, by permitting immediate re-staking following rapid feedback on gambling outcomes (Parke & Parke, 2019).

We were also interested in how the configuration of sports bets (e.g. single, multiple, or combined) might be associated with riskier play. We generally found that combined bets were most related to markers of harm, multiple bets least related and single bets somewhere in-between. The finding that multiple bets posed fewer risks than other bet configurations is somewhat surprising when considered in the context of some of the previous literature. Their higher multiplier potential, larger prizes and overall higher margins (i.e. lower returns to player) might suggest a riskier product profile (Cornish, 1978; Newall et al., 2021). However, having other structural features such as a lower cost of play (single stake, lower bet size) and longer payout intervals (several months in some cases) (Newall et al., 2021), a multiple bet shares some structural similarities with some of the lowest risk products currently available, such as lottery tickets (see Delfabbro & Parke, 2021). It could also be speculated that this may be because more informed bettors think multiples offer poor value, or because at-risk and disordered gamblers regard these as too speculative (difficult to win, ineffective for chasing losses) and that combination bets provide a more realistic chance of winning. Accordingly, the higher relative risk of combination bets would make intuitive sense because they have a relatively higher cost of play (multiple staking in a single bet; larger bet sizes required) and offer a higher probability of a win (i.e. shorter odds). We argue that this lends further support to findings from previous studies (e.g. Xuan & Shaffer, 2009) showing that players chase losses by increasing stakes on more ‘probabilistically conservative’ bets rather than by taking a chance on a longshot. Ultimately, however, this is an area for further investigation potentially through more qualitatively focused analyses with customers of gambling platforms.

Of the three table game categories in this analysis, roulette was the most popular and had the strongest relationship with the markers of harm. The relative higher risk posed online roulette has also been found elsewhere (Dragicevic et al., 2011). We also explored possible differences between live and software versions of table games. The rate of play in live table games is approximately two to three times slower because of the real human interaction involved in taking bets, dealing and collecting cards and the administration of multiple bets from multiple different players for each hand (much like in land-based casinos). As a result of the faster and more continuous game play, we expected the software versions to have a stronger association with the markers of harm. However, in all cases, we found the contrary—greater participation in the live table games was more strongly correlated with markers of harm. It could be that the characteristics of live table games elicit greater trust (outcomes are being determined by real cards and a real dealer rather than an algorithm), create a more realistic and pleasurable environment, and the presence of other players provide opportunities for both social interaction (through chat functionality), and a wider range of bet options such as ‘behind betting’ (betting on another player’s blackjack hand). However, such speculations would need to be subject to further empirical investigation.

More active betting days on ‘less-established sports’ were moderately associated with increased risk. This product’s high correlation with the behavioural marker ‘gambling at unusual hours’ may suggest these risks reflect the availability of ‘less-established sports’ rather than anything inherently riskier about betting on the sport itself. For example, in-play betting on a Premier League soccer game is unlikely to be available late at night for UK players, unlike the Russian table tennis market. Providing a very broad range of sports betting markets from a wide range of different time zones could provide people with gambling problems with a continuous opportunity to place sports bets at any given time, on any given day. As Newall et al. (2021) suggest, a high level of availability in sports betting could also facilitate loss-chasing because they can immediately move on to another sports bet following a loss.

Markers of Harmful Gambling

Although this study did not specifically focus on individual-level risk and draws inferences from the associations observed with higher risk products, it nonetheless adds support to the inclusion of several markers of harm both in future research and in player protection strategies involving customer tracking. These markers include bonus page visits (Catania & Griffiths, 2022 examined how often people asked the operator for bonuses); topping up balances during sessions (Auer & Griffiths, 2022c, f); playing at unusual times of the day (Forrest & McHale, 2022; McAuliffe et al., 2022; Price-Waterhouse Coopers, 2017); and declined deposits (McAuliffe et al., 2022). The first of these, bonus page visits, primarily refers to seeking account top-ups, free bets or free spins all of which may be subject to wagering requirements before account withdrawals are permitted. Theoretically, increased bonus-seeking behaviour may indicate that a player is suffering from withdrawal, has depleted their own money or is attempting to chase losses. In studies of sports betting (e.g. Hing et al., 2018), being exposed to information about additional incentives or special offers has been found to be associated with the subsequent increases in the riskiness of gambling choices and the amount spent. The second, top-ups (i.e. repeat deposits in the same session), could be considered a sign of higher risk gambling because it may reflect loss-chasing (Auer & Griffiths, 2022) and could be indicative of unplanned or unaffordable spending. The third indicator (gambling at unusual hours) is considered important because it may imply that the person is chasing losses or wins (i.e., trying to recover amounts lost or obtain a certain outcome), is finding it difficult to stop gambling or is trying to conceal their gambling from significant others. Such behaviour may also reflect evidence of gambling-related harm in the form of sleep deprivation and its associated adverse effects on health (see Browne et al., 2016).

We looked at two different types of deposit declines. The first of these, deposits that are declined because individuals have no money left in their bank account, may indicate that people are spending large and disproportionate amounts of their disposable income on gambling. While these kinds of declines occur relatively infrequently, they could possibly be indicative of more serious forms of harm (i.e. the type of harm resulting from spending ‘every last penny’ on gambling). However, given the possibility that some people may have hold a different or dedicated account for their gambling (i.e. other disposable income is kept in different accounts), the significance and usefulness of this specific marker should be further investigated. The second type is deposits that are declined by the customer’s bank or payment provider because of suspicious activity which could, instead, be indicating harmful gambling behaviour. This is because activity which may be indicative of fraud (e.g. repeated deposits in quick succession; deposits at unusual times; or increasing, erratic or unusually large sizes of deposits) may also be indicative of loss of control, chasing and other behavioural features of disordered gambling.

Unlike in other studies (e.g. Catania & Griffiths, 2022; Gray et al., 2012), however, we did not find evidence that removing or easing RG settings was useful in differentiating product risks. This may be because this behaviour was rare and its significance is somewhat ambiguous. For example, easing RG settings could reflect an improved ability to assume greater control over the gambling.

Limitations

As with most studies that rely upon operator data, it is important to acknowledge several important limitations. First, this study did not include any independent validation of risk or harm (e.g. PGSI scores) to examine whether the designated markers we used were related to higher risk gambling, although other studies (e.g. Auer & Griffiths, 2022e; Luquiens et al., 2019; Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2017) show behavioural markers such as the number of deposits or gambling at night to be higher amongst people classified as problem gamblers on the PSGI. Second, when making inferences about the comparative risk of different products, it is not possible to determine whether there may be differences in the types of people who choose to gamble on some activities. In other words, if higher risk gamblers gravitate towards certain products (e.g. a late night sports bettor willing to bet on whatever is available), it is not clear whether the associations observed are due to differences in the product’s structural characteristics or the participants who choose those products. However, given that our findings are similar to other studies and slots (the highest ranked product for risk) had the highest participant rate, it seems less likely that the result is solely due to ‘selection’ (i.e. the product is differentially chosen by higher risk gamblers). Slots, in fact, appeared to be popular amongst a wide range of players from those who played very low stakes on rare occasions to those who played larger amounts regularly. Third, it is important to acknowledge the limitation of single product analyses. As Brosowski et al. (2020) have observed, when studying the risk of products to individual gamblers, it is not just the exposure to single activities that is important. Instead, it may be important to examine the combined impact of different products on players. Multiple product use or the ‘breadth’ of gambling may be a stronger risk factor for harm (Gainsbury et al., 2015; LaPlante et al., 2014).

Finally, it is important to point out that these results are based solely on one operator in a single location. These data only give a ‘partial view’ of the individual’s pattern of gambling activity, excluding other online operators and any land-based gambling. Also, results need to be generalized to other countries with caution. Other operators and countries may have different regulatory regimes, marketing and advertising rules and attract different demographic groups.

Conclusions and Implications

Online behaviour analysis has considerable potential to allow insights into the nature of gambling behaviour and whether certain products or structural characteristics are more likely to be associated with gambling-related harm. This work has the potential to offer important regulatory insights that may not be captured by standard risk assessment tools or prevalence or panel studies that rely upon self-report and volunteer samples. Here we confirm that greater engagement in activities identified in the literature as higher risk (shorter event frequencies, in-play sports betting or micro-betting) tends to have stronger associations with important risk indicators. We also extend the literature by showing further risk variations between different sub-categories of sports betting products, most notably, that some types of long-shot, accumulator bets (sharing some characteristics similar to a lottery ticket) pose less risk, whereas combination bets, which involve different permutations of outcomes of the same selection of bets, which increase the probability of a win, at greater financial cost, appear to pose greater risk. This suggests that studies of behaviour or real-time tracking methodologies may have the potential to profile riskier products that emerge in the market, so that responsible gambling measures can be more carefully targeted to those products, or the people who have a high level of engagement in those products. Important future directions in this area include the need for further external validation of proxy measures of harm (e.g. through combining self-report and objective data) as well as a greater focus on within-samples analyses that examine how the behaviour of same individuals differs across products that have structural variations (e.g. Percy et al., 2021). Such analyses have the potential to understand the extent to which variations in risk-related behaviour is related to product as opposed to individual differences. Both regulators, operators and gambling research are likely to continue to benefit from ongoing research in this area as the popularity and accessibility of online gambling options continue to increase.

Data Availability

Due to commercial sensititives, the data is not formally available for wider use, but additional processing of the data-set can be considered by the authors upon request.

Notes

The popularity of sports and events was calculated by number of players betting on a given sport or event over the 6-month observation period.

A variant of poker is also available in the form of a table casino game, with playing against a dealer, rather than playing against other players, being the key difference.

A payment provider or bank may block a deposit if they suspect fraudulent activity. Deposit behaviour which might be indicative fraudulent activity can include repeated deposits in a short period of time, deposits at unusual times, increasing sizes of deposits, deposits which may be very large in size or any other deposit activity which may be considered erratic or out of character. We considered that this marker is relevant because deposit behaviour by at-risk or disordered gamblers could show similar characteristics.

Bonus page visits involve looking for free bets or chips, or money to top-up the account balance which may be given as loyalty bonus or incentive for play. These are often subject to wagering requirements before account withdrawals are permitted.

References

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Voluntary limit setting and player choice in most intense online gamblers: An empirical study of gambling behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(4), 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9332-y

Auer, M. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The use of personalized behavioral feedback for online gamblers: An empirical study. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1406. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01406

Auer, M. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Personalized behavioral feedback for online gamblers: A real world empirical study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(NOV), 1875. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01875

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The impact of personalized feedback interventions by a gambling operator on subsequent gambling expenditure in a sample of Dutch online gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10162-2

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). Attitude towards deposit limits and relationship with their account-based data among a sample of German online slots players. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10155-1

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The relationship between structural characteristics and gambling behaviour: An online gambling player tracking study. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10115-9

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). Using artificial intelligence algorithms to predict self-reported problem gambling with account-based player data in an online casino setting. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10139-1

Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). An empirical attempt to operationalize chasing losses in gambling utilizing account-based player tracking data. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10144-4

Auer, M., Malischnig, D., & Griffiths, M. (2014). Is “pop-up” messaging in online slot machine gambling effective as a responsible gambling strategy? Journal of Gambling Issues, 29(10), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2014.29.3

Auer, M., Hopfgartner, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). The effects of voluntary deposit limit-setting on long-term online gambling expenditure. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0202

Blanco, C., Blaszczynski, A., Clement, R., Derevensky, J., Goudriaan, A. E., Hodgins, D., van Holst, R. J., Ibanez, A., Martins, S., Moersen, C., Molinaro, S., Parke, A., Peren, F., Petry, N., & Wardle, H. (2013). Assessment tool to measure and evaluate the risk potential of gambling products, ASTERIG: A global validation. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 9, 635–642.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., Goulet, A., & Savard, C. (2006). “How much do you spend gambling?” Ambiguities in questionnaire items assessing expenditure. International Gambling Studies, 6(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459790600927738

Braverman, J., & Shaffer, H. J. (2012). How do gamblers start gambling: Identifying behavioural markers for high-risk internet gambling. The European Journal of Public Health, 22(2), 273–278.

Braverman, J., Laplante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., & Shaffer, H. J. (2013). Using cross-game behavioral markers for early identification of high-risk internet gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 868–877. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032818

Browne, M., Langham, E., Rawat, V., Greer, N., Li, E., Rose, J., Rockloff, M., Donaldson, P., Thorne, H., Goodwin, B., Bryden, G., & Best, T. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Brosowski, T., Olason, D. T., Turowski, T., & Hayer, T. (2020). The gambling consumption mediation model (GCMM): A multiple mediation approach to estimate the association of particular game types with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37(1), 107–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09928-3

Catania, M., & Griffiths, M.D. (2021). Understanding online voluntary self-exclusion in gambling: An empirical study using account-based behavioral tracking data. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), art. no. 2000, 1–11 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042000.

Catania, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). Applying the DSM-5 criteria for gambling disorder to online gambling account-based tracking data: An empirical study utilizing cluster analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(4), 1289–1306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10080-9

Challet-Bouju, G., Hardouin, J.-B., Thiabaud, E., Saillard, A., Donnio, Y., Grall-Bronnec, M., & Perrot, B. (2020). Modeling early gambling behavior using indicators from online lottery gambling tracking data: Longitudinal analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e17675. https://doi.org/10.2196/17675

Chen, Z., Doekemeijer, R. A., Noel, X., & Verbruggen, F. (2022). Winning and losing in online gambling: Effects on within-session chasing. PLoS One, 17(8 August), e0273359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273359

Cornish, D. B. (1978). Gambling: A Review of the Literature and its Implications for Policy and Research. Home Office Research Study No. 42.

Delfabbro, P., & Parke, J. (2021). Empirical evidence relating to the relative riskiness of scratch-card gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37(3), 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10033-2

Delfabbro, P., King, D. L., Browne, M., & Dowling, N. A. (2020). Do EGMs have a stronger association with problem gambling than racing and casino table games? Evidence from a decade of Australian prevalence studies. Journal of Gambling Studies, 36(2), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09950-5

Dixon, M. J., Stange, M., Larche, C., Graydon, C., Fuselsang, J., & Harrigan, K. (2017). Dark flow, depression and multiline slot machine play. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33, 1–12.

Dowling, N., Smith, D., & Thomas, T. (2005). Electronic gaming machines: Are they the ‘crack cocaine’ of gambling? Addiction, 100, 33–45.

Dragicevic, S., Tsogas, G., & Kudic, A. (2011). Analysis of casino online gambling data in relation to behavioural risk markers for high-risk gambling and player protection. International Gambling Studies, 11(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2011.629204

Dragicevic, S., Percy, C., Kudic, A., & Parke, J. (2015). A descriptive analysis of demographic and behavioral data from Internet gamblers and those who self-exclude from online gambling platforms. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(1), 105–132.

Forrest, D., & McHale, I. (2022). Patterns of play. Technical report 2: Account data stage. London: GambleAware.

Gainsbury, S. M., & Russell, A. (2015). Betting patterns for sports and races: A longitudinal analysis of online wagering in Australia. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9415-4

Gainsbury, S., Russell, A., & Blaszczyski, A. (2015). Greater involvement and diversity of Internet gambling as a risk factor for problem gambling. The European Journal for Public Health, 25(4), 723–728.

Gainsbury, S. M., Abarbanel, B., & Blaszczynski, A. (2020). The relationship between in-play betting and gambling problems in an Australian context of prohibited online in-play betting. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 574884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.574884

GamGard (2021). Gamgard.com. Accessed 10/1/23.

Gray, H. M., Laplante, D. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2012). Behavioral characteristics of Internet gamblers who trigger corporate responsible gambling interventions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028545

Griffiths, M. D. (1993). Fruit machine gambling: The importance of structural characteristics. Journal of Gambling Studies, 9, 101–120.

Hing, N., Vitartas, P., & Lamont, M. (2017). Understanding persuasive attributes of sports betting advertisements: A conjoint analysis of selected elements. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 658–668.

Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., Thomas, A., & Jenkinson, R. (2019). Wagering advertisements and inducements: Exposure and perceived influence on betting behaviour. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(3), 793–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-09823-y

Hing, N., Russell, A., Rockloff, M., Browne, M., Langham, E., Li, E., Lole, L., Greer, N., Thomas, A., Jenkinson, R., Rawat, V., & Thorne, H. (2018). Effects of wagering marketing on vulnerable adults Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

LaPlante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., & Gray, H. M. (2014). Breadth and depth involvement: Understanding Internet gambling involvement and its relationship to gambling problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033810

Luquiens, A., Dugravot, A., Panjo, H., Benyamina, A., Gaïffas, S., & Bacry, E. (2019). Self-exclusion among online poker gamblers: Effects on expenditure in time and money as compared to matched controls. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224399

McAuliffe, W. H. B., Louderback, E. R., Edson, T. C., LaPlante, D. A., & Nelson, S. E. (2022). Using “markers of harm” to track risky gambling in two cohorts of online sports bettors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 38(4), 1337–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-021-10097-0

Nelson, S. E., Edson, T. C., Louderback, E. R., Tom, M. A., Grossman, A., & Laplante, D. A. (2022). Changes to the playing field: A contemporary study of actual European online sports betting. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00029

Newall, P. S., & Cortis, D. (2021). Are sports bettors biased towards longshots, favorites, or both? A literature review. Risks, 1, 1–9.

Newall, P. W., Russell, A. M., & Hing, N. (2021). Structural characteristics of fixed-odds sports betting products. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10, 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00008

Parke, A., & Parke, J. (2019). Transformation of sports betting into a rapid and continuous gambling activity: A grounded theoretical investigation of problem sports betting in online settings. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(6), 1340–1359.

Parke, J., Parke, A., & Blaszczynski, A. (2016). Key issues in produced-based harm minimisation. London: The Responsible Gambling Trust. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30894.10560

Percy, C., Tsarvenkov, K., Dragicevic, S., Delfabbro, P. H., & Parke, J. (2021). Volatility under the spotlight: Panel regression analysis of online slots player in the UK. International Gambling Studies, 21(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2021.1891273

Perrot, B., Hardouin, J.-B., Grall-Bronnec, M., & Challet-Bouju, G. (2018). Typology of online lotteries and scratch games gamblers’ behaviours: A multilevel latent class cluster analysis applied to player account-based gambling data. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(4), e1746. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1746

Price-Waterhouse Coopers (2017). Remote gambling research. Interim report on Phase II. London: GambleAware.

Russell, A. M. T., Hing, N., Browne, M., Li, E., & Vitartas, P. (2019). Who bets on micro events (microbets) in sports? Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(1), 205–223.

Ukhov, I., Bjurgert, J., Auer, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Online problem gambling: A comparison of casino players and sports bettors via predictive modeling using behavioral tracking data. Journal of Gambling Studies, 37(3), 877–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09964-z

Xuan, Z., & Shaffer, H. (2009). How do gamblers end gambling: Longitudinal analysis of internet gambling behaviors prior to account closure due to gambling related problems. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9118-z

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This paper was prepared as part of a broader product risk project involving Kindred Group which has sponsored the private consulting business Sophro Ltd (JP) and associated sub-contacted work (PD). The work has been undertaken independently without inference or prejudice as would be the case with any other review prepared for an academic journal .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was conducted according to the standards of the NHMRC National Statement on the Ethical Conduct of Research. This study, based on secondary deidentified data, was considered negligible risk.

Conflict of Interest

MC and KC have worked within the gambling industry.

Paul Delfabbro.

I have received funding for research, support for conference travel and speaking engagements from government and non-government research bodies such as AGRI, VRGF, IAGR and the Department of Consumer Affairs, GambleAware/RGT, Gambling Research Australia, Independent Gambling Authority, the ARC, NHMRC, Channel 7 Children’s Foundation and Australian Institute of Criminology. I have conducted paid consultancy work on responsible gambling for regulatory bodies, government, peak bodies and industry groups (e.g., reviews of indicators, standard of player protection, product risk assessment). I acknowledge that many peak research bodies are indirectly funded by industry through levies or contributions.

Jonathan Parke.

Jonathan has received support for research, travel and speaking engagements from a variety of government and non-government sources including AGRI and GambleAware. He has conducted a number of commissioned reports for industry groups. The principal focus of this work has been on harm minimization, responsible gambling and risk associated with different gambling products and features.

Maris Catania.

Maris has been employed by the Kindred Group in roles involving research, player protection, risk assessment and responsible gambling.

Karim Chikh.

Karim has been employed by the Kindred Group as a data analyst and has undertaken work into player protection, risk assessment and responsible gambling.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delfabbro, P., Parke, J., Catania, M. et al. Behavioural Markers of Harm and Their Potential in Identifying Product Risk in Online Gambling. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01060-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01060-8