Abstract

Background

Cognitive functioning has been linked to employment outcomes in multiple sclerosis (MS) in cross-sectional studies. Longitudinal studies are however lacking and previous studies did not extensively examine executive functioning.

Objectives

We examined whether baseline cognitive functioning predicts a change in employment status after 2 years, while taking into account mood, fatigue and disability level.

Methods

A total of 124 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (pwMS) and 60 healthy controls were included. They underwent neurological and neuropsychological examinations and completed online questionnaires. PwMS were divided into a stable and deteriorated employment status group (SES and DES), based on employment status 2 years after baseline. We first examined baseline differences between the SES and DES groups in cognitive functioning, mood, fatigue and disability level. A logistic regression analysis was performed, with change in employment status (SES/DES) as dependent variable.

Results

The DES group included 22% pwMS. Group differences were found in complex attention, executive functioning, self-reported cognitive functioning, fatigue and physical disability. More physical disability (OR = 1.90, p = 0.01) and lower executive functioning (OR = 0.30, p = 0.03) were retained as independent predictors of DES (R2 = 0.22, p ≤ 0.001).

Conclusions

Baseline physical disability and executive functioning, but none of the other variables, moderately predicted a deterioration in employment status 2 years later.

Trial registration

This observational study is registered under NL43098.008.12: ‘Voorspellers van arbeidsparticipatie bij mensen met relapsing-remitting Multiple Sclerose’. This study is registered at the Dutch CCMO register (https://www.toetsingonline.nl).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

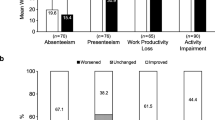

Work participation plays an important role in our lives and is often linked to quality of life. Besides income, work participation is known to promote a person’s sense of self-respect and social contacts and provides a feeling of usefulness and satisfaction [1]. Living with a chronic illness can make it challenging to meet the demands of working life. As a result, work participation is often compromised in patients with multiple sclerosis (pwMS) with unemployment rates up to 80% [2]. In those who remain in the workforce, a reduction in hours or work responsibilities, presenteeism and increased time missed from work is often observed [3].

Whether and how pwMS participate in work depends on multiple factors [4, 5]. Physical disability, disease duration, the patient’s age, fatigue, walking problems, cognitive and neuropsychological impairments are linked to difficulties with work participation [4, 6]. Cognitive impairment is present in an estimated 43 to 65% of pwMS and can be present at all stages of the disease [7]. In accordance with the fickle nature of the disease, a wide variety of cognitive deficits can be observed in MS with a great inter-patient variability. In addition, cognitive resources have become more important as the work field over the past decades has changed from an industrial to a post-industrial setting, resulting into a shift from more physically challenging work toward more mentally challenging work [8]. Studies have suggested that cognitive functioning, either self-reported or objectively assessed with a cognitive examination, plays an important role in work participation. Specifically, self-reported cognitive difficulties, global cognitive impairment and lower scores on processing speed/working memory, executive functioning and memory have been linked to worse work outcomes in MS [9,10,11]. The majority of studies on cognitive functioning and work outcomes are, however, cross-sectional, which makes it impossible to draw conclusions about causality of relationships, and on the predictive value of cognitive functioning regarding work participation in MS. The few longitudinal studies that were conducted found evidence for the predictive value of processing speed/working memory for future employment status [12,13,14]. Many of the previous studies, including the longitudinal ones, did not examine executive functioning in much detail, while measures of conceptual reasoning, switching and inhibition may be important associates of work functioning [13, 15].

In the current study, we aim to investigate whether baseline cognitive functioning predicts a change in employment status after 2 years, while taking mood, fatigue and disability level into account.

Materials and methods

Design and procedure

For this study, pwMS from 16 MS outpatient clinics in the Netherlands were recruited in the context of the MS@Work study, a prospective longitudinal study on work participation in patients with relapsing-remitting MS [5]. The criteria for inclusion were a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS [16], patients had to be 18 years and older and currently employed or within 3 years since their last employment. Patients with comorbid psychiatric or neurological disorders, substance abuse, neurological impairment that might interfere with cognitive testing, or inability to speak and/or read Dutch were excluded from the study. A healthy control group was recruited through advertisements on social media and in local newspapers. For the healthy control group, the same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used, except for absence of a chronic disorder.

PwMS underwent neurological and neuropsychological examinations at their outpatient clinics and were asked to fill in online questionnaires yearly for a period of 3 years. The healthy controls underwent a neuropsychological examination at baseline and were asked to fill in the online questionnaires yearly for a period of 3 years. For this study, the baseline and 2-year data were used. The online questionnaires assessed demographic characteristics, work participation, empathy, self-reported cognitive and neuropsychiatric functioning, fatigue and mood.

The MS@Work study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee Brabant (NL43098.008.12 1307; date of approval: 12-02-2014) and the Board of Directors of the participating MS outpatient clinics. All subjects provided written informed consent. The study was performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki [17].

Participants

The current study included pwMS who were employed at baseline, completed the baseline assessments and completed questionnaires about their work situation after 2 years (see Fig. 1 for a flow chart of the inclusion of participants). Participants were categorised into a stable employment status (SES) group (n = 97) and a deteriorated employment status (DES) group (n = 27), based on deteriorations in their work status after 2 years (see measures for a definition). We included 60 healthy controls, matched for age, sex and education to be able to calculate Z-scores for cognitive functioning, anxiety, depression and fatigue.

Measures

Neuropsychological examination

The neuropsychological examination included various neuropsychological tests assessing the neurocognitive domains as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V [18] (i.e. complex attention, learning and memory, language, executive functioning, perceptual motor functioning and social cognition). For an overview of the neuropsychological tests and measures, see Table 1. Most tests are part of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in MS battery [19]. The Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire [20] was used to examine self-reported cognitive and neuropsychiatric functioning. Neuropsychological test scores were transformed into Z-scores based on the healthy control group and composite Z-scores were calculated per neurocognitive domain.

Employment status

A general questionnaire was used to inquire about demographic characteristics and work participation in both the patients and healthy controls. The general questionnaire was administered at baseline and 2 years after baseline. Participants were regarded to be employed if they were in a paid job or reported to be self-employed. Students, volunteer workers and participants who had reached the retirement age were excluded from analysis.

Participants were divided into SES and DES groups based on deteriorations reported in the 2-year data. A participant was considered to be part of the DES group if they either had stopped working due to MS or had decreased their work hours due to MS by at least 20% based on self-reports. Participants, who reported no differences or had increased their work hours, were included in the SES group.

Other clinical measures

The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was used to examine physical disability in pwMS [21] and was administered by a neurologist in the outpatient clinic where the patients were being treated. Scores range from 0 (normal neurological exam) to 10 (death due to MS) and increment with steps of 0.5. Scores between 0 and 3.5 represent mild disability, scores between 4.0 and 6.5 represent moderate disability and scores of 7.0 and above represent severe disability [22]. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [23] was used to examine self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. The Modified Fatigue Impact Scale was used to measure the self-reported impact of fatigue on daily functioning [24].

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS for Windows (release 23.0) was used for data analysis. Z-scores were calculated for the neurocognitive measures, self-reported cognitive functioning, depression, anxiety and fatigue based on the mean and standard deviation (SD) from the healthy control group. Z-scores were scaled in such a way that lower scores represent worse functioning and combined into a mean Z-score for each neurocognitive domain.

In the first step of analysis, we investigated differences between the SES and DES groups in Z-scores per neurocognitive domain and other clinical measures using parametric or non-parametric tests where appropriate.

In the second step of analysis, we conducted a logistic regression analysis, with change in employment status (SES/DES) as dependent variable. As potential predictors, we included the Z-scores per neurocognitive domain and the other clinical measures that significantly differed between the DES and SES group as shown in the previous step of the analysis. The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients with MS

Demographics and disease characteristics of the pwMS and healthy controls are presented in Table 2. Patients and healthy controls did not differ significantly in gender, age, educational level and type of job. The pwMS worked significantly less hours than the healthy controls (U = 2246.0, p < 0.001). Most pwMS had a white collar job (88.2%), with the majority being employed in office and administrative support (20.5%), the healthcare sector (16.5%) or education sector (11.8%). The pwMS were characterised by mild disability (median 2.0).

In Table 3, the mean Z-scores for the neurocognitive domains, self-reported cognitive functioning, anxiety, depression and fatigue are presented. The neurocognitive domains where patients most frequently scored below average (≤ 2SD as compared with healthy controls) are complex attention (8.9%), followed by perceptual motor functioning (5.7%) and learning and memory (3.2%). A total of 20 pwMS (16.1%) scored below average (≤ 2SD) on at least one neurocognitive domain. A total of 8.9% and 10.5% of the pwMS reported scores indicative of major depression and generalised anxiety, and 26.6% reported scores indicative of MS-related fatigue (based on ≤ 2SD).

Baseline comparisons between the SES and DES groups

Baseline comparisons between the SES and DES groups in demographic characteristics, cognitive functioning and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 4. In 27 cases, patient’s employment deteriorated (DES; 22%). Of the 97 that were in the SES group (78%), four patients reported an increase in work hours. The SES and DES groups did not differ in gender, age, educational level, work hours, type of work, the use of immunomodulatory treatment, disease duration, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor functioning, social cognition and anxiety at baseline. The DES group showed more physical disability, lower complex attention and executive functioning, more self-reported cognitive problems, more symptoms of depression, and more fatigue than the SES group at baseline.

Predictors of changes in employment status after 2 years

Results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 5. Lower executive functioning and more physical disability were retained as independent predictors of DES. All other variables did not independently contribute to the prediction.

Discussion

This longitudinal study shows that pwMS who deteriorated in employment status after 2 years due to MS showed lower executive functioning, more self-reported cognitive problems, more symptoms of depression, higher fatigue and higher physical disability (i.e. higher EDSS scores) at baseline. These findings are in accordance with factors that have previously been linked to worse employment outcomes in cross-sectional studies [6]. Our logistic regression model retained more physical disability and lower executive functioning as independent baseline predictors of a deterioration in employment status over a 2-year period. All other variables did not significantly predict DES 2 years after baseline. Both physical disability and executive functioning have previously been linked with work participation in multiple (mostly) cross-sectional studies [6, 9]. Although the level of physical disability in our group of pwMS can be considered mild, it seems that more physical disability is an important risk factor for less favourable employment outcomes over time.

None of the pwMS in this study showed below average (< 2SD) executive functioning at baseline. Still, lower executive functioning was found to be predictive of DES. This is not surprising, because executive functioning is thought to be crucial for successful work participation, as most job demands include executive abilities such as problem solving, planning and reasoning [25].

Comparing our results with the few other longitudinal studies, Morrow et al. (2010) found that both baseline and a decline in processing speed/working memory (Symbol Digit Modalities Test) and verbal memory predicted a deterioration in vocational status 3 years later [12]. Ruet et al. (2013) found that lower baseline processing speed/working memory (Symbol Digit Modalities Test and Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test), more physical disability and higher age were significantly associated with a decreased employment status after 7 years [13]. In the register-based cohort study by Kavaliunas et al. (2019), a relation between baseline lower processing speed (Symbol Digit Modalities Test) and work disability (sickness absence and disability pensioned) at 1 and 3 years after follow-up was found [14].

All these longitudinal studies found evidence for the influence of processing speed/working memory on future employment status, but did not comprehensively evaluate executive functioning.

In our study, the neurocognitive domain of executive functioning reflects the combined performance on the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test and complex conditions of the Trail Making Test, Colour Word Interference Test and Design Fluency. Upon further inspection, we found that specifically the scores on the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test and Colour Word Interference Test differed between the SES and DES groups (see online supplementary material). The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test has been previously linked to employment outcomes in pwMS [19, 26] and is regarded as one of the most sensitive measures for employment outcomes, together with the Symbol Digit Modalities Test [11,12,13, 27]. The Colour Word Interference Test measures both inhibition and cognitive flexibility [28] and may also be influenced by a processing speed component. In the little research that has used the Colour Word Interference Test as a measure of executive functioning in combination with employment status, no associations were found [29, 30]. However, the Colour Word Interference Test may provide a measure of inhibition and cognitive flexibility (either combined with processing speed) that is representative of the ability to overcome challenges faced by individuals with MS in the workplace.

Although we observed group differences in self-reported cognitive functioning, fatigue and depression between the SES and DES groups, these variables were not retained as independent predictors of DES after 2 years. Self-reported cognitive functioning as measured with the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire was previously found to be related with employment status [31] and negative work events [32]. Furthermore, previous research shows strong evidence that both fatigue and depression are associated with work outcomes [6]. A possible explanation for the lack of baseline predictive power is that these variables are subject to time-dependent changes. It is known that depression as well as anxiety can change over time in pwMS [33]. In line, it seems intuitive that fatigue scores fluctuate over time influenced by primary and secondary mechanisms (e.g. sleep disorder, depression, iatrogenic mechanisms) [34]. It would be interesting to further investigate change scores of fatigue, depression, anxiety and self-reported cognitive functioning over time in relation to changes in employment outcomes.

Even though physical disability and executive functioning are predictors of DES, together they were only able to explain a small part of the variance in DES. Work participation in MS is a multifactorial problem and cannot solely be explained by the measured variables. It is known that personal- and work-related factors are related to work participation. For example, the willingness of companies to facilitate suitable adaptations like flexible work schedule or accommodations to the workload may be as important [35]. To date, the amount of studies investigating these (and other) personal- and work-related factors is limited and it might be of great interest to investigate these factors more extensively.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include its longitudinal character, the use of a matched control group and the use of a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. The study sample was characterised by working patients with relapsing-remitting MS, mild physical disability and a low prevalence of patients showing below average performance on the six neurocognitive domains (0–8.9%), and thus its findings may probably not be generalisable to the entire MS population. Furthermore, with the use of questionnaires, our self-reported work measure may be subject to a recall bias.

In our outcome measure, we did not include presenteeism or qualitative deteriorations in employment, like loss of responsibilities or other changes of function due to MS. PwMS that worked in a less skilled job for the same number of work hours 2 years after baseline, were not considered to be in the deteriorated group. In this regard, it is possible that pwMS in the stable group did qualitatively deteriorate in employment status and thus, the effects found could possibly be an underestimation of the true effect.

In the current study, we have taken into account various influential factors like mood, fatigue and disability level. Another possible influential factor, that we did not take into account, is the use of immunomodulatory treatment and switches in treatment over time. Most patients in our sample use disease-modifying drugs, and some of these drugs have been reported to affect cognitive [36] and work functioning [37]. In future studies, it might be interesting to also take into account the potential effects of (changes in) disease-modifying drugs on cognitive functioning and work participation over time. In future research, it would be relevant to investigate changes in cognitive functioning in relation to work participation over time. The only two prospective, longitudinal studies that used a cognitive test battery found that changes in employment status after 3 and 7 years were predicted by both baseline cognitive performance and cognitive deterioration during those years [12, 13]. In future research, the relation between work participation and a possible decrease in cognitive functioning and other clinical-, personal- and work-related factors over time should be investigated. As data collection of the MS@Work study is still ongoing, we plan to focus on this issue in the future.

Although we used a matched control group to calculate standardised scores for the neurocognitive measures, it would be interesting to use meaningful and work-specific reference criteria, such as minimal cognitive ability required to successfully perform a certain work task. This is in line with the model of workload (mental and physical task load) and work capacity (ability to execute a task) [38]. Similar work-related reference values have been established for a functional capacity evaluation of physical functioning [39]. However, references are currently unavailable for cognitive functioning in relation to work, which limits meaningful interpretation of neuropsychological functioning in terms of work capacity, and imposes a relevant venue for future research.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that lower executive functioning and more physical disability are moderately predictive of a deterioration in employment status after 2 years due to MS. Mood and fatigue were not retained as independent predictors of a deterioration in employment status. We should keep in mind that work participation in pwMS is a multifactorial problem. Besides disease-related factors, it might be of great interest to investigate personal- and work-related factors more extensively.

References

Gheaus A, Herzog L (2016) The goods of work (other than money!). J Soc Philos 47(1):70–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12140

Julian LJ, Vella L, Vollmer T, Hadjimichael O, Mohr DC (2008) Employment in multiple sclerosis: exiting and re-entering the work force. J Neurol 255(9):1354–1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-008-0910-y

Uitdehaag B, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Dalén J (2017) New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for the Netherlands. Mult Scler J 23(2_suppl):117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517708663

Schiavolin S, Leonardi M, Giovannetti AM, Antozzi C, Brambilla L, Confalonieri P, Mantegazza R, Raggi A (2013) Factors related to difficulties with employment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of 2002-2011 literature. Int J Rehabil Res 36(2):105–111. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32835c79ea

van der Hiele K, van Gorp DA, Heerings MA, van Lieshout I, Jongen PJ, Reneman MF, van der Klink JJ, Vosman F, Middelkoop HA, Visser LH, Group MSWS (2015) The MS@Work study: a 3-year prospective observational study on factors involved with work participation in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 15:134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-015-0375-4

Raggi A, Covelli V, Schiavolin S, Scaratti C, Leonardi M, Willems M (2016) Work-related problems in multiple sclerosis: a literature review on its associates and determinants. Disabil Rehabil 38(10):936–944. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1070295

Amato MP, Portaccio E, Goretti B, Zipoli V, Hakiki B, Giannini M, Pastò L, Razzolini L (2010) Cognitive impairment in early stages of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 31(2):211–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-010-0376-4

van der Klink JJ, Bultmann U, Burdorf A, Schaufeli WB, Zijlstra FR, Abma FI, Brouwer S, van der Wilt GJ (2016) Sustainable employability-definition, conceptualization, and implications: a perspective based on the capability approach. Scand J Work Environ Health 42(1):71–79. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3531

Clemens L, Langdon D (2018) How does cognition relate to employment in multiple sclerosis? A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord 26:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.018

Honan CA, Brown RF, Batchelor J (2015) Perceived cognitive difficulties and cognitive test performance as predictors of employment outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 21(2):156–168. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617715000053

van Gorp DAM, van der Hiele K, Middelkoop HAM, visser LH (2019) The relation between cognitive functioning and work outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Curr Res Neurol Neurosurg 2(1):011–029

Morrow SA, Drake A, Zivadinov R, Munschauer F, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict RH (2010) Predicting loss of employment over three years in multiple sclerosis: clinically meaningful cognitive decline. Clin Neuropsychol 24(7):1131–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2010.511272

Ruet A, Deloire M, Hamel D, Ouallet JC, Petry K, Brochet B (2013) Cognitive impairment, health-related quality of life and vocational status at early stages of multiple sclerosis: a 7-year longitudinal study. J Neurol 260(3):776–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6705-1

Kavaliunas A, Tinghög P, Friberg E, Olsson T, Alexanderson K, Hillert J, Karrenbauer VD (2019) Cognitive function predicts work disability among multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler J 5(1):205521731882213. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217318822134

Parmenter BA, Zivadinov R, Kerenyi L, Gavett R, Weinstock-Guttman B, Dwyer MG, Garg N, Munschauer F, Benedict RH (2007) Validity of the Wisconsin Card Sorting and Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) sorting tests in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 29(2):215–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803390600672163

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, Fujihara K, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Montalban X, O'Connor P, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Waubant E, Weinshenker B, Wolinsky JS (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 69(2):292–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22366

World Medical Association (2013) Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 310(20):2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Sachdev PS, Blacker D, Blazer DG, Ganguli M, Jeste DV, Paulsen JS, Petersen RC (2014) Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat Rev Neurol 10(11):634–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.181

Benedict RH, Cookfair D, Gavett R, Gunther M, Munschauer F, Garg N, Weinstock-Guttman B (2006) Validity of the minimal assessment of cognitive function in multiple sclerosis (MACFIMS). J Int Neuropsychol Soc 12(4):549–558

Benedict RH, Cox D, Thompson LL, Foley F, Weinstock-Guttman B, Munschauer F (2004) Reliable screening for neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 10(6):675–678. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458504ms1098oa

Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33(11):1444–1452

Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, Anten B, Ekman M, Jongen PJ, Polman C, Uitdehaag B (2006) Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ 7(Suppl 2):S55–S64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-006-0378-6

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Nagels G, D'Hooghe BD, Duquet W, Duportail M, Ketelaer P (2003) Assessing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Dutch modified fatigue impact scale. Acta Neurol Belg 103(4):185–191

Diamond A (2013) Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64(1):135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Caceres F, Vanotti S, Benedict RH, Group RW (2014) Cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders among multiple sclerosis patients from Latin America: results of the RELACCEM study. Mult Scler Relat Disord 3(3):335–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2013.10.007

Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, LaRocca N, Hudson LD, Rudick R (2017) Validity of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 23(5):721–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517690821

Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH (2001) The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System: examiner’s manual. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Strober L, Chiaravalloti N, Moore N, DeLuca J (2014) Unemployment in multiple sclerosis (MS): utility of the MS functional composite and cognitive testing. Mult Scler 20(1):112–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513488235

van der Hiele K, van Gorp D, Ruimschotel R, Kamminga N, Visser L, Middelkoop H (2015) Work participation and executive abilities in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 10(6):e0129228. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129228

Dusankova JB, Kalincik T, Havrdova E, Benedict RH (2012) Cross cultural validation of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS) and the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS). Clin Neuropsychol 26(7):1186–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2012.725101

Benedict RH, Rodgers JD, Emmert N, Kininger R, Weinstock-Guttman B (2014) Negative work events and accommodations in employed multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler 20(1):116–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513494492

Wood B, van der Mei I, Ponsonby A-L, Pittas F, Quinn S, Dwyer T, Lucas R, Taylor B (2013) Prevalence and concurrence of anxiety, depression and fatigue over time in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 19(2):217–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512450351

Braley TJ, Chervin RD (2010) Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep 33(8):1061–1067

Messmer Uccelli M, Specchia C, Battaglia MA, Miller DM (2009) Factors that influence the employment status of people with multiple sclerosis: a multi-national study. J Neurol 256(12):7–1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-5225-0

Sokolov AA, Grivaz P, Bove R (2018) Cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis: recent advances in treatment and neurorehabilitation. Curr Treat Options Neurol 20(12):53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-018-0538-x

Wickström A, Dahle C, Vrethem M, Svenningsson A (2014) Reduced sick leave in multiple sclerosis after one year of natalizumab treatment. A prospective ad hoc analysis of the TYNERGY trial. Mult Scler J 20(8):1095–1101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513517590

Dijk FJHv, Dormolen Mv, Kompier MAJ, Meijman TF (1990) Herwaardering model belasting-belastbaarheid (Reevaluation of the model of workload and work capacity). Tijdschr Soc Gezondheidsz (68):3–10

Soer R, van der Schans CP, Geertzen JH, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S, Dijkstra PU, Reneman MF (2009) Normative values for a functional capacity evaluation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90(10):1785–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.05.008

Acknowledgements

We thank the neurologists, MS (research) nurses, psychologists and other healthcare professionals involved with data acquisition.

Funding

This work was financially supported by ZonMw (TOP Grant, project number: 842003003), the Dutch National Multiple Sclerosis Foundation and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DvG: study conception and design, data acquisition and analysis, study coordination, wrote manuscript. KvdH: study conception and design, data acquisition, study coordination, wrote manuscript. JvdK, MR and HM study conception and design. MH and PJ data acquisition.

LV: study conception and design, data acquisition, study coordination.

The other co-authors in the MS@Work study group (EA, EB, JvE, SF, KdG, EH, JM, WV and DZ) were involved with the acquisition of data and local study coordination. All authors read, commented on the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The MS@Work study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee Brabant (NL43098.008.12 1307; date of approval: 12-02-2014) and the Board of Directors of the participating MS outpatient clinics. All subjects provided written informed consent. The study was performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki [17].

Conflict of interest

MH, HM, JvdK, MR, EB and KdG have nothing to disclose. DvG received honoraria for presentation from Sanofi Genzyme. KvdH received honoraria for consultancies, presentations and advisory boards from Sanofi Genzyme and Merck. PJ received honoraria from Bayer, Merck and Teva for contributions to symposia as a speaker or for educational or consultancy activities. EA received honoraria for lectures and honoraria for advisory boards from Teva, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen and Novartis. JvE received honoraria for lectures and honoraria for advisory boards from Teva, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, Roche and Novartis. SF received honoraria for lectures, grants for research and advisory boards from Teva, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen, Novartis and Roche. EH received honoraria for lectures, travel grants and honoraria for advisory boards from Novartis, Teva, Roche, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme, Biogen and Bayer. JM received personal fees from Novartis, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme and Teva. WV received honoraria for lectures from Biogen and Merck, reimbursement for hospitality from Biogen, Teva, Sanofi Genzyme and Merck, and honoraria for advisory boards from Merck. DZ received honoraria for advisory boards from Novartis, Merck, Sanofi Genzyme and Biogen. LV received honoraria for lectures, grants for research and honoraria for advisory boards from Sanofi Genzyme, Merck, Novartis and Teva.

Disclaimer

The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, report writing or decision to submit the article for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 67 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Gorp, D.A., van der Hiele, K., Heerings, M.A. et al. Cognitive functioning as a predictor of employment status in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 2-year longitudinal study. Neurol Sci 40, 2555–2564 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03999-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-019-03999-w