Abstract

Background

The present study investigated the efficacy and safety of nivolumab in pre-treated patients with advanced NSCLC harbouring KRAS mutations.

Methods

Clinical data and KRAS mutational status were analysed in patients treated with nivolumab within the Italian Expanded Access Program. Objective response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival were evaluated. Patients were monitored for adverse events using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

Results

Among 530 patients evaluated for KRAS mutations, 206 (39%) were positive while 324 (61%) were KRAS wild-type mutations. KRAS status did not influence nivolumab efficacy in terms of ORR (20% vs 17%, P = 0.39) and DCR (47% vs 41%, P = 0.23). The median PFS and OS were 4 vs 3 months (P = 0.5) and 11.2 vs 10 months (P = 0.8) in the KRAS-positive vs the KRAS-negative group. The 3-months PFS rate was significantly higher in the KRAS-positive group as compared to the KRAS-negative group (53% vs 42%, P = 0.01). The percentage of any grade and grade 3–4 AEs were 45% vs 33% (P = 0.003) and 11% vs 6% (P = 0.03) in KRAS-positive and KRAS-negative groups, respectively.

Conclusions

Nivolumab is an effective and safe treatment option for patients with previously treated, advanced non-squamous NSCLC regardless of KRAS mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The advent of immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in clinical practice1 is leading to a significant improvement of life expectancy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Modulating the antitumour immune response by targeting the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death 1 ligand (PD-L1) axis emerged as an effective and tolerable treatment in early phase I studies,2 offering the potential for durable disease control and long-term survival outcomes in heavily pre-treated NSCLC patients.3 Four randomised phase III trials have subsequently demonstrated that single-agent ICIs, nivolumab,4,5 pembrolizumab6 or atezolizumab7 significantly improved overall survival (OS) and quality of life (QoL) as compared to docetaxel in pre-treated NSCLC patients, emerging as new standard of care in second or later lines of therapy. In particular, the phase III Checkmate 057 trial5 first demonstrated a significant superiority in terms of objective response rate (ORR), OS, tolerability and QoL in favour of the anti-PD-1 nivolumab over docetaxel in pre-treated patients with non-squamous NSCLC. Importantly, nivolumab resulted superior to docetaxel irrespective of tumour PD-L1 expression, even if higher efficacy was detected among patients expressing high PD-L1 levels. Landmark survival analysis8 excluding patients with poor prognosis who died within the first 3 months of therapy, has subsequently demonstrated that patients with low or no tumour PD-L1 expression who were alive at 3 months also benefited from nivolumab. These evidences led to the final approval of nivolumab by regulatory authorities in March 2016 for the second/third-line treatment of non-squamous NSCLC regardless of tumour PD-L1 expression.9 The data emerging from both randomised trials6,7,10 and real-life experiences11,12 suggested that immunotherapy is effective in a significant subgroup of patients, leading to durable disease control, long-term survival and improved QoL. Conversely, about 50% of pre-treated patients did not gain any benefit from ICIs and a small subgroup of them developed early progression or death within 3 months of therapy.8,11,12,13,14,15 Thus, identifying predictive biomarkers of clinical response/resistance to ICIs is crucial for the selection of an appropriate candidate to immunotherapy. Looking for molecular predictors of ICI efficacy, the pre-specified subgroup analysis of the 057 trial10 clearly showed that nivolumab did not improve neither PFS nor OS in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-positive NSCLC. Similar results were obtained in trials with pembrolizumab or atezolizumab as well as in recent meta-analysis.16,17

KRAS mutations represent the most common oncogene driver detected in about 30% of non-squamous NSCLC, usually occurring at codons 12–13 and associated with cigarette smoking.18,19 Several efforts have been made by the scientific community to understand the potential role of KRAS mutations as a therapeutic target in cancer cells, but no effective KRAS-inhibitors have been approved yet for clinical use. The efficacy of nivolumab in KRAS-mutated NSCLC is not well defined. The results from clinical trials suggested that patients harbouring KRAS-mutations could result in more sensitivity to nivolumab as compared to KRAS wild-type mutations, but the small number of patients evaluated in single trials7,10 precluded any definitive conclusion. A recent meta-analysis17 investigated the predictive role of KRAS-mutations in 519 patients with previously treated NSCLC included in trials with nivolumab or atezolizumab (CheckMate 057, OAK and POPLAR studies). The results of such analysis showed a greater benefit in KRAS-mutant subgroups even if the difference was not statistically significant, likely because KRAS-mutation status was known only in a small fraction of cases. In the present study, we investigated whether nivolumab could result effective in terms of ORR, PFS and OS in pre-treated metastatic NSCLC patients harbouring KRAS mutations.

Methods

Patients

The study was conducted in patients participating in the Italian expanded access program (EAP). Patients were eligible if they aged ≥18 years, had histologically or cytologically confirmed diagnosis of non-squamous NSCLC, stage IIIB–C/IV (according to Version 8 of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) TNM Staging System), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance-status score <3, and had disease progression or recurrence after receiving at least one prior systemic therapy for advanced/metastatic disease.

Patients were excluded if they had autoimmune disease, symptomatic interstitial lung disease, systemic immunosuppression and prior treatment with immune-stimulatory antitumour agents including checkpoint-inhibitors. Patients with brain metastases were eligible if they have received prior loco-regional treatment and were stable at the time of inclusion. Tumour PD-L1 status was not required.

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol was previously approved by the Independent Ethics Committee and all the patients provided a written informed consent before enrolment.

Study design and treatment

We retrospectively collected clinical data and KRAS mutational status from patients’ charts and hospital electronic medical records for eligible patients who have been treated with nivolumab at 168 Italian cancer centres from May 2015 to December 2016. All included patients were followed until the end of data collection on September 2017.

Nivolumab was available upon physicians’ request for eligible patients through the EAP. Nivolumab 3 mg/kg was administered intravenously every 2 weeks for ≤24 months. Patients included in the analysis received ≥1 dose of nivolumab. The treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, or the completion of permitted cycles (≤24 months).

KRAS mutation testing data from tumour samples obtained before enrolment in the EAP were used where available. DNA extracted from tissue/cytological samples was subjected to KRAS mutational analysis using local practices.

Radiological evaluation of treatment efficacy by CT-scan was performed at week 12 and every 12 weeks thereafter until disease progression and responses were evaluated by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) v1.1. Patients were monitored for AEs using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0.

Statistical analysis

The main objective of the study was to assess nivolumab efficacy in terms of ORR, PFS and OS in NSCLC patients with or without KRAS mutations. Secondary endpoint was to assess whether nivolumab safety profile was different in individuals with or without KRAS mutations.

For efficacy analysis, patients were grouped according to their tumour KRAS mutational status into ‘positive’ if they harboured KRAS mutations or ‘negative’ if they did not have KRAS mutations. Patients’ clinical–pathological characteristics and associations with KRAS mutational status were examined with a descriptive analysis comparing the differences by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

Investigator-assessed efficacy outcomes, including ORR, disease control rate (DCR), median PFS and OS, were assessed in KRAS-positive vs KRAS-negative patients both in the overall population and in predefined subgroups of patients. ORR was defined as the combined rates of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR). DCR was defined as the combined rates of CR, PR and stable disease (SD). Median PFS was defined as the time between the date of inclusion and the date of disease progression determined by RECIST v1.1, death from any cause or the last follow-up. Median OS was defined as the time between the date of inclusion and the date of death. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method, providing median and P-values, with the use of the log-rank test for comparisons. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the logistic regression model when referring to binary outcome and Cox regression model when considering time to events. A P-value < 0.05 was used as a threshold for statistical significance.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics software version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

From May 2015 to December 2016, a total of 1588 non-squamous NSCLC patients were considered eligible and participated in the EAP at 168 centres in Italy. Among 530 patients evaluated for KRAS mutations, 206 (39%) resulted positive while 324 (61%) were KRAS wild-type mutations. KRAS mutation subtypes were not known in the analysed population. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-activating mutations were detected in 17/324 patients (5%), while ALK/ROS1 rearrangements were found in 7/324 (2%) of KRAS wild-type patients. As reported in Table 1, the baseline characteristics were similar between the two subgroups. However, in the KRAS-positive group, the percentage of current/former smokers was significantly higher than in the KRAS-negative group (86% vs 76%, P = 0.01), as was the percentage of patients with CNS metastasis (29% vs 20%, P = 0.01). Patients with KRAS mutations received a median of eight doses (range: 1–54), with a median follow-up of 8.0 months (range: 0.1–25.9), while KRAS-negative patients received a median of seven doses (range: 1–52), with a median follow-up of 7.4 months (range: 0.2–27.4).

KRAS mutations and tumour response

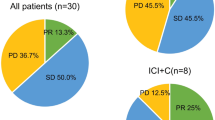

Among patients with KRAS-positive NSCLC treated with nivolumab, one patient (0.5%) experienced CR, 39 (19%) had a partial response (PR), 55 (27%) stable disease (SD) and 88 (43%) progressive disease (PD). No significant differences between KRAS-positive and KRAS-negative patients have been observed as regards both ORR (20% vs 17%, P = 0.39) and DCR (47% vs 41%, P = 0.23), as illustrated in Table 2. The results of both ORR and DCR analyses across different predefined subgroups of patients were consistent with those observed in the overall population.

KRAS mutations and patients’ survival

As illustrated in Fig. 1, at the time of survival analysis (median follow-up of 8.1 months, range: 0.1–27.4), median PFS was 4 months (95% CI: 3.6, 4.4) in the KRAS-positive group and 3 months (95% CI: 3.6–4.4) in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.56). The 3-months PFS rate was significantly higher in the KRAS-positive group as compared to the KRAS-negative group (53% vs 42%, P = 0.01). The 6-months and 12-months PFS rate was similar between the two groups. The 6-months rate of PFS was 33% in the KRAS-positive group and 31% in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.63); the 12-months rate of PFS was 19% in both the groups (P = 0.99).

There were no significant OS differences between KRAS-positive and KRAS-negative patients. The median OS was 11.2 months (95% CI: 9.3–13.1) in the KRAS-positive group and 10 months (95% CI: 9.3–13.1) in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.86, Fig. 2). The 3-months rate of OS was 84% in the KRAS-positive group and 78% in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.09); the 6-months rate of OS was 71% in the KRAS-positive group and 64% in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.09); the 12-months rate of OS was 47% in the KRAS-positive group and 46% in the KRAS-negative group (P = 0.92). The results of ORR, PFS and OS analyses across different predefined subgroups of patients were consistent with those observed in the overall population.

Safety

Treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) of any grade and grade 3–4 for KRAS-positive and KRAS-negative non-squamous NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab are shown in Table 3. The percentage of patients with TRAEs of any grade was significantly higher in the KRAS-positive group (45% vs 33%, P = 0.003) as was the percentage of patients with TRAEs of grade 3–4 (11% vs 6%, P = 0.03). The percentage of patients who discontinued treatment was 81% in KRAS-positive and 84% in KRAS-negative patients. TRAEs leading to discontinuation were hepatic, gastrointestinal and pulmonary with similar frequencies observed in the different subgroups of patients. No treatment-related deaths have been reported. The results of safety analyses across different predefined subgroups of patients were consistent with those observed in the overall population.

Multivariable analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional regression analysis was performed to assess whether KRAS mutations were independent factors related to nivolumab safety in terms of any grade and grade 3–4 toxicities. All clinical–pathological parameters found to have a P-value < 0.05 at univariate analysis were included as covariates in the multivariable model.

KRAS mutations remained significantly associated with higher toxicity rate, including both any grade AEs (OR: 1.66 (1.14–2.41) P = 0.008) and grade 3–4 AEs (OR: 2.25 (1.14–4.44) P = 0.02) (Table 4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study investigating the predictive role of KRAS mutations in advanced non-squamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab. The results of this real-world analysis demonstrated that both clinical efficacy and safety of nivolumab were comparable to those observed in the phase III randomised CheckMate 057 trial, including the same NSCLC population.5

Our results demonstrated that KRAS status is not a reliable predictor of nivolumab efficacy in terms of RR, PFS and OS. Differences in all clinical endpoints were not statistically significant, with the only exception of 3-months PFS that was significantly higher in the KRAS-positive group.

Interest in KRAS mutant NSCLC is growing because of the lack of any specific agent available in patients harbouring such molecular alteration, the high incidence in non-squamous NSCLC and the association with smoking history and therefore with tumour mutational burden, one of the most innovative predictive biomarkers to immunotherapy. Preclinical and clinical evidences suggested that KRAS-positive NSCLC seems to gain more benefit from immunotherapy. First of all, KRAS-mutant tumours are characterised by the presence of CD8 + lymphocyte infiltrates in the tumour microenvironment (TME),20 while a significant association between KRAS mutations and PD-L1 expression has been observed in lung adenocarcinoma.21,22 Coelho et al.23 have recently demonstrated that oncogenic RAS signalling upregulated tumour PD-L1 expression stabilising the PD-L1 transcript in KRAS-mutant adenocarcinoma, thus providing an additional mechanism whereby KRAS-positive tumours respond to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Recent studies demonstrated how the crosstalk between the cancer cells intrinsic RAS signalling and the TME extended beyond the tumour PD-L1 expression, regulating many other different TME components,24 such as inflammatory cells, immune T-cells and myeloid cells density, cancer-associated fibroblasts and endothelial cells properties and extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, ultimately favouring immune-escape, cancer growth and metastatic process. The possibility of using KRAS status for selecting patients potentially sensitive to immunotherapy is certainly of great interest. Indeed, this biomarker is generally included among the molecular tests performed in metastatic NSCLC, facilities are available in the majority of centres, it is relatively easy to perform and not expansive. However, it is now clear that KRAS-mutant NSCLC is a heterogeneous disease, including different tumour subtypes with variable biological background, different prognosis and clinical response to immunotherapy. A recent work25 showed that tumours with co-occurring KRAS/P53 mutations were associated with higher PD-L1 expression as well as elevated PD-L1+/CD8+ cell ratio and increased mutation burden as compared to tumours with KRAS or P53 single mutation. Interestingly, patients with KRAS+/P53+ NSCLC also showed a remarkable and durable clinical benefit from anti-PD-1 therapy, suggesting a synergistic and complementary effect of both signalling pathways to the TME immunogenicity. Conversely co-occurring inactivation of LKB1/STK11 tumour suppressor gene was associated with lack of tumour response and shorter PFS and OS as compared to LKB1/STK11 wild-type patients with KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma, suggesting LKB1-loss as a major driver of immune-escape and a genomic biomarker of innate resistance to ICIs.26 Previous reports described as the inactivation of LKB1 were associated with lower PD-L1 expression levels and paucity of infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes in the TME of KRAS-positive NSCLC,27 suggesting that normal LKB1 tumour suppressor gene plays a crucial role in maintaining a KRAS-mutant-driven immunosuppressive TME. Recent findings demonstrated that STK11/LKB1 alterations are associated with lack of response to PD-1 inhibitors efficacy, regardless of KRAS mutations or PD-L1 expression status,26,28 suggesting that different combinations of P53, STK11 and EGFR mutations were associated with different tumour microenvironments and may predict clinical response to PD-1 blockade.28 Unfortunately, neither P53 nor LKB1 status were known for KRAS-positive NSCLC patients included in our study because of the lack of tumour tissue available for molecular analysis. Since only 24/324 KRAS wild-type patients had EGFR-activating mutations or ALK/ROS1 rearrangements, we were not able to evaluate their impact on efficacy outcomes observed with nivolumab in the overall population. Further trials including larger cohorts of NSCLC patients with known KRAS, P53, STK11, EGFR and PD-L1 status are warranted.

Interestingly, our series provided new information with regard to nivolumab tolerability according to tumour KRAS-mutation status in a real-life setting. Although nivolumab was overall well tolerated, the percentage of both any grade and grade 3–4 TRAEs was significantly higher in the KRAS-positive group, suggesting a potential interaction between KRAS-signalling and treatment tolerability. The reasons for this observation remain speculative and warrant further investigation in clinical studies. However, imbalances in the clinical characteristics of patients at baseline may have influenced the different tolerability profile of nivolumab between the two treatment groups.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that KRAS mutations are not useful for selecting patients candidate to nivolumab therapy. Nivolumab is an effective and safe treatment option for patients with previously treated, advanced NSCLC regardless of KRAS-mutation status.

References

Brahmer, J. R. Harnessing the immune system for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 1021–1028 (2013).

Topalian, S. L. et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2443–2454 (2012).

Gettinger, S. et al. Five-year follow-up of nivolumab in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the CA209-003 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1675–1684 (2018).

Brahmer, J. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 123–135 (2015).

Borghaei, H. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 123–135 (2015).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387, 1540–1550 (2016).

Rittmeyer, A. et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389, 255–265 (2017).

Peters, S. et al. OA03.05 analysis of early survival in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab vs docetaxel in CheckMate 057. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, S253 (2017).

Novello, S. et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 27(suppl 5), v1–v27 (2016).

Borghaei, H. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1627–1639 (2015).

Dudnik, E. et al. Effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The real-life data. Lung Cancer (2017), Nov 23. pii: S0169 5002(17)30582-2.

Schouten, R. D., Muller, M., de Gooijer, C. J., Baas, P. & van den Heuvel, M. Real life experience with nivolumab for the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma: data from the expanded access program and routine clinical care in a tertiary cancer centre—The Netherlands Cancer Institute. Lung Cancer (2017), Nov 17. pii: S0169–5002(17)30569-X.

Shiroyama, T. et al. Pretreatment advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) for predicting early progression in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 7, 13–20 (2018).

Inoue, T. et al. Analysis of early death in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Clin. Lung Cancer (2017), Mar;19(2):e171-e176.

Taniguchi, Y. et al. Predictive factors for poor progression-free survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Anticancer Res. 37, 5857–5862 (2017).

Lee, C. K. et al. Checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer—a meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, 403–407 (2017).

Lee, C. K. et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics associated with survival among patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors for advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 4, 210–216 (2018).

Rodenhuis, S. et al. Mutational activation of the K-ras oncogene. A possible pathogenetic factor in adenocarcinoma of the lung. N. Engl. J. Med. 317, 929–935 (1987).

Slebos, R. J. et al. K-ras oncogene activation as a prognostic marker in adenocarcinoma of the lung. N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 561–565 (1990).

Toki, M. M. N. et al. Immune marker profiling and PD-L1, PD-L2 expression mechanisms across non-small cell lung cancer mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 35(15 suppl), 9076 (2017).

D’Incecco, A. et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in molecularly selected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 112, 95–102 (2015).

Chen, N. et al. KRAS mutation-induced upregulation of PD-L1 mediates immune escape in human lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 66, 1175–1187 (2017).

Coelho, M. A. et al. Oncogenic RAS signaling promotes tumor immunoresistance by stabilizing PD-L1 mRNA. Immunity 47, 1083–1099.e6 (2017).

Dias Carvalho, P. et al. KRAS oncogenic signaling extends beyond cancer cells to orchestrate the microenvironment. Cancer Res. 78, 7–14 (2018).

Dong, Z. Y. et al. Potential predictive value of TP53 and KRAS mutation status for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 3012–3024 (2017).

Skoulidis, F. et al. STK11/LKB1 mutations and PD-1 inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 8, 822–835 (2018).

Skoulidis, F. et al. Co-occurring genomic alterations define major subsets of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma with distinct biology, immune profiles, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Discov. 5, 860–877 (2015).

Biton J. et al. TP53, STK11 and EGFR Mutations Predict Tumor Immune Profile and the Response to anti-PD-1 in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 May 15. pii: clincanres. 0163.2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.C and D.G contributed to the design of the study; F.C., O.A., A.C.B., P.B., R.C., C.D., A.D., G. Finocchiaro, G. Francini, F.G., M.G., A.I., L.L., O.M., C.N., G.P., E. Ricevuto, E. Roca, D.T. and D.G. contributed to the clinical management of patients and database, providing clinical, pathological and molecular data; F.P and D.G performed data analysis and interpretation; F.P and F.C wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

F.C. was a consultant for BMS, AZ, Roche, MSD and Pfizer; D.G. was a consultant for BMS; the remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial protocol was previously approved by the Local Independent Ethics Committee and all the patients provided a written informed consent before enrolment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of data and material

All the data analysed supporting the results reported in the article may be found/ are archived at the Biostatistics Unit, Scientific Direction, IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome.

Note

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Passiglia, F., Cappuzzo, F., Alabiso, O. et al. Efficacy of nivolumab in pre-treated non-small-cell lung cancer patients harbouring KRAS mutations. Br J Cancer 120, 57–62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0234-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0234-3

This article is cited by

-

Knockdown of NCAPD3 inhibits the tumorigenesis of non-small cell lung cancer by regulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway

BMC Cancer (2024)

-

Targeting KRASG12D mutation in non-small cell lung cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential

Cancer Gene Therapy (2024)

-

The impact of oncogenic driver mutations on neoadjuvant immunotherapy outcomes in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2023)

-

RAS oncogenic activity predicts response to chemotherapy and outcome in lung adenocarcinoma

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Optimizing palliative chemotherapy for advanced invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung

BMC Cancer (2021)