Abstract

Purpose

Artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverage consumptions have both been reported to be associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) risk. The aim of the current study was to investigate the potential underlying associations with dynamic pancreatic β-cell function (BCF) and insulin sensitivity.

Methods

We evaluated cross-sectional associations in 2240 individuals (mean ± SD age 59.6 ± 8.18, 49.4% male, 21.9% T2D) participating in a diabetes-enriched population-based cohort. Artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks and juice consumption were assessed by a food-frequency questionnaire. Glucose metabolism status, insulin sensitivity, and BCF were measured by a seven-point oral glucose tolerance test. Regression analyses were performed to assess associations of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with measures of glucose homeostasis. Associations were adjusted for potential confounders, and additionally with and without total energy intake and BMI, as these variables could be mediators.

Results

Moderate consumption of artificially sweetened soft drink was associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity [standardized beta (95% CI), − 0.06 (− 0.11, − 0.02)], total insulin secretion [β − 0.06 (− 0.10, − 0.02)], and with lower β-cell rate sensitivity [odds ratio (95% CI), 1.29 (1.03, 1.62)] compared to abstainers. Daily artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity [β − 0.05 (− 0.09, 0.00)], and total insulin secretion [β − 0.05 − 0.09, − 0.01)] compared to abstainers.

Conclusions

Moderate and daily consumption of artificially sweetened soft drinks was associated with lower BCF, but not with insulin sensitivity. No evidence was found for associations of sugar-sweetened soft drink and juice consumption with BCF or insulin sensitivity in this middle-aged population. Prospective studies are warranted to further investigate the associations of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with non-fasting insulin sensitivity and multiple BCF aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The epidemic rise in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is partly caused by unhealthy dietary habits, including the consumption of free sugars [1]. A major source of free sugars is sugar-sweetened beverages [1, 2]. A recent meta-analysis [3] showed that sugar-sweetened beverage consumption was associated with a higher risk of T2D (RR 1.21, 95% confidence interval 1.12–1.31, n = 10 studies) per 250 g/day increase of sugar-sweetened beverage. Furthermore, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption has been positively associated with prediabetes [4] and inversely with insulin sensitivity in observational studies [4,5,6,7].

Artificially sweetened beverages have been marketed successfully as a healthy alternative for sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, aimed at controlling body weight and glucose homeostasis [8]. However, results of the previously mentioned meta-analysis [9] revealed that artificially sweetened beverage consumption is associated with an increased risk of T2D with a relative risk of 1.25 (95% confidence interval 1.18–1.33) per serving/day without, and 1.08 (1.02–1.15) after adjustment for adiposity, based on data of ten prospective cohorts [9].

The results of prospective studies varied from nonsignificant to positive associations of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with prediabetes [6, 10] and insulin resistance [5, 6, 10]. Only one study focused on the association of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with BCF (HOMA-β) and showed an inverse association with BCF in lean individuals only [6].

Despite the fact that BCF and insulin sensitivity provide important insights into the ethology of T2D, only a few studies [4,5,6] have focussed on the association of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with BCF and insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, these few studies mainly investigated BCF or insulin sensitivity based on fasting conditions, while oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)-based measures physiologically reflect the insulin secretory response of pancreatic beta cells to oral glucose ingestion [11,12,13]. Therefore, the aim of the current cross-sectional study (n = 2240) was to investigate the associations of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juice, and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with OGTT-based measures of BCF and insulin sensitivity as primary outcomes and with prediabetes and T2D as secondary outcomes.

Methods

The Maastricht Study design and population

We used data from the Maastricht Study, an observational prospective population-based cohort study. The rationale and methodology have been described previously [14]. In brief, the study focuses on the etiology, pathophysiology, complications, and comorbidities of T2D and is characterized by an extensive phenotyping approach. Eligible for participation was all individuals aged between 40 and 75 years and living in the southern part of The Netherlands. Participants were recruited through mass media campaigns and from the municipal registries and the regional Diabetes Patient Registry via mailings. Recruitment was stratified according to known T2D status, with an oversampling of individuals with T2D, for reasons of efficiency. The study has been approved by the institutional medical ethical committee (NL31329.068.10) and the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sports of The Netherlands (Permit 131088-105234-PG). All participants gave written informed consent.

The present report includes cross-sectional data from the first 3451 participants, who completed the baseline survey between November 2010 and September 2013. The examinations of each participant were performed within a time window of 3 months [14]. For the present analyses, we excluded individuals who had another type diabetes than type 2 (n = 41), used insulin (n = 220), suffered from cancer (n = 189), had not filled out a food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (n = 185) or had reported implausible total energy intake (< 800 or > 4200 kcal/day for men and < 500 or > 3500 kcal/day for women, n = 56) [15]. Finally, complete case analyses were performed; therefore, participants with a missing fasting or 120 min post glucose load blood sample, overall less than 5 OGTT blood sampling points (n = 250), or with missing values in covariates (n = 326) were excluded. This resulted in a study population of 2240 individuals for the outcome measures BCF and insulin sensitivity. For the analyses with prediabetes as an outcome, individuals with T2D were additionally excluded (n = 475). For the analyses with newly diagnosed T2D as an outcome, we excluded individuals who were previously diagnosed with T2D (n = 384). This resulted in a study population of 1765 and 1856 individuals for the outcome measures prediabetes and newly diagnosed T2D, respectively.

Data collection

Glucose metabolism

To determine glucose metabolism status, all participants, except those who used insulin, underwent a standardized 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after an overnight fast, venous blood samples were collected before, and 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after oral glucose load.

Glucose metabolism status was defined according to the WHO 2006 criteria (9): NGM (fasting plasma glucose < 6.1 mmol/l and 2 h post-load plasma glucose < 7.8 mmol/l), prediabetes (fasting plasma glucose levels of 6.1–6.9 mmol/l and/or 2 h post-load glucose levels of 7.8–11.1 mmol/l) and T2DM (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/l and/or 2 h post-load glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/l) [16]. In the present study, individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance were combined into one category—that is, prediabetes. In case individuals were on diabetes medication but did not have type 1 diabetes they were classified as having T2D [14].

Plasma for the assessment of insulin and C-peptide levels was collected in EDTA tubes, stored on ice, separated after centrifugation (3000×g for 15 min at 4 °C), and stored at − 80 °C until the assays were performed. The time between collection and storage was < 2 h. Insulin and C-peptide were measured in never-thawed plasma by use of a custom duplex array of MesoScale Discovery (MesoScale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, http://www.mesoscale.com). In short, 96 well-plates, with capture antibodies against insulin and C-peptide patterned on distinct spots in the same well, were supplied by the manufacturer. Samples (10 µl/well), detection antibodies and read buffer for electrochemiluminescence were applied according to manufacturer’s instruction and plates were read using a SECTOR® 2400 Imager. Detection ranges of the assay were 35–25,000 pg/ml for insulin and 70–50,000 pg/ml for C-peptide. Interassay coefficients of variation for insulin and C-peptide were 10.1% and 8.2%, respectively. Insulin and C-peptide values were converted from pg/ml to pmol/l using a molar mass of 5808 g for insulin and 3010 g for C-peptide.

Plasma for the assessment of glucose was collected in NaF/KOx tubes on ice. Fasting and 120-min-post-load plasma glucose were measured in fresh samples with the enzymatic hexokinase method by use of two automatic analysers (i.e., the Beckman Synchron LX20 (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA) for samples obtained between November 2010 and April 2012, and the Roche Cobas 8000 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for samples obtained thereafter). Plasma for the assessment of glucose at other time points during the OGTT was separated after centrifugation (3000×g for 15 min at 4 °C), and stored within 2 h at − 80 °C until the assays were performed. Glucose was measured in these never-thawed samples with the enzymatic hexokinase method by use of the Roche Cobas 6000 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The Pearson correlation coefficient between fresh and frozen samples were 0.96 and 0.99, respectively, for fasting and 120-min-post-load plasma glucose samples (n = 486 samples).

β-Cell function and insulin sensitivity

As β-cell function consists of multiple components, it cannot be described by a single measure. Therefore, we used three mathematical model-based parameters (β-cell glucose sensitivity, potentiation factor ratio, and β-cell rate sensitivity) according to a previously described model [17], and two classic, relatively simple β-cell function indices (C-peptidogenic index and the ratio of the C-peptide to glucose area under the curve) [17,18,19,20]. These dynamic measures of BCF were included in the analyses, because they reflect both basal and post-load insulin secretory responses [11,12,13].

The mathematical model parameter ‘β-cell glucose sensitivity’ is the slope of the glucose–insulin secretion dose–response function [17], and represents the dependence of insulin secretion on absolute glucose concentration at any time point during the OGTT. β-Cell glucose sensitivity is a sensitive index to quantify β-cell dysfunction [21,22,23]. The dose–response relationship is modulated by β-cell potentiation, which accounts for higher insulin secretion during the descending phase of hyperglycemia than during the ascending phase of an OGTT, for the same glucose concentration. β-Cell potentiation is set as a positive function of time and averages 1 during the OGTT. Therefore, it represents the relative potentiation of the insulin secretion response to glucose. The β-cell potentiation parameter used in the present analysis represents the ratio of the β-cell potentiation factor at the end of the 2-h OGTT relative to the β-cell potentiation factor at the start. ‘β-Cell rate sensitivity’ is a marker of early phase insulin release, and represents the dynamic dependence of insulin secretion on the rate of change in glucose concentration [17].

The simple β-cell function indices C-peptidogenic index (ΔCP30/ΔG30) and the ratio of the C-peptide to glucose area under the curve (CPAUC/GAUC) were also calculated. The C-peptidogenic index (the equivalent of the insulinogenic index) reflects early phase insulin secretion and has good discriminatory ability to predict (pre)T2D (ROC AUCs ≥ 78%) [18]. The CPAUC/GAUC is a measure of overall insulin secretion.

The Matsuda index (10,000/√G0 × I0 × mean G × mean I) was used as a measure of insulin sensitivity [24].

Dietary intake

All participants completed a validated 253-item food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [25] prior to being informed about their glucose metabolism status (e.g., normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes or T2D). Briefly, for each food item, frequency of consumption (ranging from ‘never or less than once a month’ to ‘every day’) and consumed amount were asked. Based on the FFQ data, daily intake of 23 main food product groups and nutrients were calculated using the Dutch Food Composition Database (NEVO) 2011 [26].

The FFQ was validated against a mean of 2.8 (range 1–5) 24-h recalls in 135 participants [25]. The correlation coefficient (95% CI) for beverage intake was 0.49 (0.44–0.76), and the FFQ ranked > 70% of the subjects correctly according to the beverage intake as compared to 24-h recalls [25].

The present study investigated consumption of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juices, and total sugar-sweetened beverages, which were appraised by 20 items: artificially sweetened soft drink combines the information collected on consumption of artificially sweetened (non)carbonated lemonades and diluted syrups (2 items). Sugar-sweetened soft drinks incorporate sugar-sweetened (non)carbonated lemonades and diluted syrups (2 items). Juice combines the information collected on consumption of 100% or sugar-sweetened fruit and vegetable juices (5 items). Finally, total sugar-sweetened beverage combines sugar-sweetened soft drink, juices, nectars, energy drinks, sports drinks, and non-alcoholic beer (11 items). One serving is equivalent to 250 ml.

Anthropometric and other measurements

Body height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured to the nearest 1 cm and 0∙5 kg with the participants wearing light clothing and no shoes (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kilogram per meter squared (kg/m2). Blood pressure, and blood lipid profiles, including triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, were determined as described previously [14]. Finally, smoking status (never, former, or current smoker), current medication use and history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer (yes/no) were self-reported. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (number of minutes/day with a step frequency > 110 step/min (~ 3.0 METs)) was measured using an activPAL3™ physical activity monitor (PAL Technologies, Glasgow, UK), as described elsewhere [27]. Detailed information concerning these measurements can be found in the study protocol of the Maastricht Study [14].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the software package SPSS Statistics version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Characteristics of the study population were described as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables or as number and proportions of participants per category for categorical variables (% of study population). Differences across glucose metabolism groups were tested by the Kruskal–Wallis test. The Matsuda index was log-transformed to obtain normally distributed data.

Linear regression analyses were performed to assess associations of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juice, and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with β-cell function indices (glucose sensitivity, potentiation factor ratio, C-peptidogenic index and overall insulin secretion) and insulin sensitivity measured by the Matsuda index, as continuous dependent variables. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the associations of the beverages with β-cell rate sensitivity, prediabetes, and T2D. β-Cell rate sensitivity was analyzed in tertiles (of which the highest tertile was considered the reference category), as the distribution of β-cell rate sensitivity was positively skewed and could not be normalized by transformations. Associations were presented as standardized regression coefficients [standardized betas (95% CI)] for continuous outcome measures and presented as odds ratios [OR (95% CI)] for categorical outcome measures.

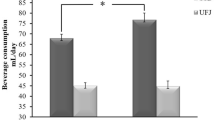

Consumption of the beverages was analyzed categorically, comparing non-consumers with moderate (more than 1 consumption a month, less than daily consumption) and daily consumers.

To adjust for potential confounding, covariates were included in the regression models if their introduction in the model changed the regression coefficient of beverage consumption by > 10%. Furthermore, to assess β-cell function relative to the degree of insulin sensitivity, the Matsuda index was included as a covariate in all regression models with a β-cell function index as the dependent variable. Model 1 (crude model) was adjusted for sex and age. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for education level (low, middle, high), mean arterial blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, lipid-modifying medication, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides and intake of fibre, trans fat, red meat, and fruit. Furthermore, beverages were mutually adjusted. In our dataset, smoking status, CVD, family history of T2D, and the intake of saturated fat, alcohol, coffee, tea, dairy, vegetables, and sweets did not confound the associations of the individual mono- and disaccharides intake with β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, prediabetes and T2D and were, therefore, not included as covariates. The adjustments for total energy intake and BMI were performed in separate models (model 3 + total energy intake; and the fully adjusted model 4 + total energy intake + BMI) as both variables can act as confounders or as mediators in the associations of beverage consumption with glucose metabolism [28]. Whether or not BMI or total energy intake were confounders or mediators was investigated by use of the SPSS macro ‘PROCESS’ provided by Preacher and Hayes [29] in additional analyses.

Results

Population characteristics

Of the 2240 participants included in this study, 1420 (61.9%) individuals had normal glucose tolerance (NGT), 345 (15.6%) had prediabetes, 91 (3.9%) were newly diagnosed with T2D, and 384 (18.5%) were previously diagnosed with T2D (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 59.5 (8.13) years and 50.4% were male.

Of the participants excluded from analyses (n = 885, see “Methods” section for reasons), mean (SD) age was 59.9 (8.60) years and 53% were male; these characteristics were essentially the same as the current study population. The proportion of individuals previously diagnosed with T2DM was higher than in the current population, which is mainly due to the use of insulin treatment (n = 220) and according to protocol no OGTT could be performed.

The prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and history of CVD was lowest among NGT individuals and highest among T2D individuals. Previously diagnosed T2D persons had the highest HDL:LDL ratio, most likely due to lipid-modifying medication. Indices for BCF and insulin sensitivity were highest among NGT individuals (representing good BCF and insulin sensitivity) and lowest among T2D individuals (representing impaired BCF and insulin resistance). Moreover, self-reported artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was lowest in the NGT group and highest in previously diagnosed T2D persons. Total juice consumption was highest in the NGT group and lowest in the previously diagnosed T2D persons. Sugar-sweetened soft drink and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption were comparable between the glucose metabolism groups (Table 1). Overall, the consumption of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverages was relatively low. The median beverage intake of the moderate and daily consumers groups are shown in Table 2.

Daily consumers of artificially sweetened soft drinks and non-consumers of juice were more often previously diagnosed with T2D and less often normoglycemic. Furthermore, daily sugar-sweetened soft drink consumers, and moderate and daily artificially sweetened soft drink consumers had higher prevalence of overweight/obesity compared to the non-consumer groups (data not shown).

Associations of artificially sweetened soft drink consumption with BCF and insulin sensitivity

Both moderate and daily vs. no artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was significantly associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity, β-cell potentiation, total insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity (as measured by the Matsuda index) (Table 3) and β-cell rate sensitivity (Table 4) in the crude model.

In the fully adjusted model, artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was significantly associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity, with beta (95% CI) of − 0.06 (− 0.11, − 0.02) for moderate consumption, and − 0.05 (− 0.09, − 0.00) for daily consumption, respectively. Similar associations were observed between artificially sweetened soft drink consumption and lower overall insulin secretion, with beta (95% CI) of − 0.06 (− 0.10, − 0.02) for moderate consumption, and of − 0.05 (− 0.09, − 0.01) for daily consumption, respectively (Table 3). Moderate, but not daily consumption, was associated with β-cell rate sensitivity compared to abstainers, with OR (95% CI) of 1.29 (1.03, 1.62) (Table 4). No associations were observed for artificially sweetened soft drink consumption with prediabetes and diabetes (see Online Appendix Tables 1 and 2).

Associations remained essentially the same after exclusion of participants who were previously diagnosed with T2DM.

Associations of sugar-sweetened soft drink, juice and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with BCF and insulin sensitivity

Moderate compared to abstainers of total sugar-sweetened drink consumption was associated with higher β-cell glucose sensitivity, higher overall insulin secretion and higher insulin sensitivity in the crude models (Table 3). None of the associations remained significant after further adjustments.

No significant associations were observed for moderate and daily consumption compared with no consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drink (Tables 3, 4; Online Appendix Tables 1 and 2).

Associations remained essentially the same after exclusion of participants who were previously diagnosed with T2DM.

Additional analyses

We additionally investigated whether total energy intake and BMI acted as confounders, effect modifiers or mediators in the association of beverage consumption with glucose metabolism. Total energy intake and BMI did not act as main confounders, as the associations remained essentially the same after additional adjustments for total energy intake and BMI (see Online Appendix Tables 3 and 4).

Furthermore, having a normal weight, overweight or obesity did not significantly modify the associations. Finally, mediation analyses revealed no mediating effects of total energy intake nor of BMI in the associations of beverage consumption with BCF (data not shown).

Discussion

The novelty of this study is the evaluation of the associations of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drink, juice and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with multiple dynamic indices of pancreatic BCF and insulin sensitivity. After adjustment for confounders, artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity, overall insulin secretion, and β-cell rate sensitivity. No associations were observed for the consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juices and total sugar-sweetened beverages with BCF, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism status.

In our analyses, artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with lower β-cell glucose sensitivity, β-cell rate sensitivity, and overall insulin secretion. These findings are in line with one previous observational study that showed an association of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with a lower fasting BCF and lower insulin sensitivity in lean participants (BMI < 25 kg/m2) only [6], but not with three other observational studies who did not show an association with insulin sensitivity [4, 5, 7]. These discrepant findings may be caused by differences in research methodology, i.e., three studies focused on fasting insulin sensitivity only [4,5,6] and two studies excluded newly diagnosed T2D from analyses [5, 7]. In addition, however, randomized controlled trials so far have not been able to detect any effects of artificial sweeteners on glucose metabolism [30, 31]. Therefore, future studies are necessary to confirm our results.

In a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies [9], all except one study showed that a higher artificially sweetened beverage consumption was significantly [9, 28, 32,33,34,35,36] or weakly (nonsignificant) associated [37, 38] with higher T2D risk in analyses without adjustment for adiposity. After additional adjustment for adiposity, associations were attenuated towards the null in four of these studies [9, 28, 32, 34]. In line with these studies, high consumption of artificially sweetened soft drinks was positively, but non-significantly, associated with prediabetes and T2D in the present study. The observed associations of higher artificially sweetened soft drink consumption with lower BCF indicate an association between higher artificially sweetened soft drink consumption and impaired glucose homeostasis. However, the range of exposure to artificially sweetened soft drink consumption varied from 0 to 300 g/day (percentiles 5–95) in the current study population, and this range might be too small to detect significant associations with prediabetes and T2D because of loss in information when using binary outcome measures.

The mechanisms by which artificially sweetened beverage consumption may modify glucose homeostasis are not fully understood. One suggested mechanism is that artificially sweeteners alter gut microbiota resulting in impaired glucose homeostasis [6, 39, 40]. Other studies suggest that artificially sweeteners increase the hedonistic desire for sweet taste [33, 41], an overestimation of beverage calories saved by consuming non-caloric instead of caloric beverages [33, 34], and/or increased appetite [4], which all might result in a higher total energy intake and weight gain, and subsequently a higher risk of disturbed glucose homeostasis. However, mediation analyses in the present data suggest that an increase in energy intake and BMI is not the main pathway by which artificially sweetened soft drink consumption causes impaired glucose homeostasis. Others argue that the observed association is mainly caused by reversed causality [32, 42, 43]. This hypothesis implies that persons started to consume artificially sweetened beverages in an attempt to lose weight or to better control glucose homeostasis after being diagnosed with T2D. However, sensitivity analyses in another study [36] and the present study indicate that reverse causality might not explain the association of a higher consumption of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with a higher risk of disturbed glucose homeostasis. As in our study, the associations of artificially sweetened soft drink consumption with BCF remained significant after exclusion of participants who were previously diagnosed with T2D. Moreover, BMI did not modify the association between artificially sweetened soft drink consumption and measures of glucose homeostasis.

The absence of an association of total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and sugar-sweetened soft drinks with measures of glucose homeostasis are in line with studies focusing on T2D as an outcome [7, 30, 33, 44], but in contrast with others who found that higher consumption of total sugar-sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks was positively associated with T2D [28, 34, 37, 45]. In one study [37] the positive association attenuated towards the null after adjustment for BMI though. Studies that focused on fasting measures of insulin sensitivity even showed an inverse association with total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption [4, 5, 7]. These conflicting findings could be partly due to differences in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages between study populations (which was relatively low in ours), or in beverages included in the sugar-sweetened beverage category [7, 9]. In addition, fasting (static) measures of insulin sensitivity are less reliable than dynamic indices of insulin sensitivity [46].

In our study, we did not observe associations of juice consumption with β-cell function, insulin sensitivity or glucose metabolism status. A recent meta-analysis [47] showed that 100% juices were not associated with T2D, whereas sugar-sweetened juices were positively associated with T2D [47]. As our data did not allow dissecting between consumption of 100% juices and sugar-sweetened fruit- and vegetable-based juices, no conclusions regarding the association of juices with BCF and insulin sensitivity can be drawn.

One of the strengths of our study is that β-cell dysfunction and lower insulin sensitivity provide physiological information on early abnormalities in glucose metabolism that eventually result in prediabetes and T2D. Furthermore, as beta-cell function is a continuous outcome measure it has a larger statistical power to detect associations compared to the dichotomous outcome measure T2D. Another strength is the use of multiple indices to assess various dynamic aspects of BCF and insulin sensitivity indices which better reflect metabolic conditions. In addition, the large sample size and the inclusion of participants covering the total glucose metabolism spectrum from NGT to T2D, and the extensive data collection on demographics and lifestyle factors, allowed a thorough adjustment for confounders. One limitation is the cross-sectional design of our study, by which causality could not be determined. Furthermore, there is a risk of reporting/information bias; however, as all participants completed the FFQ prior to being informed about their glucose metabolism status, we consider the risk of reporting bias is minimal. Finally, the degree of variation in consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juice and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption may have been somewhat low to estimate associations with measures of glucose homeostasis.

Conclusions

In the current study, artificially sweetened soft drink consumption was associated with lower BCF. We found no evidence for associations of sugar-sweetened soft drinks, juices and total sugar-sweetened beverages with BCF, insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism status. This is the first study on the association of artificially and sugar-sweetened soft drink, juice and total sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with non-fasting insulin sensitivity and multiple BCF aspects. Therefore, prospective studies are warranted to confirm current findings and further investigate the role of ASB and SSB in observational and clinical settings.

References

World Health Organization (2016) Global report on diabetes. World Health Organization, Geneva

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB (2010) Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 33(11):2477–2483. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1079

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G, Lampousi A-M, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, Schwedhelm C, Bechthold A, Schlesinger S, Boeing H (2017) Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol 32(5):363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0246-y

Ma J, McKeown NM, Hwang SJ, Hoffmann U, Jacques PF, Fox CS (2016) Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption is associated with change of visceral adipose tissue over 6 years of follow-up. Circulation 133(4):370–377. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.115.018704

Lana A, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E (2014) Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is positively related to insulin resistance and higher plasma leptin concentrations in men and nonoverweight women. J Nutr 144(7):1099–1105

Yarmolinsky J, Duncan BB (2016) Artificially sweetened beverage consumption is positively associated with newly diagnosed diabetes in normal-weight but not in overweight or obese Brazilian adults. J Nutr 146(2):290–297. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.220194

Yoshida M, McKeown NM, Rogers G, Meigs JB, Saltzman E, D’Agostino R, Jacques PF (2007) Surrogate markers of insulin resistance are associated with consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and fruit juice in middle and older-aged adults. J Nutr 137(9):2121–2127

Gardner C, Wylie-Rosett J, Gidding SS, Steffen LM, Johnson RK, Reader D, Lichtenstein AH (2012) Nonnutritive sweeteners: current use and health perspectives: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 35(8):1798–1808. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-9002

Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, Forouhi NG (2015) Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ 351:h3576. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3576

Ma J, Jacques PF, Meigs JB, Fox CS, Rogers GT, Smith CE, Hruby A, Saltzman E, McKeown NM (2016) Sugar-sweetened beverage but not diet soda consumption is positively associated with progression of insulin resistance and prediabetes. J Nutr 146(12):2544–2550. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.116.234047

Cersosimo E, Solis-Herrera C, Trautmann ME, Malloy J, Triplitt CL (2014) Assessment of pancreatic beta-cell function: review of methods and clinical applications. Curr Diabetes Rev 10(1):2–42

Cobelli C, Toffolo GM, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, Denti P, Caumo A, Butler P, Rizza R (2007) Assessment of β-cell function in humans, simultaneously with insulin sensitivity and hepatic extraction, from intravenous and oral glucose tests. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293(1):E1–E15

Mari A, Ferrannini E (2008) β-Cell function assessment from modelling of oral tests: an effective approach. Diabetes Obes Metab 10(s4):77–87

Schram MT, Sep SJ, van der Kallen CJ, Dagnelie PC, Koster A, Schaper N, Henry RM, Stehouwer CD (2014) The Maastricht Study: an extensive phenotyping study on determinants of type 2 diabetes, its complications and its comorbidities. Eur J Epidemiol 29(6):439–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9889-0

Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH (1997) Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 65(4 Suppl):1220S–1228S (discussion 1229S–1231S)

World Health Organization (2006) Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia: report of a WH. World Health Organization, Geneva

Mari A, Schmitz O, Gastaldelli A, Oestergaard T, Nyholm B, Ferrannini E (2002) Meal and oral glucose tests for assessment of beta-cell function: modeling analysis in normal subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283(6):E1159–E1166. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00093.2002

den Biggelaar LJ, Sep SJ, Eussen SJ, Mari A, Ferrannini E, van Greevenbroek MM, van der Kallen CJ, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD, Dagnelie PC (2016) Discriminatory ability of simple OGTT-based beta cell function indices for prediction of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: the CODAM study. Diabetologia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4165-3

Phillips D, Clark P, Hales C, Osmond C (1994) Understanding oral glucose tolerance: comparison of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabet Med 11(3):286–292

Levine R, Haft DE (1970) Carbohydrate homeostasis. N Engl J Med 283(4):175–183

Ferrannini E, Gastaldelli A, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, Mari A, DeFronzo RA (2005) beta-Cell function in subjects spanning the range from normal glucose tolerance to overt diabetes: a new analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(1):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1133

Ferrannini E, Gastaldelli A, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, Pettiti M, Natali A, Mari A, DeFronzo RA (2003) Predominant role of reduced beta-cell sensitivity to glucose over insulin resistance in impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetologia 46(9):1211–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-003-1169-6

Ferrannini E, Mari A (2014) Beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 63(10):1217–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2014.05.012

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22(9):1462–1470

van Dongen MC, Wijckmans-Duysens NEG, den Biggelaar LJ, Ocke MC, Meijboom S, Brants HA, de Vries JH, Feskens EJ, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Geelen A, Stehouwer CD, Dagnelie PC, Eussen SJ (2019) The Maastricht FFQ: development and validation of a comprehensive food frequency questionnaire for the Maastricht study. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 62:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.10.015

Environment NIfPHat (2011) Dutch Food Composition Database. Stichting NEVO. http://www.rivm.nl/en/Topics/D/Dutch_Food_composition_Database. Accessed Jan 2016

van der Berg JD, Willems PJ, van der Velde JH, Savelberg HH, Schaper NC, Schram MT, Sep SJ, Dagnelie PC, Bosma H, Stehouwer CD, Koster A (2016) Identifying waking time in 24-h accelerometry data in adults using an automated algorithm. J Sports Sci 34(19):1867–1873. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1140908

Consortium I (2013) Consumption of sweet beverages and type 2 diabetes incidence in European adults: results from EPIC-InterAct. Diabetologia 56(7):1520–1530

Hayes AF, Preacher KJ (2014) Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br J Math Stat Psychol 67(3):451–470

Engel S, Tholstrup T, Bruun JM, Astrup A, Richelsen B, Raben A (2018) Effect of high milk and sugar-sweetened and non-caloric soft drink intake on insulin sensitivity after 6 months in overweight and obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 72(3):358

Grotz VL, Pi-Sunyer X, Porte D Jr, Roberts A, Trout JR (2017) A 12-week randomized clinical trial investigating the potential for sucralose to affect glucose homeostasis. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 88:22–33

de Koning L, Malik VS, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB (2011) Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverage consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Am J Clin Nutr 93(6):1321–1327. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.007922

Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Wang Y, Lima JA, Michos ED, Jacobs DR (2009) Diet soda intake and risk of incident metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 32(4):688–694

Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB (2004) Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 292(8):927–934. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.8.927

Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB, D’Agostino RB, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS (2007) Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation 116(5):480–488

Fagherazzi G, Vilier A, Sartorelli DS, Lajous M, Balkau B, Clavel-Chapelon F (2013) Consumption of artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages and incident type 2 diabetes in the Etude Epidémiologique auprès des femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale-European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 97(3):517–523

Palmer JR, Boggs DA, Krishnan S, Hu FB, Singer M, Rosenberg L (2008) Sugar-sweetened beverages and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American women. Arch Intern Med 168(14):1487–1492

Sakurai M, Nakamura K, Miura K, Takamura T, Yoshita K, Nagasawa S, Morikawa Y, Ishizaki M, Kido T, Naruse Y (2014) Sugar-sweetened beverage and diet soda consumption and the 7-year risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged Japanese men. Eur J Nutr 53(1):251–258

Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, Israeli D, Zmora N, Gilad S, Weinberger A (2014) Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 514(7521):181–186

Pepino MY (2015) Metabolic effects of non-nutritive sweeteners. Physiol Behav 152(Pt B):450–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.06.024

Green E, Murphy C (2012) Altered processing of sweet taste in the brain of diet soda drinkers. Physiol Behav 107(4):560–567

Bhupathiraju SN, Pan A, Malik VS, Manson JE, Willett WC, van Dam RM, Hu FB (2013) Caffeinated and caffeine-free beverages and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 97:155–166

Greenwood DC, Threapleton DE, Evans CE, Cleghorn CL, Nykjaer C, Woodhead C, Burley VJ (2014) Association between sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Nutr 112(5):725–734. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114514001329

Montonen J, Jarvinen R, Knekt P, Heliovaara M, Reunanen A (2007) Consumption of sweetened beverages and intakes of fructose and glucose predict type 2 diabetes occurrence. J Nutr 137(6):1447–1454

Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Arakawa K, Yu MC, Pereira MA (2010) Soft drink and juice consumption and risk of physician-diagnosed incident type 2 diabetes: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 171(6):701–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp452

Borai A, Livingstone C, Kaddam I, Ferns G (2011) Selection of the appropriate method for the assessment of insulin resistance. BMC Med Res Methodol 11(1):158

Xi B, Li S, Liu Z, Tian H, Yin X, Huai P, Tang W, Zhou D, Steffen LM (2014) Intake of fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9(3):e93471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093471

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all voluntary participants from The Maastricht Study as well as the funding bodies (see below).

Funding

This study was supported by the European Regional Development Fund via OP-Zuid, the Province of Limburg, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs (Grant 31O.041), Stichting De Weijerhorst (Maastricht, The Netherlands), the Pearl String Initiative Diabetes (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), the Cardiovascular Center (CVC, Maastricht, The Netherlands), CARIM School for Cardiovascular Diseases (Maastricht, The Netherlands), CAPHRI School for Public Health and Primary Care (Maastricht, The Netherlands), NUTRIM School for Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism (Maastricht, The Netherlands), Stichting Annadal (Maastricht, The Netherlands), Health Foundation Limburg (Maastricht, The Netherlands) and by unrestricted grants from Janssen-Cilag B.V. (Tilburg, The Netherlands), Novo Nordisk Farma B.V. (Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) and Sanofi-Aventis Netherlands B.V. (Gouda, The Netherlands).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJCJB contributed to the design and conception of the study, performed statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SJPME contributed to the design and conception of the study, interpretation of the data, writing and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, and assisted in the collection of dietary intake data. SJSS contributed to the design and conception of the study, interpretation of the data, and writing and critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. MCJMD, KFMD, and NW assisted in the collection of dietary intake data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AM and EF designed the mathematical model, provided support in performing mathematical analyses, contributed to the data quality of the mathematical analyses, made important contributions to the interpretation of the BCF data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MTS, CJK, AK, NS, RMAH, MMG, and CDAS contributed to the design and conception of the Maastricht Study, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and/or provided critical comments and suggestions on the manuscript, reviewed the final draft of the manuscript, and gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

den Biggelaar, L.J.C.J., Sep, S.J.S., Mari, A. et al. Association of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened soft drinks with β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and type 2 diabetes: the Maastricht Study. Eur J Nutr 59, 1717–1727 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02026-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02026-0