Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) penta-graphene (PG) with unique properties that can even outperform graphene is attracting extensive attention because of its promising application in nanoelectronics. Herein, we investigate the electronic and transport properties of monolayer PG with typical small gas molecules, such as CO, CO2, NH3, NO and NO2, to explore the sensing capabilities of this monolayer by using first-principles and non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) calculations. The optimal position and mode of adsorbed molecules are determined, and the important role of charge transfer in adsorption stability and the influence of chemical bond formation on the electronic structure of the adsorption system are explored. It is demonstrated that monolayer PG is most preferred for the NOx (x = 1, 2) molecules with suitable adsorption strength and apparent charge transfer. Moreover, the current−voltage (I−V) curves of PG display a tremendous reduction of 88% (90%) in current after NO2 (NO) adsorption. The superior sensing performance of PG rivals or even surpasses that of other 2D materials such as graphene and phosphorene. Such ultrahigh sensitivity and selectivity to nitrogen oxides make PG a superior gas sensor that promises wide-ranging applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials consisting of single- or few-layer planar crystals [1], such as graphene and phosphorene, are emerging as a new paradigm in the physics of materials and have attracted increasing attention because of their unique structures and physicochemical properties [2,3,4,5], which are related to large specific surface area and fully exposed active site [6,7,8]. These properties endow 2D materials with very exciting prospects for wide potential applications in the fields of nanoelectronics, sensors, catalysis and solar energy conversion devices [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Penta-graphene (PG), a new 2D allotrope of carbon based on Cairo pentagonal tiling pattern, is a material with individual atomic layer exclusively consisting of pentagons (a mixture of sp2- and sp3-coordinated carbon atoms) in a planar sheet geometry [17]. Unlike graphene with zero bandgap, which greatly hinders its applications, PG has a quasi-direct intrinsic band gap of ∼ 3.25 eV, which can be tuned by doping [18, 19], hydrogenation [19] and electric field [20]. Because of its unusual atomic structure, PG has significant energetic, dynamic, thermal and mechanical stabilities up to 1000 K [17, 21, 22]. Thanks to its naturally existing bandgap and robust stability, PG may offer highly desirable properties and great potential for nanoelectronics, sensors and catalysis [23,24,25]. One example is that a PG-based all-carbon heterostructure shows the tunable Schottky barrier by electrostatic gating or nitrogen doping [26], verifying its potential application in nanoelectronics. Interestingly, the energy barrier of the Eley–Rideal mechanism for low-temperature CO oxidation on PG is only − 0.65 eV [25] (even comparable to many noble metal catalysts), which can be reduced to − 0.11 and − 0.35 eV by doping B and B/N, respectively [24], hence convincingly demonstrating that PG is a potential metal-free and low-cost catalyst. Recent studies also found that PG nanosheets show highly selective adsorption of NO [27], and doping can improve the adsorption of gas molecules, such as H2 [18], CO and CO2 [28] on PG. The adsorption ability of gas molecules, like graphene with good sensor properties demonstrated by both theoretical and experimental investigations [29, 30], indicates that PG would have gas-sensing properties because its electrical resistivity will be influenced by the gas molecule adsorption. However, to our best knowledge, there have been no previous reports focused on the effect of molecule adsorption on the electronic properties of PG, and given the distinctive electronic properties of PG, it is highly desirable to explore the possibility of a PG-based gas sensor.

Herein, the potential of PG monolayer as the gas sensor has been explored using density functional theory (DFT) and non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) calculations. We first investigate the adsorption behaviours of several typical molecules COx (x = 1, 2), NH3 and NOx (x = 1, 2) on PG. The preferred adsorption of NOx on PG monolayer with the appropriate adsorption strength indicates the high selectivity of PG toward gaseous NOx. The dramatic variation in current−voltage (I−V) relation before and after NO2 adsorption suggests the excellent sensitivity of PG. Both the sensitivity and selectivity for gas molecules make PG a promising candidate for high-performance sensing applications.

Methods

We perform structural relaxation and electronic calculations using first-principle calculations based on the DFT as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [31, 32]. The exchange-correlation interaction is treated within the generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional [33]. The PG model is periodic in the xy plane and separated by at least 15 Å along the z-direction. The energy cutoff is set to 450 eV and a 9 × 9 × 1 Monkhorst−Pack grid (9 × 3 × 9 for TRANSIESTA) is used for Brillouin zone integration for a 3 × 3 supercell. In order to get more accurate adsorption energy, DFT-D2 method is used. The force convergence criterion is less than 0.03 eV/Å. Spin polarization is included in the calculations of the adsorption of NOx because they are paramagnetic. The transport properties are studied by the non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) method as implemented in the TRANSIESTA package [34]. The electric current through the contact region is calculated using the Landauer−Buttiker formula [35], \( I\left({V}_b\right)={G}_0\;{\int}_{\mu_L}^{\mu_R}T\;\left(E,{V}_b\right) dE \), where G0 and T are the quantum conductance unit and the transmission rate of electrons incident at energy E under a potential bias Vb, respectively. The electrochemical potential difference between the two electrodes is eVb = μL − μR.

Results and Discussion

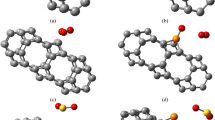

Before investigating the structural characteristics and energetics of an adsorption system, we first optimize the lattice constants of the monolayer PG and obtain a = b = 3.63 Å, in agreement with previous reported values [17]. To find the most favourable configurations, different adsorption sites and orientations are examined to adsorb gas molecules, each of them being placed on a 3 × 3 supercell PG. After full relaxation, we find that the NOx molecules chemically adsorb on PG via strong chemical bonds, whereas the other three molecules (COx, NH3) are physically adsorbed (Fig. 1). The CO, CO2 and NH3 molecules are staying above PG with an adsorption distance of 2.40, 2.73 and 2.43 Å, respectively (Table 1), showing a weak van der Waals interaction between them. By contrast, the dipolar NOx molecule is attracted to the top position of a C atom, forming a chemical bond with bond length to be 1.43~1.56 Å. Note that for PG/NO2, both N and O atoms can chemically be bonded to C atom in PG (Fig. 1e).

Adsorption configurations. a–d Side view (top) and top view (bottom) of the fully relaxed structural models of penta-graphene (PG) with CO, CO2, NH3 and NO adsorption, respectively. The last one (e) is the side view of the two bonding modes when NO2 is adsorbed, the binding energy (Ea) has been given. The distance between the gas molecule and the penta-graphene layer is indicated in a and the bond lengths between C and N (d, e) and C and O (e) at the interface are given (in angstrom units). For simplicity, these structural models are abbreviated as a PG/CO, b PG/CO2, c PG/NH3, d PG/NO and e PG/NO2

The stability of molecules on PG is evaluated by the adsorption energy (Ea), defined as Ea = Epg + gas − Egas − Epg where Epg + gas, Epg and Egas are the total energies of gas-absorbed PG, pristine PG and isolated molecule, respectively. Table 2 shows that similar to graphene and phosphorene in their potential use as gas sensors [29, 36], the adsorption energies of PG/NO and PG/NO2 are − 0.44 eV and − 0.75 eV per molecule, respectively (approaching − 0.5 eV, which is taken as the reference for gas capture), which are big enough to withstand the thermal disturbance at room temperature that is at the energy scale of kBT (kB is the Boltzmann constant) [36]. However, the adsorption energies of PG/COx and PG/NH3 are small (− 0.05 to approximately − 0.11 eV), indicating that the COx and NH3 molecules cannot readily be adsorbed on PG. The results verify that monolayer PG has a high selectivity to toxic NOx gas. More importantly, the sensing characteristics of PG for NOx is unique compared to other 2D nanosheets, such as graphene, silicene, germanene, phosphorene and MoS2, which they fail to distinguish NOx and/or COx (NH3), as shown in Table 2.

It has been demonstrated that in most cases, gas adsorption plays an important role of charge transfer in determining the adsorption energy and causing a change in the resistance of the host layer. We first calculate the interfacial charge transfer, which can be visualized in a very intuitive way, by the 3D charge density difference, Δρ = ρtot (r) − ρpg(r) − ρgas(r), where ρtot(r),ρpg(r) and ρgas(r) are the charge densities of PG with and without gas adsorption and free gas molecule in the same configuration, respectively [43]. Figure 2 shows the calculated electron transfer for the adsorption of NOx, COx and NH3 on PG, respectively. Obviously, the charge density variation is significant at the interface. Compared to the chemically adsorbed NOx systems, the charge redistribution at the PG/CO and PG/CO2 interfaces is relatively weak. This is due to the stronger interaction between covalent bonds than van der Waals forces. As for NH3 adsorption on PG, the charge redistribution occurs around the NH3 molecule.

Charge density difference plots. The adsorption configurations and charge transfer for each case in a different order from Fig. 1 are plotted in a–e. The yellow isosurface indicates an electron gain, while the blue one represents an electron loss. The unit of isosurface value is e Å−3. Apparently, electron transfer in covalent a PG/NO and b PG/NO2 structure are much more obvious than others

A further charge analysis based on the Bader method can give a more quantitative measure of charge redistribution in these systems, which are listed in Table 1. As expected, for the physical adsorption of COx and NH3 on PG, only a small amount (< 0.025 e) of charge is transferred between PG and gas molecules, further illuminating a weak binding. By contrast, the amount of charge transfer in the chemically adsorbed systems is more than 10 times higher: up to 0.517 e (0.243 e) is transferred from the PG layer to the NO2 (NO) molecule (Table 1), in agreement with their stronger adsorption energy. This systematic trend in adsorption strength correlated with the charge transfer helps us to understand the mechanism for gas molecule adsorption on PG and also indicates that the gas adsorption can be controlled by an electric field, similar to the case of gas NOx (x = 1, 2) molecules absorbed on monolayer MoS2 [9].

We next investigate the effects of gas adsorption on the electronic properties of PG. Figure 3 displays the total density of states (DOS) of PG without and with the gas molecule adsorption, as well as the projected DOS from corresponding individuals. A bandgap of 2.10 eV is obtained, in agreement with previous DFT results of pure PG [44], due to the fact that the PBE/GGA functional usually underestimate the band gap of semiconductors. Although this will affect the threshold bias (i.e. the voltage that can produce observable current), it is expected to not affect other transport properties, as will be demonstrated in the following. Figure 3a shows the DOS of pristine PG and Fig. 3b and c shows that the DOS near the valence band (VB) or conduction band (CB) of PG is not obviously affected by the COx adsorption, in perfect line with their small adsorption energies and the weak charge redistribution. Although the adsorption of NH3 molecule leads to a small state near the VB top (Fig. 3d), the physical adsorptions of molecules do not alter noticeable variations of the DOS near the Fermi level. These results indicate that the adsorption of COx and NH3 does not have a significant effect on the electronic structure of PG. By striking contrast, distinct hybridizing states are observable near the Fermi level for NOx-adsorbed PG sheet, as plotted in Fig. 3e and f. This feature, combining with major charge density redistributions, demonstrates a stronger interaction between NOx and PG monolayer, resulting into appreciable band structure modifications. This will have a great impact on the transport properties of PG, making it a very sensitive gas sensor.

Studies have demonstrated that some 2D materials are extremely sensitive to gas molecule adsorption, which corresponds to extremely low densities of gas molecules. In order to simulate the gas concentration-dependent sensitivity of PG, we calculated the effect of coverage of adsorbed gas on the properties of PG. Take the PG/NO system as an example, when the coverage is 5.56%, the adsorption energy is about − 0.44 eV per molecule. As the coverage decreases to 3.13~2.0%, the adsorption energy is reduced to about − 0.32 eV per molecule. This indicates that the gas concentration variation does not change the main conclusions. In the following calculations, therefore, the PG/NO system model with 5.56% coverage (using the 3 × 3 supercell) is chosen as a representative to calculate electronic and transport properties.

To qualitatively evaluate the sensitivity of PG monolayer for NOx monitoring, we employ the NEGF method to simulate the transport transmission and current–voltage (I–V) relations before and after the NOx adsorption using the two-probe models, as plotted in Fig. 4 a. To make the physical picture clearer and also reduce the burden of calculations, a two-probe system (pseudo “device” structure) is used, in which the “fake electrodes” just built from the periodic extension of the clean nanosheet, just as widely used in previous works [36]. Here, a 3 × 3 PG supercell (the same as the electronic calculations) without and with gas adsorption is used for each of the left and right electrodes, and the center scattering region, respectively (Fig. 4a). For comparison, the same calculations for the center scattering region without gas adsorption is performed. The calculated I−V curves of PG with and without the NOx adsorption are shown in Fig. 4b1 and 4c1. The adsorption of paramagnetic molecule NOx on PG induces spin polarization, thus leading to spin-polarized current. When a bias voltage is applied, the Fermi level of the left shifts upward with respect to that of the right electrode. Therefore, the current starts to flow only after the VB maximum of the left electrode reaches the CB minimum of the right electrode [36]. As a result, there is no current passing through the center scattering region when the bias voltage is smaller than 3.25 V, which is close to the intrinsic gap of PG [17]. When the bias voltage increases from 3.25 V, the currents in both spin channels increase rapidly. Under a bias of 3.9 V, the current passing through the PG without gas adsorption is 13.4 μA; however, as PG absorbs NO2 molecule, the current under the same bias is sharply decreased to 1.6 μA, which is about an 88% reduction. Moreover, when PG absorbs NO molecule, the current is decreased to 1.34 μA, which is about a 90% reduction. To explore the coverage effect, we further consider one molecule adsorbed on the 4 × 4 and 5 × 5, as displayed in Additional file 1: Figure S1. One can see that the interaction between molecules and the PG sheet does not change much with coverage, resulting in similar adsorption energy Ea. The transport properties of PG/NO with a 5 × 5 supercell central region is calculated and given in Additional file 1: Figure S2. Under the bias of 3.9 V, the current through a 5 × 5 supercell central region with one NO molecule is decreased to 2.87 μA (about a 79% reduction). The dramatic reduction of current indicates a significant increase of resistance after the NOx adsorption, which could be directly measured in experiment. The significant change in current signifies the ultrahigh sensitivity of the PG sensor to NOx, which rivals or even surpasses that of other 2D nanosheets such as silicene and phosphorene [36, 38], as clearly displayed in Table 2.

Illustration of the two-probe systems (a) where semi-infinite left and right electrode regions (red shaded region) are in contact with the central scattering region. For the electrodes and scatter regions, 3 × 3 supercells without and with NO are used, respectively. In b1 and c1, we display the I−V curves of pure PG and PG with the NO and NO2 adsorption. The transmission spectra under zero bias are shown in c1 and c2

To elucidate the mechanism of the increased resistance of NOx-adsorbed PG, the transmission spectra of PG with NO2 adsorption under zero bias are calculated and displayed in Fig. 4 c. One can see that a region of zero transmission with a width of 3.25 V is observed around the Fermi level, and beyond this region, there are mountain-like characteristics in the transmission spectra. The same trend of DOS (Fig. 3f) proves that the choice of PBE functional does not have a huge impact on the electronic structure and transport properties. Figure 3f shows that the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) state and highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) state are located at the gap edge, which is mainly formed by the pz orbitals. As the charge transfers from the C pz orbitals to the NO2 molecule, the LUMO and HOMO states can be obviously affected by NO2 adsorption. This indicates that the adsorbed NO2 molecule becomes strong scattering centers for charge carriers, thus resulting into a degraded mobility due to the local state around the zone center induced by NO2 molecule. In other words, the obstructed conducting channels lead to a shorter carrier lifetime or mean free path and thus a smaller mobility in NOx-adsorbed PG.

As one of the important factors for gas sensor, the recovery time is worthy to consider, which is the time taken by the sensor to get back 80% of the original resistance. According to the transition state theory [45], the recovery time τ can be calculated by the formulaτ = ω‐1 exp(E∗/KBT), where ω is attempt frequency (~1013 s−1 according to previous report [46, 47]), T is temperature and KB is Boltzmann constant (8.318 × 10-3 kJ/(mol*K)), the KBTis about 0.026 eV at room temperature, E* is the desorption energy barrier. One can see that the recovery time is closely related to the desorption barrier: the lower the desorption barrier, the shorter the recovery time of NOx on PG surface at the same temperature. Given that desorption could be considered as the inverse process of adsorption, it is reasonable to assume that the value of Ead to be the potential barrier (E∗). Thus, the potential barriers (E∗) for PG/NO and PG/NO2 are 0.44 eV and 0.75 eV, respectively. The calculated response times of the two systems are respectively 2.24 × 10−6 s and 0.34 s at the temperature of 300 K, indicating that the PG sensor is able to completely recover to its initial states. From the results given above, one can conclude that the PG is a potential material for NOx gas with a high sensitivity and quick recovery time.

Conclusions

In this work, we have systematically investigated the structural, electronic, and transport properties of the PG monolayer with the adsorption of typical gas molecules using DFT calculations. The results show that PG monolayer is one of the most preferred monolayer for toxic NOx gases with suitable adsorption strength compared to other 2D materials such as silicene and phosphorene. The electronic resistance of PG displays a dramatic increase with the adsorption of NO2, thereby signifying its ultrahigh sensitivity. In a word, PG has superior sensing performance for NOx gas with a high sensitivity and quick recovery time. Such unique features manifest the monolayer PG a desirable candidate as a superior gas sensor.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article, and further information about the data and materials could be made available to the interested party under a motivated request addressed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- 2D:

-

Two-dimensional

- CB:

-

Conduction band

- DFT:

-

Density functional theory

- GGA:

-

Generalized-gradient approximation

- HOMO:

-

Highest occupied molecular orbital

- LUMO:

-

Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

- NEGF:

-

Non-equilibrium Green’s function

- PBE:

-

Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof

- PG:

-

Penta-graphene

- PG/CO:

-

Penta-graphene with CO adsorption

- PG/CO2 :

-

Penta-graphene with CO2 adsorption

- PG/NH3 :

-

Penta-graphene with NH3 adsorption

- PG/NO:

-

Penta-graphene with NO adsorption

- PG/NO2 :

-

Penta-graphene with NO2 adsorption

- VASP:

-

Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package

- VB:

-

Valence band

References

Novoselov KS, Jiang D, Schedin F, Booth TJ, Khotkevich VV, Morozov SV, Geim AK (2005) Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:10451–10453

Butler SZ, Hollen SM, Cao LY, Cui Y, Gupta JA, Gutierrez HR, Heinz TF, Hong SS, Huang JX, Ismach AF (2013) Progress, challenges, and opportunities in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano 7:2898–2926

Neto AHC, Guinea F, Peres NMR, Novoselov KS, Geim AK (2009) The electronic properties of graphene. Rev Mod Phys 81:109–162

Reich ES (2014) Phosphorene excites materials scientists. Nature 506:19

Kistanov AA, Cai YQ, Zhou K, Dmitriev SV, Zhang YW (2016) Large electronic anisotropy and enhanced chemical activity of highly rippled phosphorene. J Phys Chem C 120:6876–6884

Kistanov AA, Cai YQ, Zhou K, Dmitrievc EV, Zhang YW (2018) Effects of graphene/BN encapsulation, surface functionalization and molecular adsorption on the electronic properties of layered InSe: a first-principles study. Phys Chem Chem Phys 20:12939–12947

Xu MS, Liang T, Shi MM, Chen HZ (2013) Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem Rev 113:3766–3798

Miro P, Audiffred M, Heine T (2014) An atlas of two-dimensional materials. Chem Soc Rev 43:6537–6554

Qu Y, Shao Z, Chang S, Li J (2013) Adsorption of gas molecules on monolayer MoS2 and effect of applied electric field. Nanoscale Res Lett 8:425

Ehenmann RC, Krstic PS, Dadras J, Kent PRC, Jakowski J (2012) Detection of hydrogen using graphene. Nanoscale Res Lett 7:1–14

Suvansinpan N, Hussain F, Zhang G, Chiu CH, Cai Y, Zhang YW (2016) Substitutionally doped phosphorene: electronic properties and gas sensing. Nanotech. 27:065708

Yang K, Huang WQ, Hu W, Huang GF, Wen S (2017) Interfacial interaction in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide/metal oxide heterostructures and its effects on electronic and optical properties: the case of MX2/CeO2. Appl Phys Express 10:011201

Cai YQ, Ke QQ, Zhang G, Zhang YW (2015) Energetics, charge transfer and magnetism of small molecules physisorbed on phosphorene. J Phys Chem C 119:3102–3110

Li L, Yu Y, Ye GJ, Ge Q, Ou X, Wu H, Feng D, Chen XH, Zhang Y (2014) Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat Nanotechnol 9:372–377

Dai J, Zeng XC (2014) Bilayer phosphorene: effect of stacking order on bandgap and its potential applications in thin-film solar cells. J Phys Chem Lett 5:1289–1293

Schwierz F (2010) Graphene transistors. Nat Nanotechnol 5:487–496

Zhang S, Zhou J, Wang Q, Chen X, Kawazoe Y, Jena P (2015) Penta-graphene: a new carbon allotrope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:2372–2377

Enriquez GJI, Villagracia ARC (2016) Hydrogen adsorption on pristine, defected, and 3d-block transition metal-doped penta-graphene. Int J Hydrogen Energy 41:12157–12166

Quijano-Briones JJ, Fernandez-Escamilla HN, Tlahuice-Flores A (2016) Doped penta-graphene and hydrogenation of its related structures: a structural and electronic DFT-D study. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18:15505–15509

Wang J, Wang Z, Zhang RJ, Zheng YX, Chen LY, Wang SY, Tsoo CC, Huang HJ, Su WS (2018) A first-principles study of the electrically tunable band gap in few-layer penta-graphene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20:18110–18116

Liu H, Qin G, Lin Y, Hu M (2016) Disparate strain dependent thermal conductivity of two-dimensional penta-structures. Nano Lett 16:3831–3842

Wu X, Varshney V, Lee J, Zhang T, Wohlwend JL, Roy AK, Luo T (2016) hydrogenation of penta-graphene leads to unexpected large improvement in thermal conductivity. Nano Lett. 16:3925–3935

Chen Q, Cheng MQ, Yang K, Huang WQ, Hu W, Huang GF (2018) Dispersive and covalent interactions in all-carbon heterostructures consisting of penta-graphene and fullerene: topological effect. J Phys D: Appl Phys 51:305301

Krishnan R, Wu SY, Chen HT (2018) Catalytic CO oxidation on B-doped and BN co-doped penta-graphene: a computational study. Phys Chem Chem Phys 20:26414–26421

Krishnan R, Su WS, Chen HT (2017) A new carbon allotrope: penta-graphene as a metal-free catalyst for CO oxidation. Carbon 114:465–472

Guo Y, Wang FQ, Wang Q (2017) An all-carbon vdW heterojunction composed of penta-graphene and graphene: tuning the Schottky barrier by electrostatic gating or nitrogen doping. Appl Phys Lett 111:073503

Qin H, Feng C, Luan X, Yang D (2018) First-principles investigation of adsorption behaviors of small molecules on penta-graphene. Nanoscale Res Lett 13:264

Zhang CP, Li B, Shao ZG (2019) First-principle investigation of CO and CO2 adsorption on Fe-doped penta-graphene. Appl Surf Sci 469:641–646

Schedin F, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Hill EW, Blake P, Katsnelson MI (2007) Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on grapheme. Nat. Mater 6:652–655

Leenaerts O, Partoens B, Peeters FM (2008) Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: a first-principles study. Phys Rev B 77:125416

Kresse G, Furthmuller J (1996) Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys Rev B: Condens Matter 54:11169–11186

Kresse G, Furthmuller J (1996) Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp Mater Sci. 6:15–50

Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M (1996) Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 77:3865–3868

Brandbyge M, Mozos JL, Ordejón P, Taylor K, Stokbro J (2002) Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys Rev B 65:16504

Buttiker M (1986) Four-terminal phase-coherent conductance. Phys Rev Lett 57:1761–1764

Kou LZ, Frauenheim T, Chen C (2014) Phosphorene as a superior gas sensor: selective adsorption and distinct I-V response. J Phys Chem Lett. 5:2675–2681

Liu Y, Wilcox J (2011) CO2 Adsorption on carbon models of organic constituents of gas shale and coal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:809–814

Feng JW, Liu YJ, Wang H, Zhao J, Cai Q, Wang X (2014) Gas adsorption on silicene: a theoretical study. Comput Mater Sci. 87:218–226

Xia W, Hu W, Li Z, Yang J (2014) A first-principles study of gas adsorption on germanene. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 16(4):22495–22498

Liu B, Zhou K (2019) Recent progress on graphene-analogous 2D nanomaterials: properties, modeling and applications. Prog Mater Sci 100:99–169

Shokri A, Salami N (2016) Gas sensor based on MoS2 monolayer. Sens Actuators B 236:378–385

Cho B, Hahm MG, Choi M, Yoon J, Kim AR, Lee YJ, Park SG, Kwon JD, Kim CS, Song M (2015) Charge-transfer-based Gas Sensing Using Atomic-layer MoS2. Sci Rep 5:8052

Si Y, Wu H-Y, Yang H-M, Huang W-Q, Yang K, Peng P, Huang G-F (2016) Dramatically enhanced visible light response of monolayer ZrS2 via non-covalent modification by double-ring tubular B20 cluster. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11:495

Einollahzadeh H, Dariani RS, Fazeli SM (2016) Computing the band structure and energy gap of penta-graphene by using DFT and G0W0 approximations. Solid State Commun. 229:1–4

Zhang YH, Chen YB, Zhou KG, Liu CH, Zeng J, Zhang HL, Peng Y (2009) Improving gas sensing properties of graphene by introducing dopants and defects: a first-principles study. Nanotechnology 20:185504

Kokalj A (2013) Formation and structure of inhibitive molecular film of imidazole on iron surface. Corros Sci. 68:195–203

Weigelt S, Busse C, Bombis C, Knudsen MM, Gothelf KV, Strunskus T, Woll C, Dahlbom M, Hammer B, Laegsgaard E, Besenbacher F, Linderoth TR (2007) Covalent interlinking of an aldehyde and an amine on a Au (1 1 1) surface in ultrahigh vacuum. Angew Chem-Int Ed. 46:9227–9230

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WQH and GFH proposed the work and revised the paper. CMQ and CQ conducted the calculations and wrote the manuscript. All authors have devoted valuable discussions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional File

Additional file 1:

Figure S1 (a-c) Side (top) and top (bottom) views of the fully relaxed structural PG/NO models of different supercells (from 3×3 to 5×5). The binding energy (Ea) is denoted. Figure S2 (a) Illustration of the two-probe systems where semi-infinite left and right electrode regions (red shade region) are in contact with the central scattering region. For the electrodes and scatter regions, 3 × 3 supercells without NO and 5 × 3 supercells with NO are used, respectively. In (b) we display the I−V curves of pure PG and PG with the NO adsorption. (DOCX 281 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, MQ., Chen, Q., Yang, K. et al. Penta-Graphene as a Potential Gas Sensor for NOx Detection. Nanoscale Res Lett 14, 306 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-019-3142-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-019-3142-4