Abstract

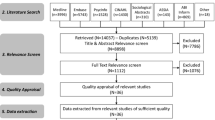

Purpose Construction remains one of the most hazardous and disabling industries worldwide. This scoping review was completed to identify barriers and facilitators related to return-to-work (RTW) after work injury in the construction industry and gaps in the literature. Methods We searched ten databases from 1990 to 2020 for academic and grey literature. Two independent reviewers screened citations for inclusion. One team member charted the data and a second team member reviewed the coding. Articles were included if they identified any barriers or facilitators to RTW in the construction industry. The findings were synthesized into overarching themes. Results Our search identified 6706 articles for screening, with 22 articles included in the final sample. Three articles used qualitative methods, while the remaining articles were quantitative. The majority of articles were from North America and published in academic journals. Overall, findings are organized under seven main themes: worker sociodemographic characteristics; injury characteristics; worker motivation; workplace goodwill; modified work and disability management; work disability systems; and access to healthcare. Some barriers and facilitators are more relevant to the construction industry compared with the general working population. Conclusions: The findings suggest that accommodations are possible for this industry but barriers still exist in identifying suitable work. More research is needed to investigate the role of union involvement, work disability management systems, gender, and organizational characteristics, such as multiple worksites, in relation to RTW in the construction industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Brown S, Harris W, Brooks R, Xiuwen D. Fatal injury trends in the construction industry [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.cpwr.com/wp-content/uploads/DataBulletin-February-2021.pdf

Brown S, Brooks R, Dong X. Nonfatal injury trends in the construction industry [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.cpwr.com/wp-content/uploads/DataBulletin-December2020.pdf

Eurostat. Accidents at work statistics, 2017 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Accidents_at_work_-_statistics_by_economic_activity

Safe Work Australia. Key work health and safety statistics, Australia 2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/statistical-reports/key-work-health-and-safety-statistics-australia-2021

WorkSafeBC. Provincial overview [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/worksafebc/viz/Provincialoverview/Didyouknow

Winge S, Albrechtsen E. Accident types and barrier failures in the construction industry. Saf Sci. 2018;1(105):158–166.

Swuste P, Frijters A, Guldenmund F. Is it possible to influence safety in the building sector?: A literature review extending from 1980 until the present. Saf Sci. 2012;50(5):1333–1343.

Boschman JS, Van Der Molen HF, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Musculoskeletal disorders among construction workers: a one-year follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):196.

McLeod CBC, Macpherson RAR, Quirke W, Fan J, Amick III BCBC., Mustard CACA, et al. Work disability duration: a comparative analysis of three Canadian provinces. Vancouver, BC; 2017.

Collie A, Lane TJ, Hassani-Mahmooei B, Thompson J, McLeod C. Does time off work after injury vary by jurisdiction? A comparative study of eight Australian workers’ compensation systems. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010910.

Stice DC, Moore CL. A study of the relationship of the characteristics of injured workers receiving vocational rehabilitation services and their depression levels. J Rehabil. 2005;71(4):12.

Dong XS, Wang X, Largay JA, Sokas R. Long-term health outcomes of work-related injuries among construction workers-findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(3):308–318.

Carnide N, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Breslin FC, Severin CN, et al. Course of depressive symptoms following a workplace injury: a 12-month follow-up update. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(2):204–215.

Senthanar S, MacEachen E, Lippel K. Return to work and ripple effects on family of precariously employed injured workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30(1):72–83.

Proctor TJ, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD. Unremitting health-care-utilization outcomes of tertiary rehabilitation of patients with chronic musculoskeletal disorders. J Bone Jt Surg A. 2004;86(1):62–69.

Waehrer GM, Dong XS, Miller T, Men Y, Haile E. Occupational injury costs and alternative employment in construction trades. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(11):1218–1227.

Passmore D, Chae C, Borkovskaya V, Baker R, Yim JH. Severity of U.S. construction worker injuries 2015–2017. E3S Web Conf. 2019;97:2015–2017.

Shafique M, Rafiq M. An overview of construction occupational accidents in Hong Kong: a recent trend and future perspectives. Appl Sci. 2019;9(10):2069.

Kines P, Spangenberg S, Dyreborg J. Prioritizing occupational injury prevention in the construction industry: Injury severity or absence? J Saf Res. 2007;38(1):53–58.

Rivara FP, Thompson DC. Prevention of falls in the construction industry: evidence for program effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4 SUPPL. 1):23–26.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1291–1294.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Neuhauser F. Modified work and return to work: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 1998;8(2):113–139.

Franche R-L, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–631.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E, Cullen K, Frank J, et al. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:257–269.

Krause N, Frank JW, Dasinger LK, Sullivan TJ, Sinclair SJ. Determinants of duration of disability and return-to-work after work-related injury and illness: challenges for future research. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(4):464–484.

Gensby U, Labriola M, Irvin E, Amick BC, Lund T. A classification of components of workplace disability management programs: results from a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24:220–241.

Andersen LP, Kines P, Hasle P. Owner attitudes and self reported behavior towards modified work after occupational injury absence in small enterprises: a qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(1):107–121.

Casso G, Cachin C, Van Melle G, Gerster JC. Return-to-work status 1 year after muscle reconditioning in chronic low back pain patients. Jt Bone Spine. 2004;71(2):136–139.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Pugliese D, Majesky G, Kramer D, Steenstra I, et al. Buddies in bad times? The role of co-workers after a work-related injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(3):438–449.

Gillen M. Injuries from construction falls. Functional limitations and return to work. AAOHN J. 1999;47(2):65–73.

Kucera KL, Lipscomb HJ, Silverstein B. Medical care surrounding work-related back injury claims among Washington State Union Carpenters, 1989–2003. Work. 2011;39(3):321–330.

Lingard H, Saunders A. Occupational rehabilitation in the construction industry of Victoria. Constr Manag Econ. 2004;22(10):1091–1101.

Schneider S, Vi P. Ergonomics: promoting early return to pre-injury job using a rebar trying machine. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2005;2(5):D34–D37.

Schwatka NV, Butler LM, Rosecrance JC. Age in relation to worker compensation costs in the construction industry. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(3):356–366.

Winter J, Issa MHH, Quaigrain R, Dick K, Regehr JDD. Evaluating disability management in the Manitoban construction industry for injured workers returning to the workplace with a disability. Can J Civ Eng. 2016;43(2):109–117.

Young AE, Choi YS. Work-related factors considered by sickness absent employees when estimating timeframes for returning to work. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0163674.

Anderson NJ, Bonauto DK, Adams D. Psychiatric diagnoses after Hospitalization with work-related burn injuries in Washington State. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32(3):369–378.

Burdorf A, Naaktgeboren B, Post W. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal sickness absence and return to work among welders and metal workers. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55(7):490–495.

Durand M-J, Berthelette D, Loisel P, Imbeau D. Validation of the programme impact theory for a work rehabilitation programme. Work. 2012;42(4):495–505.

Hankins AB, Reid CA. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule of the return-to-work status of injured employees in Minnesota. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(3):599–616.

Kucera KL, Lipscomb HJ, Silverstein B, Cameron W. Predictors of delayed return to work after back injury: a case-control analysis of union carpenters in Washington State. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(11):821–830.

SafeManitoba. Analysis of Disability Management Practices in the Construction Sector [Internet]. Manitoba, Canada; 2010. Available from: https://www.safemanitoba.com/PageRelatedDocuments/resources/disability_management_practicesin_the_construction_sector.pdf

Welch LS, Hunting KL, Nessel-Stephens L. Chronic symptoms in construction workers treated for musculoskeletal injuries. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36(5):532–540.

Cocker F, Sim MR, Kelsall H, Smith P. The association between time taken to report, lodge, and start wage replacement and return-to-work outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(7):622–630.

Issa MH, Quaigrain RA. Evaluating the Accessibility of the Manitoban Construction Industry to Physically Disabled Construction Workers and its Relation to Safety Performance [Internet]. Winnpeg, Manitoba, Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.wcb.mb.ca/sites/default/files/files/FinalReport-EvaluatingtheAccessibilityoftheManitobanConstructionIndustry.pdf

Quaigrain RA. Evaluating Disability Management in Construction Using Maturity Modelling and Metrics and its Relation to Safety Performance. University of Manitoba; 2019.

Quaigrain RA, Issa MH. Construction disability management maturity model: case study within the Manitoban construction industry. Int J Work Heal Manag. 2021;14(3):274–291.

Schofield K, Ryan AD, Dauner KN. Comparing disability and return to work outcomes between alternative and traditional workers’ compensation programs. Am J Ind Med. 2019;62(9):755–765.

Canada I. Canadian industry statistics (CIS): Construction industry (NAICS 23) [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/scr/app/cis/summary-sommaire/23

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Private sector construction industry (Ca. number 8772.0) [Internet]. Canberra, Australia; 2013. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/8772.02011-12?OpenDocument

Waehrer GM, Dong XS, Miller T, Haile E, Men Y. Costs of occupational injuries in construction in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(6):1258–1266.

Amick BC, Hogg-Johnson S, Latour-Villamil D, Saunders R. Protecting construction worker health and safety in Ontario, Canada. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(12):1337–1342.

Dunstan DA, MacEachen E. Bearing the brunt: co-workers’ experiences of work reintegration processes. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(1):44–54.

Iacuone D. “Real men are tough guys”: Hegemonic masculinity and safety in the construction industry. J Mens Stud. 2005;13(2):247–266.

Styhre A. In the circuit of credibility: construction workers and the norms of ‘a good job.’ Constr Manag Econ. 2011;29(2):199–209.

Acknowledgements

We thank University of British Columbia librarian Ursula Ellis for her support during the search phase and Minal Pachchigar (MP) for her contributions during the screening phase of the review.

Funding

Funding was provided from the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board of Ontario, Canada (Grant No. MCLE2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM and KS contributed to the design and implementation of the research. FSH and KS contributed substantially to the analysis of the data. KS and TA drafted the manuscript. CM and FSH provided critical review. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharpe, K., Afshar, T., St-Hilaire, F. et al. Return-to-Work After Work-Related Injury in the Construction Sector: A Scoping Review. J Occup Rehabil 32, 664–684 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10028-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10028-9