Abstract

Purpose of Review

Review comprehensive data on rates of toxoplasmosis in Panama and Colombia.

Recent Findings

Samples and data sets from Panama and Colombia, that facilitated estimates regarding seroprevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma and risk factors, were reviewed.

Summary

Screening maps, seroprevalence maps, and risk factor mathematical models were devised based on these data. Studies in Ciudad de Panamá estimated seroprevalence at between 22 and 44%. Consistent relationships were found between higher prevalence rates and factors such as poverty and proximity to water sources. Prenatal screening rates for anti-Toxoplasma antibodies were variable, despite existence of a screening law. Heat maps showed a correlation between proximity to bodies of water and overall Toxoplasma seroprevalence. Spatial epidemiological maps and mathematical models identify specific regions that could most benefit from comprehensive, preventive healthcare campaigns related to congenital toxoplasmosis and Toxoplasma infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The devastating effects of toxoplasmosis—especially the congenital form—are well documented, with a 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) report estimating that congenital toxoplasmosis (CT) creates 1.20 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide [1••, 2, 3]. However, in our primary country of focus—Panama—data on Toxoplasma is sparse, despite several indications of high prevalence. For example, a 1988 study estimated that Panama has one of the highest rates of Toxoplasma infection in Latin America, with seroprevalence of 50% in 10 year olds and 90% in 60 year olds [4•]. Meanwhile, the neighboring countries of Colombia and Costa Rica have estimated seroprevalences of 43–67% and 49–61%, respectively [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. With respect to CT in Panama, annual incidence as estimated by the WHO is 1.8 cases/1000 live births/year, associated with 840 DALYs [3].

A 2014 hospital-based study of Toxoplasma seroprevalence by Montenegro Vasquez et al. (see Part II) helped us define the scope of the problem in Panama, but we sought to better understand regional discrepancies in disease burden, compliance of screening for Toxoplasma among pregnant women (following passage of a mandatory gestational screening law; see part II), and particular risk factors associated with Toxoplasma acquisition.

As such, one priority of our wide-ranging public health project was generating more comprehensive data on rates of toxoplasmosis in Panama (and later, Colombia). We also sought to create spatial epidemiological maps and mathematical models that could help us identify risk factors associated with the disease as it takes place in Central and South America.

Approach

Overview and Chronology

As in the educational initiatives, our understanding of spatial epidemiology and risk factors grew from a foundation of student projects in a growing global health program during that time which has become the Kiphart School of Public Health at The University of Chicago. This involved students from other universities as well. Each student began with a hypothesis, a null hypothesis, and a systematic approach to answering a question. These summer programs provided a foundation for the spatial epidemiology understanding in this work. These studies took place over consecutive summers, each involving at least two undergraduate students, often a medical student and a mentor. This was done in collaboration with an in-country team and grew within each country subsequently. The evolution of this work is shown chronologically in the diagram in the Box.

Box Summary of projects focusing on Toxoplasma epidemiological studies in Panama and Colombia.

Using samples from screening programs for Toxoplasma in Ciudad de Panamá, Panama, and Armenia, Colombia, estimates and trends regarding seroprevalence of antibodies to the parasite were compiled. Screening maps, seroprevalence maps, and risk factor mathematical models were devised based on these data. Most of the materials come from independent investigations conducted by students who were affiliated with global health research programs at the University of Chicago. As more student contributors were graciously invited to work with individuals and institutions in Panama and Colombia, the studies that these students completed and presented became part of a truly international public health initiative, one that quickly involved more institutions and collaborators than many of us had originally conceived. None of these projects would have been possible without the collaboration of numerous US and in-country partners. As such, each contributor’s principal partners are highlighted in supplementary materials that were presented by each of the Chicago students at the end of the summer.

For each student this included abstracts, presentations, papers, and posters at Global Health student programs. These contributions are included in the supplemental materials as the students themselves prepared and presented their work with in-country partners. From each country, parallel manuscripts were prepared utilizing the same data sets. The approach utilized in these studies also has subsequently extended to other countries as well. The approach for each summer is presented first. Then the updates of what the students learned and developed are presented next and discussed.

Screening Rates and Prevalence of T. gondii in Panama (2016–2017)

In 2016, a chart review was conducted on a convenience sample of pregnant women at Hospital Santo Tomas (HST) and Hospital San Miguel Arcángel (HSMA) in Ciudad de Panamá. Information gathered included Toxoplasma screening data, health center/private clinic names, and demographics (age, race, education, literacy). Patient prenatal control cards were requested from outpatients at HST; data were collected anonymously from HST inpatients and all HSMA patients.

Patient addresses were used to map screening rates and T. gondii prevalence in Ciudad de Panamá. Health center information was used to determine which health centers and private clinics provided mandatory screening. Data from patients who had been screened and tested positive for IgM and/or IgG were used to map Toxoplasma prevalence (Fig. 1; Supplement: Wang et al.; Moreira and Pandey et al.)

Sample slides from presentation by Pandey, Moreira, Wang, Rzhetsky, McLeod et al. that details their studies in Panama. One component of their research was a study on the effectiveness of using digital media to teach pregnant women about congenital toxoplasmosis. Pandey and Moreira also created incidence and screening maps for toxoplasmosis in Panama; these maps were based on screening data, IgG/IgM test results, demographic data, and addresses from prenatal control charts. See Supplement for complete presentation

In 2017, a follow-up study was conducted with a convenience sample of pregnant women in HSTs maternity wing. Participants were administered questionnaires asking about additional demographic information (address, hometown size, education, age) and history of exposure to toxoplasmosis risk factors (contact with animals, water source, food hygiene). Five-milliliter blood samples were collected from participants and screened for detection of anti-Toxoplasma IgG/IgM. Data were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests in R. Patient addresses were used to create maps of acute infection and relative screening rates (Supplement: Moossazadeh et al.; Ramirez et al.).

Risk Prediction Model for T. gondii Infection in Panama (2017)

In 2017, prospective assessments of 341 pregnant women at HST’s hospital maternity ward were used to develop a predictive model for risk of exposure to Toxoplasma gondii. Sera from selected patients were tested for anti-Toxoplasma IgG; patients who had been tested for antibodies in the 2 weeks prior to their visit were excluded.

Additionally, seronegative and seropositive patients were screened for factors that included demographic information, contact with wild animals, food hygiene, and food and water sources, all referred to in a 2004 study of toxoplasmosis risk factors by Etheredge et al. [10•]. Past laboratory test results were obtained from patient charts. All statistical tests and analyses were performed in RStudio (Version 3.1.3, Vienna, 2015). See Supplement: Moossazadeh et al.

Spatial Analysis of Toxoplasmosis Screening and Seroprevalence in Panama (Supplement by Raggi et al. 2019)

In 2019, seroprevalence and screening rates in Panama were again mapped using data from previous studies by the University of Chicago and Panama’s Institute of Scientific Research and High Technology Services (INDICASAT). The analysis used both qualitative and quantitative spatial methods, as well as log odds regression. KDE heatmaps used available point data. When possible, data points were condensed into regional data for polygon-based analyses such as natural break and standard deviation heatmaps. Moran’s I cluster analysis was used to search for spatial clustering or outliers.

Locations and outlines of Panama’s hydraulic systems and water basins were found as digitized Tommy Guardia maps by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Similarly, water treatment plants run by Panama’s Institute of Aqueducts and Sewage Systems (IDAAN) were copied from the IDAAN website. Seroprevalence and screening rates of each township in Ciudad de Panamá were then used to make standard deviation, natural break, and Moran’s I cluster maps in Geoda that were overlaid with water system information in QGis (Supplement: Raggi et al.).

Screening Rates, Prevalence, and Risk Factors Related to T. gondii in Colombia (2019)

In 2019, screening rates, seroprevalence, and risk factors for T. gondii infection were mapped using data from Quindío, Colombia. Physicians from the University of Quindío set up temporary clinics providing free eye exams and testing for Toxoplasma infection in the townships of Armenia, La Universal, and Guaduales de la Villa. While waiting to be attended, participants were interviewed about their behavior regarding suspected toxoplasmosis risk factors. Interview questions were used as indicator variables and added to a spreadsheet that included participants’ addresses and exam results. Data were analyzed in RStudio using a log odds linear regression to identify risk factors in each township and in Armenia as a whole. Mapping of T. gondii prevalence and screening involved KDE heatmaps, polygon-based analyses, and Moran’s I cluster analysis (Supplement: Raggi et al.).

Update

Screening Rates and Prevalence of T. gondii in Panama (2016–2017)

Among 665 pregnant women, Moreira and Pandey et al. found that 38.9% had received screening and, of those screened, 21.6% were seropositive for IgG and 5.5% for IgM. IgG seropositivity was found in all age and education groups; indigenous women were more likely to test positive for toxoplasmosis. Screening rates for T. gondii infection in pregnant women at public health centers and private clinics varied from 0 to 100%. Overall, however, private clinics had a much higher screening rate than public health centers.

Logistic regression analysis showed statistically significant longitudinal trends in positive antibody test results, with residents farther to the east of Panama having higher infection rates. Seropositivity rates trended upward around roads and waterways, with three positive cases near the Curundú River. With respect to screening rates, residents to the South had significantly higher chances of being screened than their northern, rural counterparts (Figs. 2, 3, and 4; Supplement: Wang et al.).

Dot and scatter hexbin maps based on Moreira and Pandey et al.’s data on relative screening frequencies of patients in the Ciudad de Panamá metropolitan region. In the top two maps, gray points represent patients not screened for toxoplasmosis, orange points represent patients positive for infection, and blue points represent seronegative patients. Across all four maps, major trends in screening and case frequency include higher frequency of screening from north (more rural) to south (more urban) and higher seropositivity rates along roads and waterways

Maps of screening rates for CT by corregimiento (township) at three different scales, based on Wang et al.’s findings and Moreira and Pandey et al.’s data. Screening rates were calculated using a Bayesian prior of Beta(254, 411). Average screening rate among the townships represented by the women with available data was 38.2%. Townships with much lower or higher than average screening rates are marked with white asterisks

Summary of maps from Figs. 2 and 3, along with a map of toxoplasma seroprevalence by corregimiento (township) at three different scales. Prevalence rates were calculated using a Bayesian prior of Beta(63, 191). Average prevalence of toxoplasmosis among the townships represented by the women with available data was 24.8%. The highest rates of toxoplasmosis were observed in three provinces, shown in very dark red in the highest-resolution map, from west to east: Curundú, Pueblo Nuevo, Pedregal

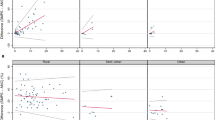

Moossazadeh et al. and Ramirez et al. found that—among 343 pregnant women at HST—19.8% had received screening, and, of those screened, 44% were seropositive for IgG and 2.0% for IgM. Location (longitude, east, Curundu), race (Caucasian), and age (older) were all significantly associated with screening. Chi-square analysis on screening rates and seropositivity in pregnant women in Panama revealed a trend between higher education and screening rates (p = 0.07). However, seropositive women spanned the education level spectrum (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B indicates that pregnant women in urban areas were more likely to be screened, although the difference was not significant.

Summary of findings from Moossazadeh’s study of risk factors and development of a mathematical model for predicting highest-risk areas of Toxoplasma infection in Panama A A strong, but not significant, inverse relationship between highest level attained and screening compliance was found. B Rural-urban comparison showed that pregnant women in urban areas were more likely to be screened; the relationship was not significant. C Ages of IgM + women show that average age of educational; IgM positive women in both 2016–2017 studies was lower than the mean age of their cohorts (25.57 ± 9.03 cf. 27.28 ± 6.23 and 24.43 ± 7.24 cf. 26.59 ± 7.15, respectively). D T. gondii IgG seropositivity rates among pregnant women by maternal age, plotted with age centered around the mean. The curve represents the fit from the logistic regression of IgG status against age squared, with age centered around its mean. The points are shaded according to the number of women at each age, where darker colors signify a greater number of women. E Average education level among pregnant women by maternal age, plotted with age centered around the mean. F T. gondii IgG seropositivity rates among pregnant women by education level. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. G T. gondii IgG seropositivity rates among pregnant women by longitude. Zero degree represents the longitude of Hospital Santo Tomás. H IgG seropositivity rate based on contact or no contact with dogs (both in the street or as pets). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

In both of the studies above, average age of acutely infected women was lower than the average of their respective cohorts (25.57 ± 9.03 cf. 27.28 ± 6.23 and 24.43 ± 7.24 cf. 26.59 ± 7.15, respectively). Figure 5C compares the age distribution of acutely infected women from our 2016 and 2017 studies.

Risk Prediction Model for T. gondii Infection in Panama (2017)

A plot of the proportion of anti-Toxoplasma IgG-positive patients against age exhibits a quadratic curve (Fig. 5D). Education levels were highest at the extreme ends of the age spectrum, while patients around the mean age had a lower mean education level (Fig. 5E). Univariate analyses found (age squared) insignificant when controlling for effects of education (age squared becomes p = 0.07 from p = 0.018). A χ2 analysis of IgG status against education level yielded a significant negative correlation (p = 0.0008) between the two (Fig. 5F). This yielded the following formula, where the coefficient on education is significant (p = 0.0003).

A χ2 analysis of IgG status versus home location (urban or rural) did not yield significant results (p = 0.82). Distance from the hospital, distance from water, and latitude were also not significant in predicting IgG seropositivity (p = 0.98, 0.22, and 0.62, respectively). Longitude was significant (p = 0.004), with seroprevalence decreasing from east to west (Fig. 5G). A logistic regression of IgG status on longitude yields the following formula:

Contact with dogs was the only animal-related factor that showed a positive significant correlation (p = 0.037) with seropositivity (Fig. 5H).

When variables related to diet were analyzed, a logistic regression of pig on seafood yielded an odds ratio of 9.7, and ordinal regressions of raw meat on both pig and seafood yielded odds ratios of 2.2 and 2.4, respectively. A log-linear model of the three-way interaction between pig, seafood, and raw meat was significant (p = 0.012).

While a significant positive correlation was found between hand washing and produce washing (p = 5.7 × 10 − 7), neither variable was significantly associated with IgG seropositivity (p = 0.41 and 0.57, respectively).

Most patients obtained their water from an aqueduct (plumbing), while a few obtained their water from wells, rivers, and rainwater, grouped together as “other.” Water source was not significantly associated with IgG seropositivity (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.56).

Overall, single logistic regressions found only two variables, education (χ2 test, p = 0.0008) and longitude (logistic regression, p = 0.004), had significant and independent correlation with IgG seropositivity. A multiple logistic regression of IgG status against these two variables was run on the 200 patients for whom there was no missing data. Of these 200 patients, 119 were seronegative and 81 were seropositive. Logistic regression yielded the following equation, where both variable coefficients were significant (p = 0.001 and 0.005, respectively):

This equation was used to generate the predicted probability of seropositivity (p) for each of the 200 patients, rounded to the nearest integer (0 or 1) and compared to actual seropositivity status. The model yielded a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.46, a margin of error (ME) of 0.43, and accuracy of 0.68, as well as a false positive rate of 0.11 and a false negative rate of 0.64.

Spatial Analysis of Toxoplasmosis Screening and Seroprevalence in Panama (2019)

Figure 6A shows the distribution and concentration of pregnant women who had been previously screened for toxoplasmosis, and Fig. 6B shows those who had not been screened. The two maps showed distinct distributions, with Fig. 6B having a larger amount of points to the east and the north. The KDE for unscreened individuals also showed clusters around the Pedregal township, with roughly 11 points.

Summary of Raggi’s spatial epidemiological study of toxoplasma screening and seroprevalence rates in Panama. A KDE of previously screened individuals in the province of Panamá (n = 88). B KDE of previously unscreened individuals in the province of Panamá (n = 190). C KDE of previously screened individuals in Panamá Oeste (n = 60). D KDE of previously unscreened individuals in Panamá Oeste (n = 70). E KDE of positive IgG points in the province of Panamá (n = 83). F Aggregated toxoplasmosis prevalence rates based on Panama’s corregimientos, overlaid on Panama’s water systems

Figures 6C and D show the distribution of pregnant women who had been screened and not screened, respectively, in the province of Panamá Oeste. A cluster of screened individuals was found in the town of Nuevo Arraiján. In addition, almost every point in the township of Veracruz region, and on much of the coast in general, was marked as being from an unscreened individual. The distribution of screened individuals also closely followed the location of the Arraiján-Chorrera Freeway (the red line displayed on the map), while the unscreened distribution was more scattered (Fig. 6E).

The natural break map focusing on water sources in Panamá identified clusters of seropositive patients around water sources, as can be seen by the two large red sections both immediately to the right of the Panama Canal and at the far right of the map (Fig. 6F). Seroprevalence also trended upward from west to east.

Screening Rates, Prevalence, and Risk Factors Related to T. gondii in Colombia (2019)

The only notable association among the variables in the Armenia study was that between Toxoplasma seropositivity and use of unboiled water/drinking tap water (Fig. 7A).

Summary of mapping studies from Colombia. A Scatterplot matrix of all variables used in the Armenia study. B Statistically significant variable relationships and their p value ranges for the entire population surveyed. C Heat map showing the distribution of all cases of CT that went untreated in Quindío (n = 23). D Heat map showing cases of CT that received prenatal treatment in Quindío (n = 21). E Heat map of relative frequencies of cats negative for Toxoplasma, as determined by the University of Quindío (n = 109). F Heat map of relative frequency of cats positive for Toxoplasma, as determined by the University of Quindío (n = 25)

Among participants from La Universal, no variables except for age were significantly associated with IgG antibodies (Fig. 7B), and this significant relationship was lost in the multivariable linear regression. In Guaduales de la Villa, the habits of drinking bottled water and eating undercooked meat were negatively associated with infection. Variable representing eating undercooked meat was just coded “yes” as 1 and “no” as 0. The outcome variable was 1 if they were marked as positive in the IgG column of the dataset. This analyisis used a logistic regression in R with seropositivity as the outcome and all variables used as covariates. In this model, undercooked meat had a p value of 0.034. In an analysis where undercooked meat is the only predictor and other variables are not accounted for. However, it was not significant with a p value of 0.06. The total model as better adjusted for the effects of the other variables and the analyses in context of each other suggest that oocyst contamination of water is the most important source of infection, with both variables perhaps influenced by socioeconomic status Additionally, ocular lesions associated with Toxoplasma only occurred in people with IgG antibodies.

CT cases were mapped based on whether mothers had received prenatal treatment (Fig. 7C and D). Guaduales de la Villa showed relatively high rates of prenatal treatment within Armenia. Of the 8 points around that community, 7 had been treated (87.5%); meanwhile, only 21 of the 44 points with known treatment status in Armenia had received treatment (47.7%).

Figures 7E and F show the distribution of all cats in Armenia and distribution of cats based on Toxoplasma infection status. No significant relationship was found between the spatial distributions of IgG-negative and IgG-positive cats in Armenia.

Discussion

Identifying specific higher-risk areas for toxoplasmosis enables more comprehensive prevention strategies that are tailored to sources of this disease. In Panama, our efforts to gather data for this end began with the 2014 HdN report, which estimated that seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in Ciudad de Panamá could be as high as 50%. Later studies in 2016 and 2017 found high overall prevalence among pregnant women (about 22% and 44% IgG seropositivity, respectively), with consistent patterns of regional variability. For example, within the capital metropolitan area, townships with considerable poverty (such as Curundú) reached up to 24 times the average prevalence in Ciudad de Panamá. These findings were consistent with previous research that had associated greater seropositivity with living conditions that included dirt floors, open doors, and insect exposure [4•]. Both an increase in prevalence from western to eastern Panama and higher rates of disease in indigenous populations (although not to a statistically significant degree) were found in an initial retrospective study, a follow-up prospective study, and a longer-term aggregate study of 3500 women that used more sophisticated spatial epidemiology methods. More recent research, some of which has also examined regional seroprevalence in cats and dogs, has corroborated the trends found in our initial studies [11•, 12, 13•].

Out of several other findings, we noticed a strong association between seropositivity and proximity to water sources such as the Panama Canal; we are still investigating this correlation. Additionally, prevalence is high at the confluence of the Bayano and Mamoni rivers in the area of the Chepo water processing plant. From many possible risk factors, proximity to water would not have come to our attention if not for spatial epidemiological work in Colombia, a country where treatment for CT has reduced severe disease over the past 5 years and where water has been identified as a major route of Toxoplasma transmission [14•, 15]. Our study of risk factors in Quindío emphasized the correlation between proximity to bodies of water and issues such as congenital infection, retinal disease, and rates of lymphadenopathy related to toxoplasmosis. Recent studies have confirmed the importance of water to transmission of Toxoplasma in Colombia [16•]. Future studies in either Panama or Colombia should also investigate well water, which was found to be a risk factor in a recent study of agrarian populations in Morocco [17•].

Conclusion

Overall, these spatial epidemiological studies have helped identify populations and geographic areas in Panama and Colombia where efforts to screen pregnant women for Toxoplasma and to provide prompt treatment to prevent CT might have the greatest relative impact. Furthermore, this work has also informed Moossazadeh’s mathematical models of infection risk, which could guide future interventions in cases where detailed epidemiological data are not available. Although our goal is to make our screening, treatment, and education programs available throughout both countries of focus, identifying the highest-risk areas is an important, practical step in this process.

Change history

06 November 2022

Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• McLeod R, Lykins J, Noble AG, Rabiah P, Swisher C, Heydemann P, McLone D, Frim D, Withers S, Clouser F, Boyer K. Management of congenital toxoplasmosis. Curr Ped Rep. 2014;2(3):166–94. Describes presentation of congenital toxoplasmosis and approach to management of the disease in the United States, including definition of known risk factors, epidemiology, and care.

McLeod R, Kieffer F, Sautter M, Hosten T, Pelloux H. Why prevent, diagnose and treat congenital toxoplasmosis? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:320–44.

Torgerson PR, Mastroiacovo P. The global burden of congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(7):501–8.

• Sousa OE, Saenz RE, Frenkel JK. Toxoplasmosis in Panama: a 10-year study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38(2):315–22. Provides an early description of epidemiology of Toxoplasma infection in Panama.

Pappas G, Roussos N, Falagas ME. Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis. Int J for Parasitol. 2009;39:1385–94.

Rosso F, Les JT, Agudelo A, Villalobos C, Chaves JA, Tunubala GA, Messa A, Remington JS, Montoya JG. Prevalence of infection with Toxoplasma gondii among pregnant women in Cali, Colombia, South America. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78(3):504–8.

Castro AT, Congora A, Gonzalez ME. Toxoplasma gondii antibody seroprevalence in pregnant women from Villavicencio. Colombia Orinoquia. 2008;12:91–100.

Barrera AM, Castiblanco P, Gomez-Marin JE, Lopez MC, Ruiz A, Moncada L, Reyes P, Corredor A. Toxoplasmosis adquirida durante el embarazo, en el Instituto Materno Infantil en Bogotá. Rev Sal Púb. 2002;4(3):286–93.

Zapata M, Reyes L, Holst I. Disminución en la prevalencia de anticuerpos contra Toxoplasma gondii en adultos del valle central de Costa Rica. Parasitol Latinoam. 2005;60:32–7.

• Etheredge GD, Michael G, Muehlenbein MP, Frenkel JK. The roles of cats and dogs in the transmission of Toxoplasma infection in Kuna and Embera children in eastern Panama. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;16(3):176–86. Evaluates role of exposure to cats and dogs as risks for children within indigenous populations in eastern Panama to be seropositive for Toxoplasma.

• Rengifo-Herrera C, Pile E, Garcia A, Perez A, Perez D, Nguyen FK, De la Guardia V, McLeod R, Caballero Z. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in domestic pets from metropolitan regions of Panama. Parasite. 2017;https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2017009. Maps prevalence of serum antibody to Toxoplasma in cats and dogs in different regions of Panama.

Fabrega L, Restrepo CM, Torres A, Smith D, Chan P, Perez D, Cumbrera A, Caballero Z. Frequency of Toxoplasma gondii and risk factors associated with the infection in stray dogs and cats of Panama. Microorganisms. 2020;https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060927.

• Flores C, Villalobos-Cerrud D, Borace J, McLeod R, Fábrega L, Norero X, Sáez-Llorens X, Moreno MR, Restrepo CM, Llanes A, Quijada M, De Guevara ML, Guzán G, De la Guardia V, García A, Wong D, Soberon M, Caballero Z. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with T. gondii infection in pregnant women and newborns from Panama. Pathogens; June 8 2021; in press. Analyzes seropositivity by regions in Panama for large numbers of pregnant women cared for at Hospital Santo Tomás, demonstrating high seroprevalence in pregnant women and several risk factors. This paper also provides an overview to which the present study contributed.

El Bissati K, Levigne P, Lykins J, Adlaoui EB, Barkat A, Berraho A, Laboudi M, El Mansouri B, Ibrahimi A, Rhajaoui M, Quinn F, Murugesan M, Seghrouchni F, Gomez-Marin JE, Peyron F, McLeod R. Global initiative for congenital toxoplasmosis: an observational and international comparative clinical analysis. Emerg Micr & Inf. 2018;7:165.

Triviño-Valencia J, Lora F, Zuluaga JD, Gomez-Marin JE. Detection by PCR of pathogenic protozoa in raw and drinkable water samples in Colombia. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1789–97.

• Gómez-Marin JE, Muñoz-Ortiz J, Mejía-Oquendo M, Arteaga-Rivear JY, Rivera-Valdivia N, Bohórquez-Granados MC, Velasco-Velásquez S, Castaño-de-la-Torre G, Acosta-Dávila JA, García-López LL, Torres-Morales E, Vargas M, Valencia JD, Celis-Giraldo D, de-la-Torre A. High frequency of ocular toxoplasmosis in Quindío, Colombia and risk factors related to the infection. Heliyon. 2021;7:e06659. Re-emphasizes the critical role water plays in transmission of Toxoplasma in Colombia.

• El Mansouri B, Amarir F, Peyron F, Adlaoui AB, Piarroux R, El Abassi M, Lykins J, Nekkal N, Bouhlal N, Makkaoui K, Barkat A, Lyaghfouri A, Zhou Y, Rais S, Daoudi F, Elkoraichi I, Zekri M, Nezha B, Hajar M, Rhajaoui M, Sadak A, Limonne D, McLeod R, El Bissati K. Emerg Microbes Infect. June 8 2021; in press. Emphasizes the association of seropositivity for Toxoplasma with lower socioeconomic status and more frequent use of well water in a high-prevalence population in Morocco.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following organizations and people for their financial, logistical, and/or technical support during our work on this project.

Panama: Thanks to the Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (SENACYT), the Sistema Nacional de Investigación (SNI), the Institute for Scientific Research and High Technology Services of Panama (INDICASAT), Hospital del Niño, Hospital Santo Tomás, and Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. Special thanks to the medical staff of the high-risk pregnancy and infectious disease wings of Hospital Santo Tomás, especially Aris Caballero de Mendieta, Susana Frías, Dario Beneditto, Edwin Ortiz, Carlos Moreno, Ana Belen Arauz, Monica Pachar, Eyra Garcia, as well as to the nurses for all their logistical support.

We thank little Henry Arosemena, who was the impetus for starting the program in Panama, and the Arosemena family for their support of educational initiatives in Panama.

Colombia: Thanks to the Grupo de Investigación en Parasitología Molecular (GEPAMOL) at the University of Quindío, to Richard James Orozco González, and to Hospital del Sur and Hospital San Juan de Dios in Armenia, Colombia.

USA: Thanks to Dr. Brian Callender, Dr. Jeanne Farnan, Dr. Olofunmilayo Olopade, Absera Melaku, MPH, Kristyna Hulland, MS, Dr. Susan Duncan, and Dr. John Schneider for making summer research possible through the Summer Research Program at the Pritzker School of Medicine at UChicago. We appreciate Aaron Ponsler’s suggestion at a Thrasher Foundation site visit at Stanford University that the LDBio could do the most good if it were cleared by the FDA and waived by CLIA.

We thank all those in the National Collaborative Chicago Based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study (NCCCTS) who helped build programs in the USA. We especially thank the many families who participated in and encouraged these initiatives and their primary care physicians. We thank all those who traveled to Springfield to begin these in the USA, recognizing the importance this would have for their families.

We thank and gratefully acknowledge Kristen Wroblewski MS and Theodore Karrison PhD for their many contributions.

We thank those who worked with the NCCCTS in the earlier years including Marilyn Mets, William Mieler, Michael Grassi, Michael Kip, Hassan Shah, Cariina Yang, Delilah Burrowes, John McConnell, Sarah Keedy, Shaolin Yang, Minje Wu, Lisa Lu, Dushyant Patel, Diane Patton, Vicky Aithchison, Holly McGinnis, Randee Estes, Michael Kirisits, Adrian Esquoal,Toria Trendler, Simone Cesar, Jessica Coyne, Diana Chamot, Lazlo Stein, Jack Remington, Raymund Ramirez, Daniel Lee, Veena Arun, Laura Phan, Daniel Johnson, Adil Javed Michael Kirisits, Douglas Mack, Lazlo Stein, and others as reflected in the author lists in Refs. 3–50. Their contributions to the initial phases of this work were substantial.

Thanks to those working with us to establish gestational screening for perinatal infections and to develop and test WHO-compatible POC tests in the USA, France, and Morocco, Mohamed Rhajaoui, Amina Barkat, Hua Cong, and Bo Shiun Lai.

France/Austria: Many thanks to our French and Austrian colleagues, who paved the way to understanding the importance of prompt gestational screening, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis.

Additionally, we thank Shaun Carey, James Lynch, Millie Malekar, others in the IRB office; Jim Rago and Sam Campbell for photography; David Goodwin, Steven Gitterman, Colin Shepard and Ribhi M. Shawar for their guidance with FDA processes, NIH DMID Program; Michael Gottlieb, F. Lee Hall, Stephanie James, and John Rogers for many suggestions. Additionally, Morocco Group colleagues including Mohamed Rhajaoui working alongside and with us and help and support in implementing prenatal screening for toxoplasmosis in Morocco*. Iris Ramirez for contribution to screening. Tom Lint for assistance with many aspects of the study.

Special thanks to the participant families and their physicians without whom this NCCCTS could not have been performed.

Funding

Additional thanks for funding from the Jeff Metcalf Internship Program, the Margaret P Thorp Scholarship Fund, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for their Medical Student Award, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for their Grant #T35DK062719-30, the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene for their Benjamin H. Kean Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health for their Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Grant #R01 AI2753, the Thrasher Research Fund for their E.W. “Al” Thrasher Award, and the Kiphardt Global–Local Health Seed Fund Award, University of Chicago. Senacyt, Hyatt Hotels Foundation.

We are grateful to Toxoplasmosis Research Institute, Taking out Toxo, Network for Good, the Conwell Mann Family Foundation, The Rodriguez family, The Samuel family and Running for Fin, the Morel, Rooney, Mussalami, Kapnick, Taub, Engel, Harris, Quinn, Drago families, Pritzker, and the Hyatt Hotels, Foundation, United, American, Southwest, Braniff and other airlines.

We gratefully acknowledge the Susan and Richard Kiphart Family Foundation for providing funding for open access charges.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mariangela Soberón Felín, Kanix Wang, Catalina Raggi, Aliya Moreira, Abhinav Pandey, Andrew Grose, Zuleima Caballero, Claudia Rengifo-Herrera, Davina Moossazadeh, Catherine Castro, José Luis Sanchez Montalvo, Karen Leahy, Ying Zhou, Fatima Alibana Clouser, Maryam Siddiqui, Nicole Leong, Perpetua Goodall, Mahmoud Ismail, Monica Christmas, Stephen Schrantz, Ximena Norero, Dora Estripeaut, David Ellis, Kevin Ashi, Samantha Dovgin, Ashtyn Dixon, Xuan Li, Ian Begeman, Sharon Heichman, Joseph Lykins, Delba Villalobos-Cerrud, Lorena Fabrega, Connie Mendivil, Mario R. Quijada, Silvia Fernández-Pirla, Digna Wong, Mayrene Ladrón de Guevara, Carlos Flores, Jovanna Borace, Anabel García, Natividad Caballero, Maria Theresa Moreno de Saez, Michael Politis, Stephanie Ross, Mimansa Dogra, Vishan Dhamsania, Nicholas Graves, Marci Kirchberg, Kopal Mathur, Ashley Aue, Carlos M. Restrepo, Alejandro Llanes, German Guzman, Arturo Rebollon, Kenneth Boyer, Peter Heydemann, A. Gwendolyn Noble, Charles Swisher, Peter Rabiah, Shawn Withers, Teri Hull, Chunlei Su, Paul Latkany, Ernest Mui, Daniel Vitor Vasconcelos-Santos, Alcibiades Villareal, Ambar Perez, Carlos Andrés Naranjo Galvis, Mónica Vargas Montes, Nestor Ivan Cardona Perez, Morgan Ramirez, Cy Chittenden, Edward Wang, Laura Lorena Garcia-López, Juliana Muñoz-Ortiz, Nicolás Rivera-Valdivia, María Cristina Bohorquez-Granados, Gabriela Castaño de-la-Torre, Guillermo Padrieu, Daniel Celis-Giraldo, John Alejandro Acosta Dávila, Elizabeth Torres, Manuela Mejia Oquendo, José Y. Arteaga-Rivera, Dan Nicolae, Andrey Rzhetsky, Nancy Roizen, Eileen Stillwaggon, Larry Sawers, Francois Peyron, Martine Wallon, Emanuelle Chapey, Pauline Levigne, Carmen Charter, Migdalia De Frias, Jose Montoya, Cindy Press, Raymund Ramirez, Despina Contopoulos-Ioannidis, Yvonne Maldonado, Oliver Liesenfeld, Carlos Gomez, Kelsey Wheeler, Samantha Zehar, James McAuley, Denis Limonne, Raphael Piarroux, Vera Tesic, Kathleen Beavis, Ana Abeleda, Mari Sautter, Bouchra El Mansouri, Adlaoui El Bachir, Fatima Amarir, Kamal El Bissati, Michael Grigg, Alejandra de-la-Torre, Gabrielle Britton, Jorge Motta, Eand duardo Z. Ortega-Barria, Jorge Gomez-Marin, Osvaldo Reyes, Xavier Saez-Llorens, and Rima McLeod contributed to collection and/or analysis of primary data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Deceased: Charles Swisher, Eileen Stillwaggon, and Paul Meier.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on International Health.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Felín, M.S., Wang, K., Raggi, C. et al. Building Programs to Eradicate Toxoplasmosis Part III: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Curr Pediatr Rep 10, 109–124 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-022-00265-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-022-00265-0