Festa and Music at the Court of Marie Casimire Sobieska in Rome (1699–1714)

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- I Festa

- The Festa as a Political Commentary

- The Festa as an Expression of the Power of Christianity and of the Leading Role of Rome

- The Festa as a Mark of Social Prestige

- The Festa as an Expression of a Personal Passion

- The Carnival

- II The Life of Marie Casimire

- Marie Casimire as the Queen of Poland

- A Precièuse in Poland

- The Journey to Rome

- Marie Casimire in Rome

- III Rome at the Turn of Seventeenth and Eigtheenth Centuries

- The Political Context

- The Social Context

- The Intellectual Life

- Accademia dell’Arcadia

- New Trends in Literature and Theatre

- Arcadians’ Views on Music

- Reforming the Operatic Libretti

- Serenatas, Cantatas and Oratorios

- IV Marie Casimire Sobieska’s Capabilities for Financing Art

- V Marie Casimire’s Use of Musical Space in Her Roman Spectacles

- The Theatre

- Open-Air Events

- Churches as Venues

- VI The Audience of the Feste Held by Marie Casimire in Rome

- VII Artists

- Poets

- Carlo Sigismondo Capece

- Giacomo Buonaccorsi

- Giovanni Domenico Pioli

- Monsieur di Prugien (?)

- Filippo Juvarra (as Stage Designer)

- Composers

- Alessandro Scarlatti

- Domenico Scarlatti

- Silvius Leopold Weiss

- Quirino Colombani

- Anastasio Lingua

- Pietro Franchi

- Paolo Lorenzani and Arcangelo Corelli

- Other Musicians

- Singers

- Anna Maria Giusti, Otherwise Known as La Romanina

- Paola Alari

- Caterina Lelli, Otherwise Known as Nina

- Maria Domenica Pini, Otherwise Known as Tilla

- Giovanna Albertini, Otherwise Known as la Reggiana

- Diamante Maria Scarabelli, Otherwise Known as Diamantina

- Lucinda Diana Grifoni

- Victoria, Otherwise Known as Tola di Bocca di Leone

- Faustina

- Livia Dorotea Nanini-Costantini

- Giuseppe della Regina, that is, Giuseppe Luparini-Beccari (?)

- Pippo della Grance

- Giulietta

- Sonnets as a Tribute to Marie Casimire’s Singers

- VIII The Music Genres Practised in the Circle of Marie Casimire Sobieska’s Arts Patronage

- The Libretti of Operas Staged at Marie Casimire’s Theatre

- Il figlio delle selve (17th January 1709)

- La Silvia (26th January 1710)

- Tolomeo et Alessandro ovvero la corona disprezzata (19th January 1711)

- L’Orlando overo La Gelosa Pazzia (1711)

- Tetide in Sciro (10th January 1712)

- Ifigenia in Aulide (11th January 1713) and Ifigenia in Tauri (15th February 1713)

- Amor d’un Ombra, e Gelosia d’un Aura (20th January 1714)

- Carlo Sigismondo Capece’s drammi per musica

- The Dominance of the Pastoral Mode

- Literary Inspirations in Capece’s Libretti

- The Protagonists

- The Structure of the Libretti

- Liaison des scenes

- The Music

- Source Information

- The Structure of Libretti and the Music Composer’s Approach to the Text

- The Musical Characterisation of Dramatis Personae

- The Overtures

- The Arias

- Aria Structures

- Instrumentation

- Vocal Virtuosity

- The Affects

- Ensemble Scenes

- The Recitatives

- The Serenate

- Meaning of the Term and History of the Genre

- Il Tebro fatidico and Introduttione al ballo dell’Aurora (1704)

- Applausi del Sole e della Senna (1704)

- L’Amicizia d’Hercole, e Theseo

- La vittoria della Fede (1708) and Applauso Devoto al Nome di Maria Santissima (1712)

- La vittoria della Fede

- Applauso Devoto al Nome di Maria Santissima

- La gloria innamorata (1709)

- Clori, e Fileno (1712)

- Balli

- Sacred Music

- The Oratorio

- La conversione di Clodoveo, re di Francia (1709)

- Conclusions

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Introduction

When Marie Casimire reached Rome on 23rd March 1699, thus opening an entirely new chapter in her life, she was fifty-eight – quite old by the standards of that age, also taking into account about a dozen births and the burden of hard experiences which fate did not spare her. Nevertheless, as in every life story, she had also had her glorious and happy moments. In the beginning she was Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga’s favourite maidservant. Later she married Jan Zamoyski, one of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s richest persons. Then she was unexpectedly placed on the throne of her adopted homeland when her second, beloved husband, Jan Sobieski, became king. Madelaine de Scudéry comments: “Here we have a wonderful fortune for a maiden who had no fortune of her own. It is indeed an honour for the French nobility.”1 The couple’s years of reign satisfied beautiful Marie’s ambitions, among others thanks to John III’s military successes and the Sobieskis’ rising status in international politics. Still, this period also proved extremely difficult. The deteriorating economic situation and the ineffective system of managing the country both led to eternal conflicts with her subjects and made the Queen engage in courtly intrigues. Combined with Marie Casimire’s changeable moods and unsteady character, all this did little to win her favour with the Poles or the trust of foreign envoys residing in the Commonwealth. The death of John III in 1696, which caused the Polish Queen to throw herself into the hurly-burly of politics in order to retain the crown for the Sobieski family, exposed the negative aspects of her personality and her downright scandalous relations with her eldest son Jakub. Having squandered all the Sobieskis’ chances to remain in power in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and having brought disgrace on the family name, she chose to leave Poland as the best option still available. Rome seemed ideal as the new place of residence. The Pope venerated the memory of the ‘scourge of the infidels,’ the Queen Dowager’s famous husband, which gave her hopes that her stay in Rome would be calm, but worthy of her status. The Jubilee Year was coming soon and could be used as a convenient official excuse for her retreat. Unexpectedly to herself, but also to the Roman authorities, Marie Casimire’s residence in Rome would last for nearly 15 years.

←11 | 12→The Queen soon adjusted to the local environment. The strength of her husband’s name, as well as her own royal past, opened for her the doors of palaces belonging to the Eternal City’s most important personages. The Queen thus visited the residences of Roman and foreign aristocrats, diplomats, the cardinals (who were all-powerful in Rome), and of noble ladies. She herself held meetings and receptions at her apartments in Piazza dei Santi Apostoli, which Livio Odescalchi, Duke of Bracciano, Ceri and Sirmium, kindly offered to her at the beginning of her stay. She dedicated herself to acts of piety with a nearly Counter-Reformation-style zeal, frequenting Rome’s numerous churches. She also derived much joy, however, from purely secular pleasures. Perfectly aware of the impact of art as employed in the service of politics, she took great care to meticulously prepare the theatrical spectacles and occasional pieces staged at the Palazzo Zuccari, which became her permanent residence in 1702. The main purport of those compositions was the recollection and praise of her husband and of the Sobieski family. Though her possibilities in the world of Roman and European politics, dominated by male power, were small, her determination, the desire to make her presence felt in public life, along with her love of splendour and need for admiration, all made a strong mark on Rome’s life.

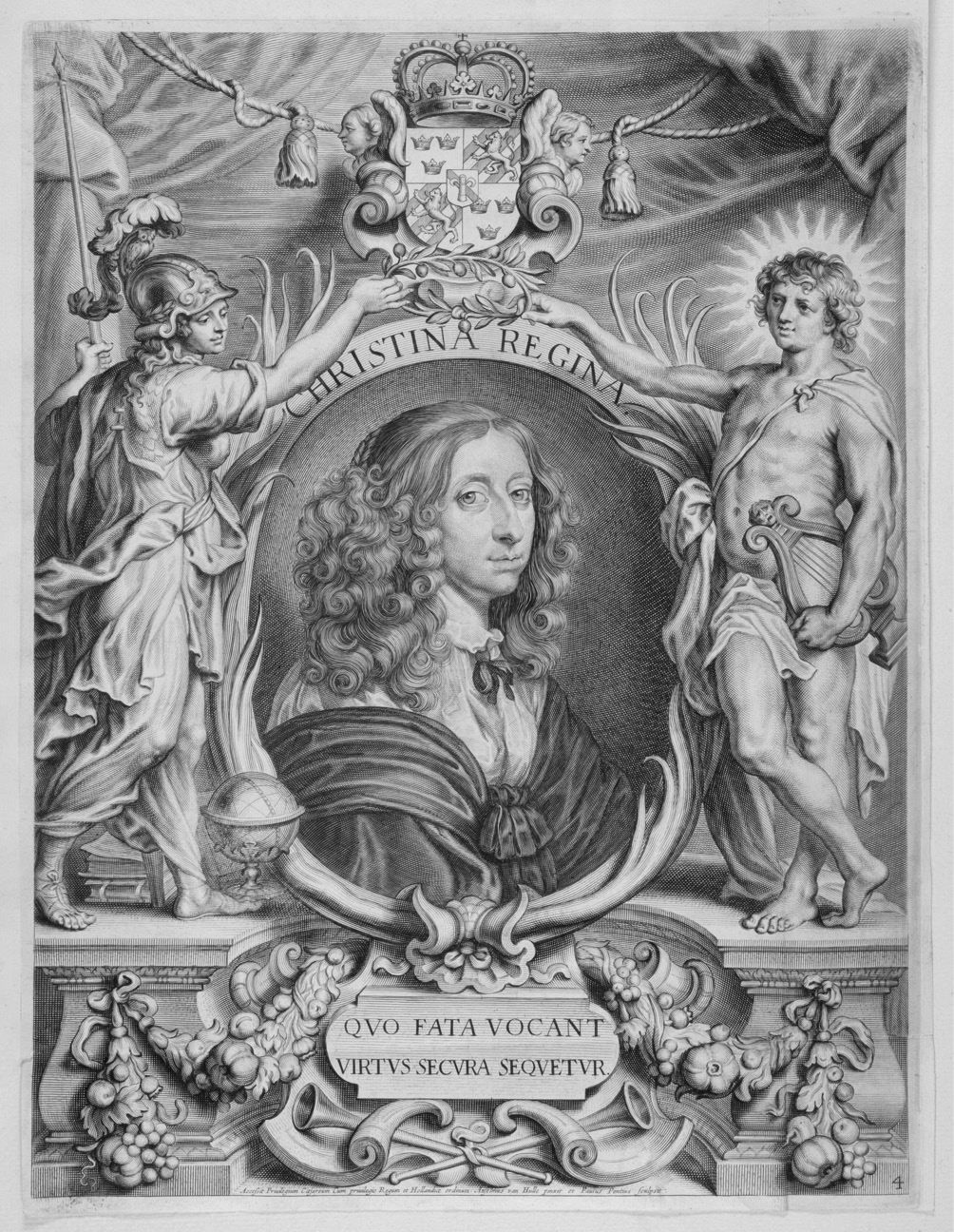

Attracting the attention of the Roman society was, it must be remembered, by no means easy. Marie Casimire had major rivals to compete with in the field of music and theatre patronage. The most important of them, who, however, was always ready to offer his advice, was Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. Another equally important competitor in her quest for fame was Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli, one of Rome’s richest citizens at that time and the main patron of both George Frideric Handel and Antonio Caldara. Apart from these two, there were also more or less sumptuous courts run by the ambassadors of various countries, as well as the Teatro Capranica, which was Rome’s only public opera house in operation during the Polish Queen’s stay in Rome. No less influential than the above-mentioned aristocrats, though no longer alive, was Sobieska’s predecessor in the Eternal City, the Swedish Queen Christina, to whom Marie Casimire has been compared both during her Roman period and in later texts dedicated to this subject.

It seems worthwhile to dedicate some space to that latter figure, whose fame cast a long shadow on the assessments of Marie Casimire’s own achievements in Rome. Having converted from Protestantism to Catholicism in 1654, Christina abdicated and set out for Rome, where her conversion “was planned to be a massive propaganda victory for the Vatican.”2 It soon turned out, however, that the ←12 | 13→Swedish queen did not yield easily to the pope’s dictates. When the plot which she hatched with Cardinal Giulio Mazzarini3 was uncovered, Christina lost her image of a pious convert,4 especially since the Neapolitan marquis Gian Rinaldo Monaldescho, who had divulged the plan of attack on Naples to the pope and the Spaniards, was murdered on her orders. For obvious reasons, the pope tried to find a place for Christina outside of Rome, which led to various concepts, including her candidature for the throne of Poland in 1668. When all these initiatives failed, she settled permanently in Rome, where she gained recognition and respect as a patroness of the arts and of a group of intellectuals who belonged to her circle. She no longer had any actual influence in the European political scene, and this – together with her well-thought-out artistic patronage – makes her story similar to that of Marie Casimire. In Rome, however, the Polish queen was held in much less reverence than her Swedish predecessor, as evident, for instance, from one of the most frequently quoted versified lampoons, noted down by Rome’s chronicler Francesco Valesio in the early period of Sobieska’s stay in the Eternal City:

A simple hen born of a rooster

lived among the chickens and became a queen;

she came to Rome, a Christian, but not a Christina.5

This anonymous three-line poem is a spiteful summary of Marie Casimire’s life story. To begin with, the author reminds his readers that she was not of royal blood, thus refusing to accord her the same status that was enjoyed by Queen Christina. Secondly, he suggests in a few words that – though Marie Casimire’s piety bordered on the sanctimonious – she lacked the Swede’s mental powers and personality. Christina indisputably outclassed the Polish Queen in terms of intellect, scope of interests, and most of all – education. She knew several modern languages as well as Latin and Greek; she studied philosophy, theology, history, and art; she corresponded with the great minds of the age.6 As a member of the royal family, unlike the protagonist of this book, Christina had been trained for ←13 | 14→the role of a monarch from her earliest years. Her vivid and versatile mind made this task all the easier for her. On the other hand, though, the Swedish Queen’s musical patronage, though involving such representative Baroque masters as Giacomo Carissimi, Alessandro Stradella, the young Alessandro Scarlatti, and Arcangelo Corelli, is not well documented in sources and leaves much space for conjecture.7 In most cases, not only the scores but even the libretti of the drammi per musica sponsored by Christina have not been preserved. Most likely many of the operas associated with her patronage were not staged in the palace where she resided, since none of its chambers fulfilled the basic requirements for a theatrical stage. Despite this drawback, Christina’s contributions to Roman culture in the second half of the seventeenth century were enormous. Her greatest achievements include initiating such events as the opening of the first public operatic theatre (Il Tordinona), a cycle of Easter oratorios staged in secular settings, as well as the organisation of various academies dedicated to science, philosophy, and art, of which music was a regular component.8 She managed to carry out all these projects despite the ever-diminishing funds which she received from the successive popes.

Christina’s merits can hardly be overestimated, and it is not the present author’s aim to deny them. It seems, however, that Marie Casimire’s patronage should not be assessed exclusively in the context of the achievements of the Swedish Queen. Despite their bothersome personalities and somewhat similar, difficult life histories, both monarchs created interesting artistic venues in Rome and initiated works of art which bear witness to their good tastes and continue to delight us with their beauty. These works reflect their aspirations, experiences, and (we should remember) also their financial potential. Poor gentlewomen encountered many limitations in the early modern societies. Marie Casimire overcame them all; her heritage bears witness to the strength of her character and her higher-than-average intelligence. Her attitude should therefore command respect since it confirms the words of one of John III’s most recent biographers, Zbigniew Wójcik, who claims that despite numerous faults she “should be considered as one of the most intelligent and outstanding women who shared the Polish throne with their royal husbands in the modern era.”9 Her Roman patronage of the arts ←14 | 15→proves that she proudly continued to represent her adopted homeland also after leaving the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

***

Marie Casimire Sobieska’s musical patronage in Rome has never been the subject of a comprehensive research monograph; the present study is the first attempt at such a publication. This does not mean, however, that the Polish Queen has not attracted the interest of researchers. On the contrary, she has sparked many emotions and debates among historians who have analysed John III’s achievements and failures. The Sobieski marriage was an intriguing and attractive ←15 | 16→topic, especially in the realities of Poland under the Partitions. In its steadfast efforts to retain its national identity, the Polish society needed the great heroes of the past. This made Polish historians focus on the champion of the Battle of Vienna with special ardour, while his political mistakes and military defeats were blamed on Marie Casimire. John III was thus idealised at the expense of his wife. One of the nineteenth century writers, Jan Turski, even found her responsible for the Partitions of Poland, when he thus emphatically stated: “Our later ordeals, the cross that we have to bear and death, till the moment when God bids his angels to remove the stone from the entrance to our tomb – it was she who brought all this upon Poland.”10

Historians’ opinions concerning Marie Casimire began to change after World War I. As Michał Komaszyński explains, “The debate concerning the queen’s political impact has lost its political significance, and only continues to attract the interest of a narrow academic circle. True to the spirit of the time, the Aurora has turned into an embodiment of feminine sensuality.”11 What has also contributed to this process was the reception of Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński’s popular novel entitled Marysieńka Sobieska12 (‘Marysieńka,’ a diminutive of Maria, which is how John III addressed his wife). It should be stressed, however, that as a ‘sexual creature’ Marie Casimire has intrigued authors from the very start, which is confirmed by the numerous descriptions of her extraordinary beauty. More balanced opinions about the Queen began to appear in Polish historiography relatively recently, mostly owing to the writings of the already quoted Professor Komaszyński. In the last decade, our knowledge about Marie and her sons has been significantly extended thanks to Aleksandra Skrzypietz and her analyses of hitherto unknown sources.13 Abroad, a brief chapter has been dedicated to the works written at the Polish Queen’s inspiration by Gaetano Platania,14 who has thus underlined her presence in, and contributions to, the musical life of Rome. In musicology, the figure of Marie Casimire is mentioned mainly on the margin of studies dedicated ←16 | 17→to the life and work of the leading artists whom she employed: Carlo Sigismondo Capece,15 both Scarlattis,16 Silvius Leopold Weiss,17 and Filippo Juvarra;18 as well ←17 | 18→as descriptions of the history of private stages in Rome,19 the Roman carnival traditions,20 and the reception of works premiered at the Polish Queen’s Roman residence.21 Marie Casimire is also referred to in the context of her daughter Teresa Kunegunda Sobieska’s years spent in exile in Venice.22 Those mentions are mostly very short, and if any of these authors (mostly biographers of Domenico Scarlatti) dedicates a longer passage to the Polish Queen, her contributions are assessed through the prism of opinions presented by Kazimierz Waliszewski in his long-since outdated French-language publication, which for many years was the only one available to foreign scholars.23

Polish researchers have dedicated a little more attention to Marie Casimire’s Roman patronage, mainly thanks to the works of Wanda Roszkowska,24 who, ←18 | 19→however, rarely quotes her sources, and frequently reiterates the conviction that the Polish Queen’s stage projects in Rome depended on the ideological and artistic activity of Prince Aleksander Sobieski, while Marie’s role was supposedly limited to providing her son with funds necessary to carry out his plans and his ever growing ambitions as actual patron of the artists. Considering the constant financial straits to which she was reduced, the Queen could easily oppose her son’s ambitions, but she did not. What is more, her letters (preserved at the National Historical Archives of Belarus in Minsk) prove that she supported her son’s theatrical preoccupations as she was aware that they helped him cope with his progressing illness.25 Sobieska’s patronage therefore seems to represent a very interesting aspect of the Baroque opera, namely, the therapeutic one, which is poorly represented in hitherto research despite the many works dedicated to the theory of affections and to music’s influence on the audience.

The main aim of this publication is to discuss and interpret the works commissioned in Rome by Marie Casimire Sobieska, in the context of the feste which she held in Rome, as well as to portray those few composers, librettists and performers whose names have come down to us. Eight libretti of drammi per musica sponsored by the Polish Queen have been preserved to our times, as well as those of six serenate, one oratorio, two complete operatic scores (Tolomeo et Alessandro, Tetide in Sciro), one rifacimento of the last opera staged at the Polish Queen’s Roman theatre (Amor d’un’Ombra e Gelosia d’un’Aura), some individual operatic arias, and a fragment of the score of one serenata (Clori, e Fileno). “Owing to the shortage of funds, the Sobieskis usually fell behind with the rent for their Roman residence, and the food on their table was rather less sumptuous for this reason, but their theatre maintained a high standard,”26 writes Aleksandra Skrzypietz, thus demonstrating that the theatre was one of Marie Casimire’s key priorities.

For lack of sufficient information, I do not deal in my book with instrumental music which was most likely also performed at the Queen’s palace. I will only suggest at this point that the repertoire presented at the Palazzo Zuccari ←19 | 20→probably included solo and trio sonatas, da camera as well as da chiesa (which were often played in secular venues), written by fashionable and highly regarded composers, both from Rome and from other centres. Teresa Kunegunda may have sent her mother the most recent scores by Venetian artists, including Opus 1 by Vivaldi, whom the Electress valued very highly. It is also highly probable that Domenico Scarlatti improvised his early harpsichord sonatas at the Queen’s palace, in the style of those pieces which now bear the catalogue numbers K. 82 and K. 85. He may also have played for her some French suites, though in his own output one can hardly trace the influence of the French harpsichord masters. What we can be quite certain of is that on lonely evenings the Queen did listen to suites, sonatas and variations played by Silvius Leopold Weiss, as confirmed by the so-called Poliński lute tablature surviving in Paris and believed to have been compiled in Venice.27 Apart from the earliest known pieces by S.L. Weiss and his brother, this tablature also comprises works by the French lutenists Jacques Gallot and Charles Mouton, as well as the Czech composer Jan Antonín Losy, all of which Weiss may well have performed for the Queen. Furthermore, we find there compositions by Corelli and, most significantly for our subject, the final chorus Lieto Giorno from the opera Tolomeo et Alessandro, entered in Weiss’s own hand.28 This raises questions about the links between this tablature and the Polish Queen’s Roman court.

Marie Casimire must also have been familiar with the sonatas of Arcangelo Corelli, which she may have heard performed with Domenico Scarlatti and Silvius L. Weiss interpreting the continuo. But who were the soloists? This cannot be said with any certainty. Apart from the above-mentioned composers, musicians active at Sobieska’s court also included those whom she had brought to Rome from Poland. At larger receptions and especially at the balli the Queen’s guests were ←20 | 21→probably accompanied by a small string orchestra, which performed alternating Italian, French, and possibly also Polish dances. Unfortunately, for lack of preserved courtly bills or other sources from the period, instrumental music at the Queen’s palace and its potential performers are still a matter of conjecture.

The book Festa i muzyka na dworze Marii Kazimiery Sobieskiej w Rzymie (1699–1714) [Feste and Music at the Court of Marie Casimire Sobieska in Rome, 1699–1714] was first published in Polish in 2012 by the Museum of King John III’s Palace at Wilanów as a follow-up from my PhD dissertation written under the supervision of Professor Alina Żórawska-Witkowska at Warsaw University. It has taken several years for the English-language version to come out. In this new version, I have used my best efforts to include all the most recent findings concerning Queen Marie Casimire that have appeared in the meantime in the literature of the subject. Most importantly, however, I have supplemented the English edition with quotations and information from previously unknown letters written by the Queen to her son Jakub Sobieski, and now kept at the National Historical Archives of Belarus in Minsk.

At this point, I would also like to express my gratitude to Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska and Sławomira Żerańska-Kominek for their precious comments, as well as to Pierluigi Petrobelli, Giovanni Morelli, Fabio Biondi, Jerzy Żak, Berthold Over, Teresa Chirico, Reinhard Strohm, Bruno Forment, Alberto Basso, Norbert Dubovy, and Dinko Fabris, who have helped me gain access to important scores, and exchanged with me their views and expert opinions on the subject.

I also owe my most sincere thanks to Mr Paweł Jaskanis, director of the Museum of King John III’s Palace at Wilanów, for the permission to print materials in the Polish-language version of the book, and for his consent to include illustrations in its present, English edition. My thanks also go to Ms Elżbieta Grygiel, curator of the ‘Silva Rerum’ programme, for her trust in my project; to the publisher, Peter Lang, for printing the book in English; and, last but not least, to the translators.

1Qtd. after K. Targosz, Sawantki w Polsce w XVII w. Aspiracje intelektualne kobiet ze środowisk dworskich [Educated Women in 17th-c. Poland. The Intellectual Aspirations of Women from the Courtly Circles] (Warszawa: Retro-Art, 1997), p. 216.

2S. Åkerman, Queen Christina of Sweden and Her Circle. The Transformation of a Seventeenth-Century Philosophical Libertine (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1991), p. 225.

3They planned to launch a military attack on Naples, which was a Spanish territory at that time; it was to become Christina’s new kingdom following her victory.

4S. Åkerman, Queen Christina…, p. 233.

5“Nacqui da un gallo semplice gallina / vissi tra li pollastri e fui reggina / venni a Roma cristiana e non Cristina,” in: F. Valesio, Diario di Roma, ed. G. Scano, Vol. 1 (Milano: Longanesi, 1977–1979), p. 32.

6V. Buckley, Cristina regina di Svezia. La vita tempestosa di un’europea eccentrica (Milano: Mondadori, 2006).

7A. Morelli, “Il mecenatismo musicale di Cristina di Svezia. Una riconsiderazione,” in: Cristina di Svezia e la musica. Atti di convegno dei Lincei, [no editor] (Roma: Accademia Naz. dei Lincei, 1998), pp. 321–346.

8A. Morelli, “Il mecenatismo…,” p. 331.

9Z. Wójcik, Jan Sobieski 1629–1696 (Warszawa: PIW, 1983), p. 403.

10M. Komaszyński,Królowa Maria Kazimiera [Queen Marie Casimire] (Warszawa: Arx Regia, 1992), pp. 93–94.

11M. Komaszyński,Królowa Maria Kazimiera, p. 93.

12T. Boy-Żeleński, Marysieńka Sobieska (Lwów-Warszawa: Książnica Atlas, 1937).

13A. Skrzypietz, Królewscy synowie – Jakub, Aleksander i Konstanty Sobiescy [The Royal Sons: Jakub, Aleksander and Konstanty Sobieski] (Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2011).

14G. Platania, Gli ultimi Sobieski e Roma. Fasti e miserie di una famiglia reale polacca tra sei e settecento (1699–1715), Roma: Vecchiarelli editore, 1990.

15A. Cametti, “Carlo Sigismondo Capeci (1652–1728). Alessandro e Domenico Scarlatti e la Regina di Polonia in Roma,” Musica d’oggi 1931, No. 2, pp. 55–64; M. Di Martino, “Oblio e recupero di un librettista settecentesco: Carlo Sigismondo Capeci (1652–1728) e il melodrama arcadico,” Nuova Rivista Musicale Italiana 1996, Nos. 1–2, pp. 31–55.

16Of the many publications that have been dedicated to Alessandro and Domenico Scarlattis, let me list the major ones from among those which mention the figure of Marie Casimire. These are: R. Kirkpatrick, Domenico Scarlatti (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953); M. Boyd, Domenico Scarlatti, Master of Music (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986); M. Boyd, “‘The Music Very Good Indeed’: Scarlatti’s Tolomeo et Alessandro Recovered,” in: Studies in Music History Presented to H. C. Robbins Landon on his Seventieth Birthday, eds O. Biba and D.W. Jones (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996); A. della Corte, “‘Tetide in Sciro’ l’opera di Domenico Scarlatti ritrovata,” La Rassegna Musicale 1957, No. 4; S.A. Lucciani, “Un’opera inedita di Domenico Scarlatti,” Rivista Musicale Italiana 1946, No. 4; A.D. McCredie, “Domenico Scarlatti and his Opera ‘Narcisso,’” Acta Musicologica 1961, No. 1; R. Pagano, Scarlatti Alessandro e Domenico: due vite in una (Milano: A. Mondadori, 1985), English edition: Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti. Two Lives in One, trans. F. Hammond (Hillsdale: Pendragon, 2006); D. Fabris, “Le gare d’amore e di politica. Domenico Scarlatti al servizio di Maria Casimira,” in: I Sobieski a Roma. La famiglia reale polacca nella Città Eterna, eds Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Zuzanna Flisowska, Paweł Migasiewicz (Warszawa: Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2018), pp. 220–248.

Details

- Pages

- 424

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631844274

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631846438

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631846445

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631842577

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17872

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Keywords

- baroque opera Domenico Scarlatti music and politics Sobieski family music patronage women’s patronage

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 424 pp., 29 fig. b/w, 9 tables.