Abstract

Purpose

Many caregivers take paid and/or unpaid time off work, change from full-time to part-time, or leave the workforce. We hypothesized that cancer survivor-reported material hardship (e.g., loans, bankruptcy), behavioral hardship (e.g., skipping care/medication due to cost), and job lock (i.e., staying at a job for fear of losing insurance) would be associated with caregiver employment changes.

Methods

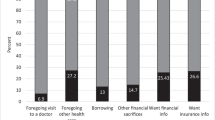

Adult cancer survivors (N = 627) were surveyed through the Utah Cancer Registry in 2018–2019, and reported whether their caregiver had changed employment because of their cancer (yes, no). Material hardship was measured by 9 items which we categorized by the number of instances reported (0, 1–2, and ≥ 3). Two items represented both behavioral hardship (not seeing doctor/did not take medication because of cost) and survivor/spouse job lock. Odds ratios (OR) were estimated using survey-weighted logistic regression to examine the association of caregiver employment changes with material and behavioral hardship and job lock, adjusting for cancer and sociodemographic factors.

Results

There were 183 (29.2%) survivors reporting their caregiver had an employment change. Survivors with ≥ 3 material hardships (OR = 3.13, 95%CI 1.68–5.83), who skipped doctor appointments (OR = 2.88, 95%CI 1.42–5.83), and reported job lock (OR = 2.05, 95%CI 1.24–3.39) and spousal job lock (OR = 2.19, 95%CI 1.17–4.11) had higher odds of caregiver employment changes than those without these hardships.

Conclusions

Caregiver employment changes that occur because of a cancer diagnosis are indicative of financial hardship.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Engaging community and hospital support for maintenance of stable caregiver employment and insurance coverage during cancer may lessen survivors’ financial hardship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Utah Cancer Registry but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used with permissions for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Utah Cancer Registry.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Mariotto AB, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–28.

Nipp RD, et al. Financial Burden in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol : Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3474–81.

Zafar SY, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–90.

Banegas MP, et al. The social and economic toll of cancer survivorship: a complex web of financial sacrifice. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract. 2019;13(3):406–17.

Smith GL, et al. Financial Burdens of Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw : JNCCN. 2019;17(10):1184–92.

Altice CK, et al. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2).

Nijboer C, et al. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer. 2001;91(5):1029–39.

Kent EE, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–95.

Longacre ML, Weber-Raley L, Kent EE. Cancer Caregiving While Employed: Caregiving Roles, Employment Adjustments, Employer Assistance, and Preferences for Support. J Cancer Educ. 2021;36(5):920–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01674-4.

de Moor JS, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract. 2017;11(1):48–57.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I. Returning to work after cancer: Survivors’, caregivers’, and employers’ perspectives. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):792–8.

Mosher CE, et al. Economic and social changes among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):819–26.

Kirchhoff AC, et al. “Job Lock” Among Long-term Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):707–11.

Small Health Statistical. In: Utah Automated Geographic Reference Center. https://gis.utah.gov/data/health/health-small-statistical-areas/. Accessed 1/11/2022

Office of Public Health Assessment: Center for Health Data and Informatics. 2021. https://opha.health.utah.gov/. Accessed 1 Jan 2022.

Utah Cancer Action Network, 2016–2020 Utah comprehensive cancer prevention and control plan. 2016. Avaialble at: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/publications/cancer/ccc/utah_ccc_plan-508.pdf. Accessed 1/11/2022.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdfques/2017_BRFSS_Pub_Ques_508_tagged.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021.

Park ER, et al. Assessing Health Insurance Coverage Characteristics and Impact on Health Care Cost, Worry, and Access: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1855–8.

Fair D, et al. Material, behavioral, and psychological financial hardship among survivors of childhood cancer in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2021;127(17):3214–3222.

Dillman DA. The promise and challenge of pushing respondents to the web in mixed-mode surveys. In: Survey Methodology, Statistics Canada. 2017. 120–001-x (43): No 1. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-001-x/2017001/article/14836-eng.htm. Accessed 1/11/2022.

de Moor JS, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):48–57.

Altice CK, et al. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109(2):djw205.

Jones SMW, Nguyen T, Chennupati S. Association of Financial Burden With Self-Rated and Mental Health in Older Adults With Cancer. J Aging Health. 2020;32(5–6):394–400.

Geng HM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e11863.

Kent EE, et al. The Characteristics of Informal Cancer Caregivers in the United States. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(4):328–32.

Rashad I, Sarpong E. Employer-provided health insurance and the incidence of job lock: a literature review and empirical test. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(6):583–91.

Map of current cigarette use among adults. In: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/cigaretteuseadult.html. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Mean age by state 2022. In: World Population Review. 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/median-age-by-state. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Krogstad J. Hispanics have accounted for more than half of total U.S. population growth since 2010. In: Pew Research Cancer. 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/10/hispanics-have-accounted-for-morethan-half-of-total-u-s-population-growth-since-2010. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Bankruptcy filing trends in the United States. American Bankruptcy Institute. 2021. https://abiorg.s3.amazonaws.com/Newsroom/State_Filing_Trends/2020_TRENDS_NATIONAL.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

2015-2019 Women in the Workforce: State of Utah. In. Department of workforce services. 2021. https://jobs.utah.gov/wi/data/library/laborforce/womeninwf.html. Accessed 26 June 2021.

Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. In: AARP Family Caregiving & The National Alliance for Caregiving. 2020. https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving-in-the-us-2020. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Banegas MP, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):54–61.

Finn B. Millennials: The emerging generation of family caregivers. In: AARP Public Policy Institute. 2018. https://www.aarp.org/ppi/info-2018/millennialfamily-caregiving.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80.

Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;100:63–75.

Sherwood PR, et al. Predictors of employment and lost hours from work in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):598–605.

Mudrazija S. Work-Related Opportunity Costs Of Providing Unpaid Family Care In 2013 And 2050. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(6):1003–10.

Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Nov 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396401. Accessed 11 Jan 2022.

Funding

This study was supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, Cooperative Agreement No. NU58DP006320. The Utah Cancer Registry is also funded by the National Cancer Institute's SEER Program, Contract No. HHSN261201800016I, with additional support from the University of Utah and Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Dr. Warner is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute under award T32CA078447.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Survey design, material preparation, and data collection were performed by Morgan Millar, Sandra Edwards, Marjorie Carter, Carol Sweeney, and Anne Kirchhoff. Data analysis was performed by Echo Warner and Brian Orleans. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Echo Warner and Perla Vaca Lopez and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Utah Department of Health institutional review board.

Consent to participate

Participants who completed the consent process provided free-given, informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warner, E.L., Millar, M.M., Orleans, B. et al. Cancer survivors’ financial hardship and their caregivers’ employment: results from a statewide survey. J Cancer Surviv 17, 738–747 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01203-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01203-1